Graham Page

First published in Research World June 2010

Should researchers be replacing conventional tools with neuroscience – or would that be throwing away good practices, painstaking validated over decades, in the pursuit of the newest and latest scientific toy?

Marketers are increasingly turning to neuroscience to inform their brand and advertising decisions. The result has been a blossoming of ‘neuromarketing’ agencies that deploy methods similar to those used by neuroscientists.

Millward Brown is one agency which has formed a dedicated neuroscience practice to explore new opportunities for neuroscience-based research methods. Over the last six years we have examined all the main techniques in the area and compared them to the existing qualitative and quantitative work we do. That experience suggests that there is significant value in certain neuroscience methods – but only alongside existing methods rather than as a replacement, and only if interpreted with care by people with experience in the field.

At the recent Market Research Society annual conference, Research 2010, I discussed ways in which the industry can implement neuroscience-based methods alongside more established tools. The key for practitioners is to use neuroscience only when it will add value, and when it is relevant to the client issue, rather than because it’s new or ‘sexy’. It is also important to focus on more scalable technologies, as these offer the most cost-effective route to additional insights for marketers.

Three key neuroscience approaches, which can be integrated well with existing research tools in a scale-able way, are:

- Implicit Association measurement

- Eye tracking

- Brainwave measurement

It is necessary to use a variety of methods because there is no ‘magic bullet’ – different approaches do different things so are useful at different times.

Implicit Association Measurement

While not strictly speaking a ‘neuroscience’ technique, this approach shares with more biometric methods the principle of inferring consumers’ responses rather than asking a direct question. In this case the inference comes from measuring consumers’ reaction times or accuracy on tasks which are systematically biased by their reactions to brands or ads. What this delivers in addition to established tools is an insight into the ‘raw’ ideas stirred up by brands and ads, prior to any filtering for ‘sense’ or social desirability – but which still may play a role in shaping consumers’ responses.

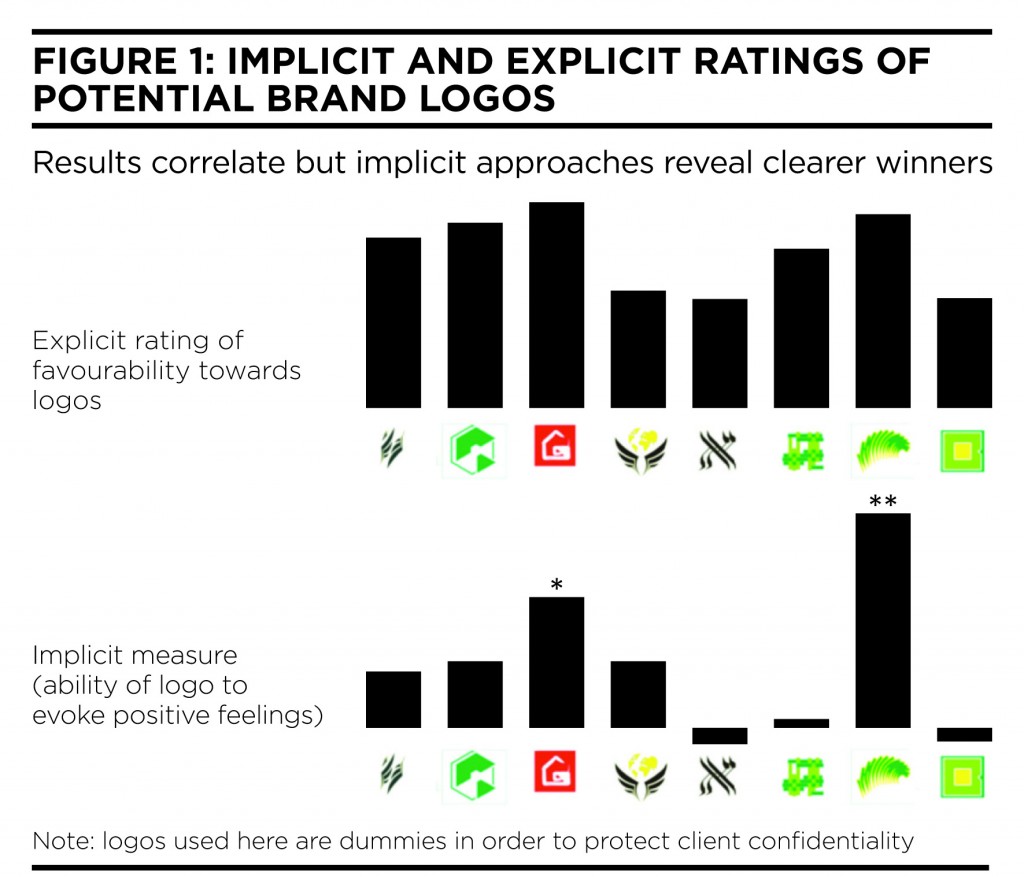

This approach can help in a number of areas, including brand positioning, ad development, logo research and product or concept evaluation. For instance, in a recent ad development project, a poor response to the main character in an ad was revealed to be driven by perceived threat, and (for actively religious viewers) perceptions of unholiness – ideas which weren’t articulated through more explicit questions. Likewise in a recent logo test, implicit measurement was able to pull out a much clearer winner (see Figure 1), suggesting that this is a useful approach for this type of research.

Eye Tracking

Eye-tracking technology is probably the most widely used by clients currently, partly because it has become greatly simplified and more accessible in cost terms in recent years. The benefits are clear – eye movements can be a good guide to the focus of visual attention, with more detail and accuracy than self report. However, the methods also say nothing about why a particular area catches the eye, or their response to it, which is why additional interviewing alongside is crucial to maximise the value. We have used this approach in a number of markets and have found it a useful additional diagnostic measure, which helps explain advertising or packaging performance as measured via survey instruments. For instance in a project for a RoC skincare ad, we found a powerful illustration of a communication barrier due to misdirected attention during a key scene. Using this information the client was able to re-edit the ad and generate a much stronger final film.

Brainwave measurement

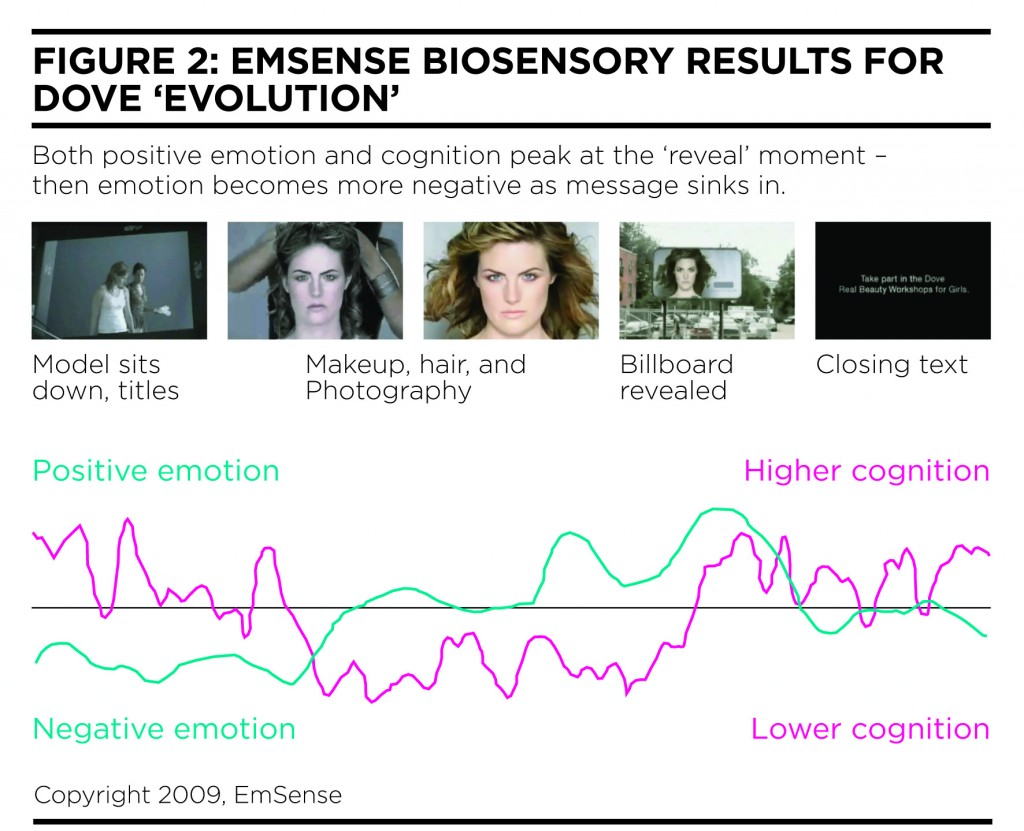

Recently we have worked with US-based Emsense to integrate EEG and other biometrics with survey tools. We have found the Emsense technology particularly useful in that it is far more scalable and cost-effective than conventional EEG methods. What the biometric data can add is a powerful diagnostic of participants’ moment-by-moment response to an ad, or a brand experience, revealing details that may happen too quickly for them to report via other means.

Figure 2 shows the results of this approach during for the well known Dove ‘Evolution’ film. In Link™ survey-based research this film is a hugely powerful performer, and the Emsense data provides a powerful illustration of the journey consumers take, and which creative elements are driving this response. While the model is being ‘made-up’, positive emotion actually rises (which is not something viewers report verbally). There is also a crescendo of both positive emotion and cognition at the moment it is revealed that this is about the making of an ad – as understanding blossoms and the cleverness of the idea is apparent. However, it is also clear that as the implications of this moment sink in, positive emotions decline as the point of the ad is considered, which is what gives the communication such power. This sort of learning can be a very powerful stimulus for creative development.

Other methods

Other approaches, such as fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging), can also give powerful insights. For instance, in a recent project conducted with the University of Bangor and the Royal Mail, we used fMRI to reveal that physical marketing materials such as direct mail evoke stronger emotional processing than identical material presented ‘virtually’ on a screen. This insight into the deepest areas of the brain is only available through such scanning technologies. However, the cost, limited sample size and timeframe of such approaches mean that it is likely the industry will only use them sparingly, and for ‘bigger’ industry issues.

When should you use neuroscience?

Neuroscience tends to add the most value under certain circumstances:

- Dealing with sensitive material. This is when Qual/survey methods are most vulnerable to distortion.

- Dealing with abstract or ‘higher order’ ideas. Implicit association measurement in particular helps get at ideas consumers may think sound strange in interview situations .

- Probing for transient responses to ads or brand experiences. Measures like EEG and eye-tracking can add value here in pinpointing the emotional or cognitive highlights and low points in a piece of creative, or the focus of attention.

- Giving more detail on consumers feelings. Neuroscience methods can add a powerful additional level of detail about the timing of emotional responses, and the elements of an ad or brand which are driving them.

Different methods lend themselves to different areas of research. Implicit association measurement is well suited to brand strategy work, product testing, concept testing and assessment of communication from marketing campaigns. Eye-tracking and brainwave measurement, on the other hand, lend themselves better to creative optimisation work, packaging and in-store research.

Getting the best out of neuroscience

My experience of researching and now using these methods has suggested the following best practices:

- Be critical. The technology can be alluring but the same questions that would be asked of any conventional research technique should be asked of these methods. Ask for proof and go along to fieldwork to see the reality of the research environment.

- Look for experience. This is a complex area, so familiarity with the approaches, and a scientific perspective is important to understand what is claim versus reality.

- Integrate. These methods do not reveal the ‘inner truth’ – they are a useful additional perspective on consumers’ responses to brands and marketing, which needs interpretation in the light of other information. It is only by combining approaches that greater insight is revealed.

The future

The future for neuromarketing could be seen as another piece of the toolkit for understanding consumers, rather than as a revolution. We will see more partnerships between conventional agencies, and neuroscience practitioners. We will also find some of the less effective neuromarketing approaches fall by the wayside as the market matures, and their validity (or otherwise) becomes more apparent. As the novelty subsides, marketers will get better at discriminating between hype and insight. Most importantly, however, it will become more apparent that real understanding comes from integrating information, rather than looking at one perspective alone, and it is in this context that these approaches will prosper.

Graham Page runs Millward Brown’s global Consumer Neuroscience practice. This article is adapted from a paper presented at the MRS Research 2010 conference in London, March 2010