SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) laid siege to the Greater China Region (mainland China, Hong Kong SAR, and Taiwan) from late March to June 2003. At the time I was managing director for TNS (Kantar) in Hong Kong, where 299 people died from the disease (versus four deaths from COVID-19 at the time of writing). We researched the effects of SARS on citizens in Greater China, and results were published by ESOMAR in 2004.

17 years on, I am now researching the effects of a similar disease, but this time it is a pandemic. In our current study, we look more closely at the causes, with results to be published by WWF and GlobeScan. In advance of our 2020 COVID-19 research, I reviewed the major findings of the SARS studies and also made a comparison with a similar COVID-19-effect study, which shows similarities, but also how the world has already changed towards on-line behaviour.

Expectations for containment – lessons learned

In January 2004, people deemed it likely that SARS would return, albeit on a much smaller scale than in 2003. The attitude was that if SARS came back, the public and governments would have learned from the first outbreak. In 2020, this was true in Greater China, South Korea and Singapore, but less so elsewhere.

In February 2003, the media began reporting on a rapidly spreading type of pneumonia. Identified as SARS, 8,098 cases were reported worldwide resulting in 774 deaths. Greater China accounted for 92% of cases and 89% of fatalities. As a point of comparison, COVID-19 has a lower mortality rate, but has spread more widely; over 425,323 cases and more than 18,943 fatalities (www.worldometers.info) have been reported, and these numbers are rising rapidly.

My first recollection of SARS was how unexpectedly it arrived. In 2003, market research was conducted face to face or via telephone, panel-based surveys did not yet exist, and Google did not yet provide immediate information. A major crisis seemed imminent and the public and governments seemed panic-stricken, but within months, SARS was under control. The second most memorable aspect was how quickly SARS abated and economic confidence returned. In contrast: the spread of COVID-19 was tracked daily since January 2020, so its arrival in many countries could have been expected. The biggest question is when it will be under control.

Immediate reaction to SARS in 2003

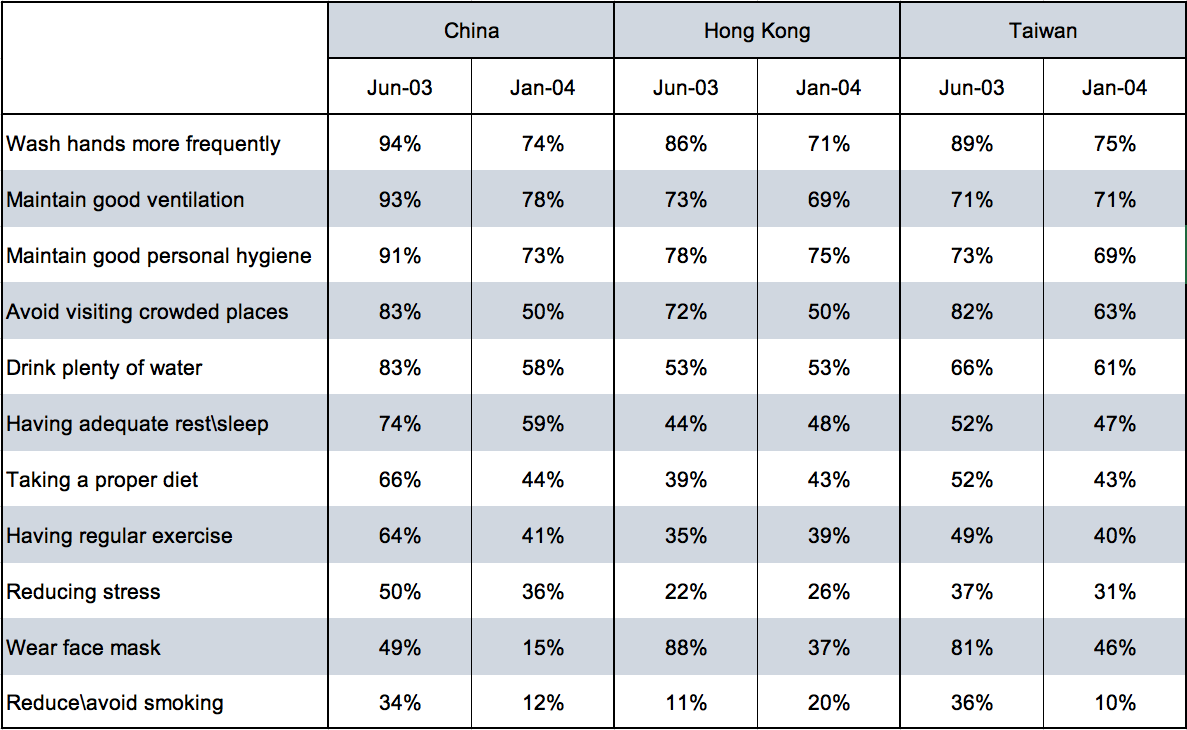

We first assessed of the impact of SARS in April 2003 and conducted further research in June 2003 and January 2004 to assess the longer-term behaviour changes.

Face masks were the main prevention measure for SARS. In April 2003, 86% of the Hong Kong population were wearing face masks: in streets, on public transport, and at work. The city seemed to be in fear of an invisible enemy. We are seeing this again in 2020, and people understood then as they do now that the threat was real. Greater China learned important lessons from SARS (see the table below) whereas the rest of the world, lacking experience with this type of illness, has been slow to cope with COVID-19.

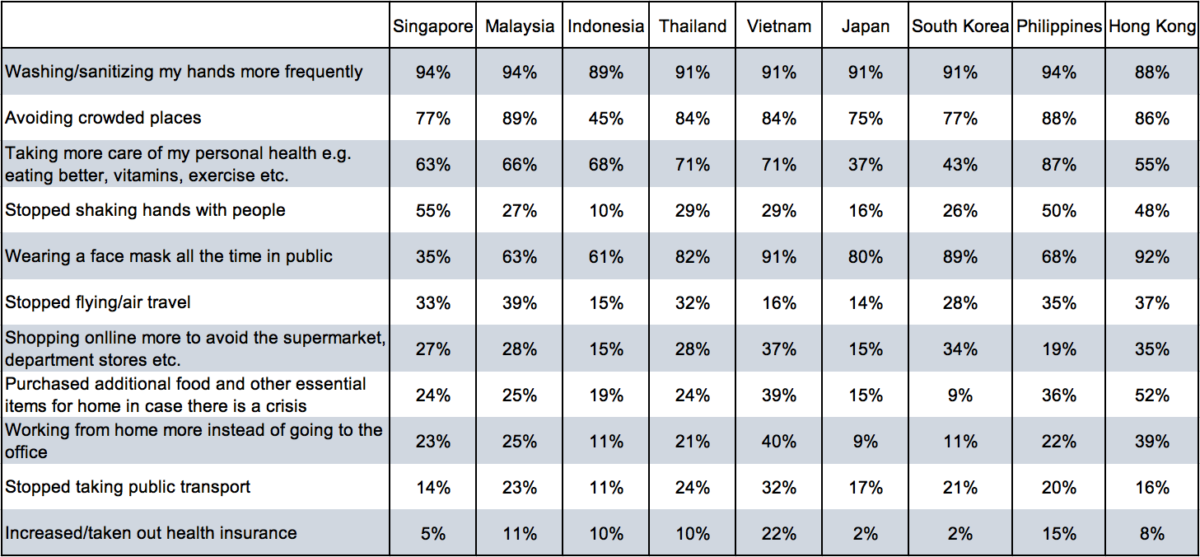

Research from Toluna in February 2020 shows similar reactions in Hong Kong to the current crisis, where 92% reported that they wear face masks, 88% washed their hands more frequently, and 55% improved their personal hygiene. The set of countries below is different from the table above, with other behaviour measured, like shaking hands, which is becoming an outdated greeting. The most fundamental changes are induced by the internet; working from home and on-line shopping – this is likely to stay once the crisis has abated.

More outbreaks: bird flu, swine flu, MERS, ebola, zika

In January 2004, it was known that SARS could be transmitted from droplets released when an infected person coughs or sneezes, but there was extensive debate about its cause. Civet cats were identified as a possible origin of SARS, resulting in a mass culling when the disease threatened to re-appear in early 2004. This culling was also undertaken with Avian Influenza A (H5N1), or Bird Flu, when a large number of poultry were destroyed in countries such as Vietnam, Japan, and China in 2004. Swine Flu and MERS appeared next, while Ebola and Zika outbreaks occurred periodically.

Looking ahead, I am borrowing from an article by Simon Evans, Director of International Partnerships in the Lord Ashcroft International Business School, in the Conversation.

Although we are still contending with the effects of COVID-19, we must look back and ahead at the causes. We know that the disease originated in the Chinese city of Wuhan, an important wildlife trade hub – both legal and illegal. The outbreak is believed to have originated in a market where animal products and meats are available, including peacocks, porcupines, bats, and rats. Some of this trade was legal under Chinese law but the co-existence of illegal trade allowed traders to introduce illicit wildlife products, making it difficult to regulate and control. As with Ebola and SARS, it appears likely that the disease was transmitted from animals to humans.

In each case, the existence of unsanitary and poorly regulated wildlife markets provided an ideal environment for diseases to cross over between species. In China, Thailand, and Vietnam, where wildlife consumption is embedded in the culture, transmission can re-occur at any time.

The Chinese government responded to the current crisis by enacting a permanent ban on such markets, effectively closing down much of its domestic wildlife trade. The Vietnamese government is considering similar measures, but the bans do not cover all forms of consumption, wildlife markets exist in many countries, and without enforcement, bans cannot have a material effect. Illegal wildlife trade was once criticised largely from a conservation perspective, but it is now being considered in relation to broader themes of public health and economic impact. There are already compelling arguments for discontinuing the trade: animals are kept in unhealthy conditions and the trade reduces their numbers in the wild. As outlined earlier; we have been here before with SARS and the wildlife trade might resume. COVID-19 clearly represents an unparalleled opportunity to combat the wildlife trade and ensure that animal-borne diseases do not mutate and cross over to humans, which is imperative to prevent a next pandemic.

1 comment

Great to monitor how this would impact our behaviour!

Tks for sharing Wander!