See Simon Chadwick commentary on this piece for more information

The COVID-19 pandemic, with no end in sight, has disproportionately impacted marginalized communities who are experiencing higher infection rates and economic devastation. Systemic inequities have also been brought to light with global protests against police brutality and racial discrimination, further demonstrating the urgent need for the data, insights, and research community to reflect on our own moral responsibility to act.

The cross-cutting and growing field of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) provides practical frameworks and principles including intersectionality and design justice, to radically improve how we do research and mitigate its impacts on the communities we study or involve. Contrary to misconceptions that DEI can make research overly complicated, it is really about ensuring that our data and insights accurately reflect the complexity of the real world.

Many of the data sets we rely on – from medical trials to crash tests to facial recognition – are either too narrow or assume a default reference point that doesn’t exist. This can result in gender and racial biases, sometimes with fatal consequences. Reflecting on the intersectional data from our daily lives makes research more inclusive, innovative, and more equitable.

Adopting an equitable approach is also about acknowledging the inherently political nature of research and knowledge creation. The data that we generate and the insights we produce directly impact decision-making, in effect, determining where resources go and how money is spent. There is no such thing as objective research: why we research, who does the research, and how we research all matter.

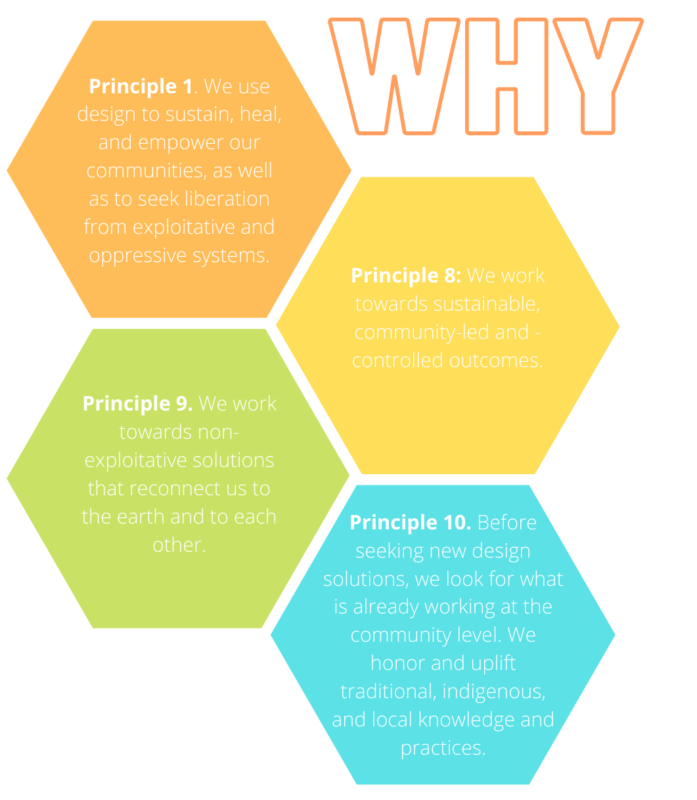

Why we research matters

The Design Justice Network is a community of individuals and organizations dedicated to rethinking design processes so that they center people who are too often marginalized by design. We can extend design justice principles to the research, data, and insights field as we engage in design processes ourselves, and along the way determine concrete actions to address discrepancies, inequities, and injustices relevant to our work.

Consider: Why are we conducting research? What is the purpose? What are the goals or intended outcomes of the study? Do we have social or environmental outcomes, to which we are committed to adhering?

Our purpose, or our why, comprises our vision and our values embedded in our research practice. It is important to ask these questions throughout the course of our research, from the stage of commissioning to design and from implementation to communications and evaluation because our vision and values will steer the course of the study.

Principle 1 asks if the study has a social and equitable mission. Is it intended to improve social outcomes and correct systemic inequities?

Principle 8 asks if the study includes a commitment to accountability to the communities being surveyed. Is it designed by community members and does it include a sustainability component?

Principle 9 asks if the study has an environmental component to not only mitigate adverse impacts but nurture positive outcomes. Does the research include a social, human rights, gender, or environmental impact assessment?

Principle 10 asks if the study includes recognition of past work on the topic with an emphasis on locally generated, indigenous knowledge, and practice. Does the research include a literature review, systematic review, interviews with local knowledge brokers, etc.?

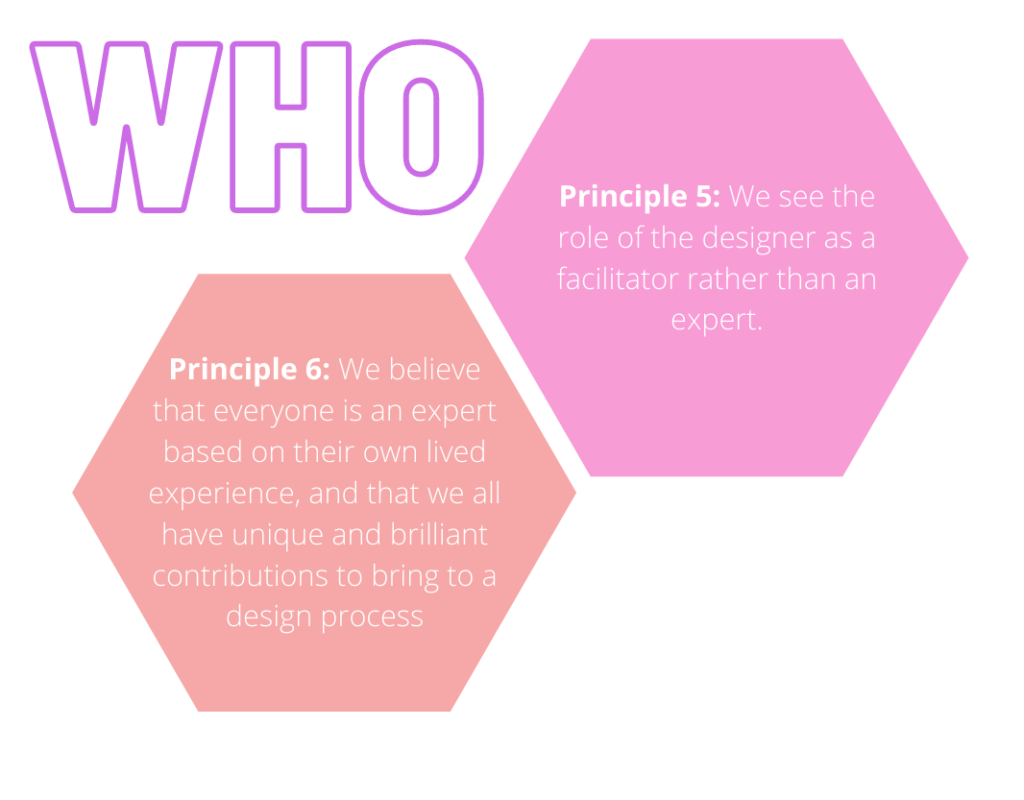

Who does research matters

It’s important to consider who is conducting the research and how they impact the work. What are the roles and responsibilities of the researcher or other team members? Is the research co-designed or co-implemented with the community in question? Are we adequately listening to and capturing all perspectives from the research team and the studied community?

Our people, or our who, comprise our actors, allies, and advocates embedded in our research practice. Asking these questions throughout the course of the research, from the stage of commissioning to design and from implementation to communications and evaluation because our teams and communities will steer the course of the study.

Principle 5 asks if the researcher approaches the study, not as an expert, but as a facilitator who does not have the full knowledge of the community in question. Does the research recognize the blind spots of the researcher and does the exercise ensure the research team’s humility throughout?

Principle 6 asks if the study places value on the contributions of the research participants or communities as experts of their own experiences. Does the research allow for co-design, adaptation, or any way for participants to contribute to the research process?

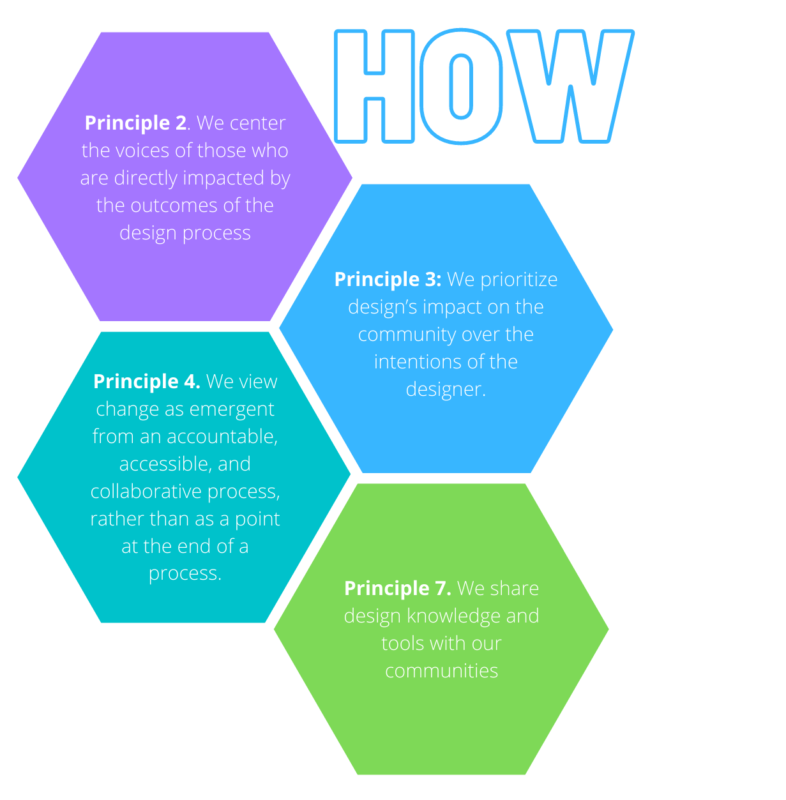

How we research matters

How are we conducting research? Reflecting on the process, and its impact can bring some realizations to steps along the way that can center the communities and participant voices who are considered the subject.

These principles guide us as researchers to consider our own intentions throughout our work and understand ownership of knowledge as something that must be shared. Research does not have to be only extractive: it can be collaborative and inclusive not just in the subject matter, but in the process of design.

Principle 2 can be seen as a reminder that research both in its process and findings can have long-term effects on participants. Is the research centering their voices? This is a key element of ensuring the design process is just and equitable.

Principle 3 asks if the research’s impacts on the community is prioritized over the research design’s intentions. Could there be unintended outcomes? What is the meaning of free, prior, and informed consent in this context?

Principle 4 asks if there is a commitment and series of actions that ensure that a research process is transparent, collaborative, and social change-oriented. Is the research process evaluated continuously and iterated for increased accessibility, accountability, and collaboration?

Principle 7 asks if there is a mechanism for training and knowledge sharing with the communities that are being studied. Does the research include a component in which we report back to the communities and ensure that it is a productive and constructive process for everyone involved?

A call to action

Are you ready to commit to change? The Design Justice principles were developed from a global, collaborative network of professionals committed to reflection and taking action to correct marginalization that is too often by design. Alongside the ESOMAR guidelines, we invite you to sign on to the principles and commit to putting these equitable principles to work!