Brandon Ellse

By now, most of us have heard the all too familiar story about behavioural economics.

All together now: “Traditional economics dictates that people act rationally based on principles such as utility maximisation, transitivity and non-satiation. However, countless studies have shown that people regularly and predictably behave contrary to these principles.” Okay, now that that’s over with, so what?

What does that really mean for market researchers? Sure, I get that people are at the core of market research and therefore we should care about any endeavours relating to this core, but how can behavioural economics practically change the market research landscape? This remains less than clear to me. We’ve all heard about the experiments, their control and treatment groups beautifully poised in anticipation of the “ta-da” moment where “real” human behaviour is revealed like a rabbit pulled from a hat. These behavioural economics-inspired tales seem to waft over our intellectual senses, leaving us with a strange feeling of certainty that only the perception of knowledge exclusivity can bring. I won’t lie, I’m impressed. Getting at causality is no mean feat and I am often left in awe of the ingenuity of these researchers, but I want practical application and I get the feeling that you do too.

The Holy Grail?

We, as market researchers, have for years marched into battle armed with our holiest of weapons, the survey. The battleground may be changing from a physical space to a digital one but the basic principles remain the same. We’re asking people questions about their behaviour, either directly or indirectly. Indirect questioning is now considered “best practice” by many, largely owing to its supposed ability to reveal unconscious preferences. Preferences are really just contextualised nuggets of truth after all, aren’t they? If we can find out these truths we can understand, and if we can understand we can predict. That sounds like the beautiful basics of science to me. So how do we fare at this truth-gauging game?

A fair question, but are we talking about absolute truth here or are there shades of grey? Well, let’s consider a typical shopper. Are a shopper’s preferences revealed and acted upon with the sort of consistency that would make Tiger Woods proud? No, obviously not with 100% consistency and probably not even with 80% consistency. I’m here to tell you that it’s worse than that – much worse. Kant, amongst others, was famous for professing that we cannot know absolute truth. Perhaps he had a point.

Point of Purchase

Research conducted by the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) has shown that between 50 and 70% of purchase decisions, at a brand level, happen at the point of purchase. If we were to start getting more specific and talk about the choice of flavours, for example, I suspect that number would approach 90%. In other words, up to 70% of the time, people are making their decisions at that moment, in that store, standing in front of that shelf. I don’t know about you, but if I were in the truth-gauging game I would take a big step back and reflect. So what’s really going on here? In the end it comes down to a bunch of cognitive heuristics concealed within a sheath of context. It’s my deep feeling that we, as researchers, are missing something here. We’re missing context. You simply cannot expect to holistically envisage human preferences without the illuminating light of context. Sure, the heuristics may provide the decisive blow, but context is the support mechanism, the environment within which the heuristics are spurred into action. Respondents reveal preferences and assign rating scores within their unique prevailing environment. What we can be sure of is that standalone revealed preferences are hollow without an understanding of context.

Contextual paradigm shift

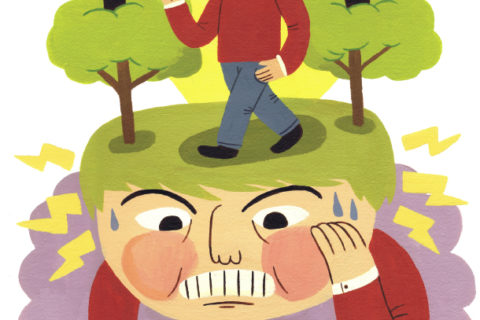

This makes sense since this is, after all, precisely how our brains interpret reality. Our brains have evolved to understand the world by making comparisons with previously formed mental categories or benchmarks. To our brains, everything is relative. Remove individuals from their environments and their behaviours become quite different. What’s more, we regularly under- oroverestimate this environmental impact. In fact, we are notoriously poor at predicting the impact of visceral states such as feeling hot, hungry, sexually aroused or angry on our own future behaviour. It seems obvious that this would have an effect on decision making and yet we, as researchers, have myopically disregarded these contextual elements. In doing so, we have succeeded in muddying the truth. If we can understand contextual elements like the mood states of respondents, we take a giant leap closer to predicting purchase behaviour at that moment, in that store, standing in front of that shelf.

I propose that we campaign for a contextual paradigm shift. Let’s start looking at the importance of context and the degree to which it adds value to insights. We need to start asking the who, how, when and where questions. If behavioural economics has taught us anything it’s that context matters. The experiments have been done, the knowledge is there, now is the time to get practical.

Brandon is an R&D analyst at TNS in South Africa

3 comments

Thanks Phil and Annie for your feedback.

The key point of the article was intended to be a simple yet significant one and I don’t think you’re too far off the mark in calling it old news.

However in my mind, this is what makes it all the more astonishing. From the perspective of someone who is relatively new to this industry, I was amazed at the discrepancy between what we know from social science research and what is being practiced in business.

The relevant news I suppose is that the industry, to a large extent, continues to operate according to past practices in full knowledge of this “old news”. To me, this makes this exercise necessary or perhaps even obligatory.

Ditto Phil. This isn’t news. This is old news. Sadly, it tells me that market researchers don’t have enough background in psychological behaviour which is the essence of market research. Unless, of course, we love calling old things by new names to make them wonderful and exciting all over again.

Nicely argued Brandon. But surely your key point should not be a surprise to market researchers. Psychologists have been saying for years that behaviour is a product of ‘state’ and ‘trait’ ie context and individual.