By Carlo Stokx

Never in Dutch Parliamentary history have the General Elections in the Netherlands drawn as much international attention as the one that took place last week.

After the UK referendum on leaving the European Union and Trump winning in the United States, the eyes of the world were fixed on the Netherlands to see if populism would win the day, and the ‘Dutch Trump’ (e.g. Geert Wilders of the Freedom Party) would institutionalize Dutch uncertainty and disappointment to become prime minister of the cabinet.

In that scenario, pollsters would again have had to explain why they were not able to foresee a tremendous win for the populist party, but the outcome has been somewhat less spectacular. Dutch pollsters have been quite successful in measuring trends and were close to the election result the day before elections. Here is why you shouldn’t be surprised about that!

Before explaining why the industry was able to restore faith in the concept of political polling, it is important to be aware of a few crucial aspects.

Six pollsters published a final poll, all via online surveys, at least one day before the elections. It must be emphasized that none of these pollsters proclaimed that their poll was a prediction of the final election result, but clearly stated that it was a proper picture of the day before.

Ipsos research on election day showed that 14% of the voters had made their final decision on election day itself. It’s plausible that big events, such as the final debate the evening before election day, could stimulate people to switch preference or finally make up their mind.

This is sufficient reason to believe that final polls could easily differ by 21 of the total 150 seats, in comparison with the final election result. The most important task of the final (online) polls was to get the trends right. Large deviations per party between the poll and election result should be explainable on the basis of what voters have seen, read or heard between the final poll and the moment they cast their vote.

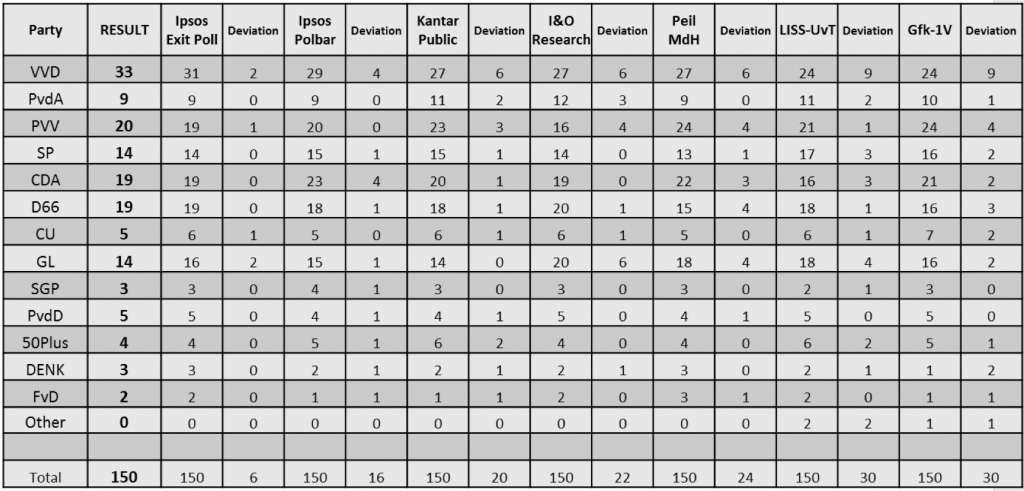

The only political research instrument that has all the right ingredients to give a reliable indication of the election result, is the exit poll. On this occasion the exit poll, conducted by Ipsos Netherlands by order of two major Dutch news agencies, was based on actual voting behavior at 43 (of 388) carefully selected polling stations on election day. As is shown over the past elections, the exit poll once again gave a razor-sharp indication of the final result. 144 of the total 150 seats were predicted correctly; thus no more than a six seat deviation overall, all within the well-known and well-explained margins of such research[1].

Learning about voter trends

One of the main reasons why the Dutch pollsters proved to perform so well is because they have learned how to measure support for Dutch popular parties over time.

Since 2002, with the rise of Pim Fortuyn, populist parties have taken a part in the Dutch political arena. From that year onward populist parties, like the LPF and currently the PVV, have played a serious part in six General Elections. For exactly 15 years Dutch pollsters thus have been able to become familiar with the reaction of the Dutch electorate to the appeal of anti-elite parties.

Efforts of pollsters to include these voting groups and know about their socio-demographic as well as their psycho-graphic variables have already been recorded over these past 15 years, resulting in an excellent sense of how they should interpret the intentions and answers given. Properly involving these groups in research is therefore less problematic for Dutch pollsters than for those in countries in which the institutionalization of populist sentiment is something new, or reactionary.

This doesn’t mean, however, that there haven’t been other voting groups that are underrepresented in almost all online panels. Turkish and Moroccan people living in the Netherlands are such examples.

From previous elections, we know that these groups have had a predictable preference for left parties (PvdA mostly) or are not motivated to vote at all. In this election, a party that has a great appeal to Turkish and Moroccan people, called DENK, has entered the political arena. For the first time in Dutch parliamentary history, a party that is eager to represent migrants in the Netherlands has managed to attain seats in Dutch parliament.

As in other countries, people with a migrant background are quite hard to reach in online polls. Different pollsters therefore deploy extra measures to explore trends in these often closed communities. For example, my colleagues at Ipsos have conducted a robust mixed mode study in cooperation with a specialized agency; using a combination of online, telephone and face-to-face research, the study included every generation of the Turkish and Moroccan communities, and explored at length their political behavior.

Other research agencies, like I&O and Kantar Public, have made similar efforts to study these groups. From such studies we learned, that DENK would have a fair chance of attaining some seats (estimated at two seats in most final polls). These additional, thorough efforts of different Dutch pollsters to reach out to these migrant groups is the reason why there were no surprises on that matter. All pollsters were right about their potential: DENK would eventually attain three seats in parliament.

Moreover, we saw a relatively ‘flat’ campaign prior to these elections. Up until the final weekend of the campaign, no major news events or political scandals could be considered a ‘game changer’ in the polls.

For some considerable time, the Liberals (VVD) have competed with the freedom party (PVV) to be the biggest in the polls. Many expected that these parties would eventually create a major distance in support from the other parties in the campaign or that other parties would benefit from an event like the previous elections in 2012.

However, this unexpectedly flat campaign led to the fact that the electorate was relatively stable until the last weekend before the elections. This absence of large electoral fluctuations caused pollsters to be quite unanimous in the trends. Moreover, Wilders’ strategy to use as much direct media (mainly Twitter) and avoid mainstream media made him less visible for the more moderate voter at the right side of the spectrum. Swing voters, who still pick up political news from mainstream media, saw too little of the Wilders’ ideas for them to get in the picture.

A last minute crisis with Turkey

As we look at the final polls, we see somewhat more divergence between pollsters than we saw earlier in the campaign. From the fluctuations recorded in most polls in the final days of the campaign we know that one particular event had an impact on the Dutch electorate.

All experts agree that this was the diplomatic crisis that emerged a few days prior to the elections[2]. Some thought that this would primarily benefit Wilders’ PVV in the polls, but a strong and impressive performance of the current prime-minister Mark Rutte (VVD) during the crisis limited the opportunities for Wilders’ philosophy to profit. The crisis with Turkey created a sense of unification among Dutch voters. Rutte managed to attract voters to rally around him and as we look at the poll results, we see the VVD, Rutte’s party, got ahead of the other parties in most final polls. One could say that as a result of this political event, the VVD “cashed-in” their so-called prime-minister’s bonus, but to be fair, almost all pollsters had foreseen this positive trend.

To conclude, what are the most important factors why Dutch pollsters managed to map out the most important electoral trends during these elections? What is to be learned from these Dutch elections for pollsters in other countries with elections coming up, like France and Germany?

From the factors mentioned above, it is clear that the circumstances were quite unique for the Netherlands. In France and Germany, populist parties have been quite new in the political arena.

There is reason to believe that Dutch pollsters have been accurate in measuring support for all types of voters because of the experience over the past 15 years. From experience, we know that the rise (and fall) of some populist parties could be closely connected with the eventual turnout.

Turnout – at 82% of the population – was the highest seen in 30 years. The PVV’s somewhat more low-key campaign, had little or no impact on turnout. In countries with less understanding of the possible impact of populist parties, turnout could be a much more dominant factor. If this experience is absent in other countries, it is essential to get to know these relatively new voters right away. Turnout modelling, different questionnaire structures and psychographic weighting factors can all help you to get better acquainted with these communities – something Dutch pollsters were forced to take into account 15 years ago.

[1] For more information on the exit poll Ipsos conducted, please contact my proud colleagues Marianne Bank or Jeroen Kester.

[2] More info on the origins and impact of the diplomatic crisis: http://edition.cnn.com/2017/03/12/europe/turkish-dutch-tensions-increase/

Carlo Stokx is Manager Ipsos NV and chair of MOA, the Dutch Research Association.