Simon Chadwick

First published in Research World June 2010

Simon Chadwick talks to Jim Collins, best-selling author of Built to Last, Good to Great and latterly How the Mighty Fall, about the role of engaging customers and research in the success of a company.

You note in How the Mighty Fall that one indicator of decline is a drop in customer engagement. Does this imply that staying close to the customer is also key for sustained performance?

It’s very hard for a company to become successful if it didn’t figure out early on how to create engagement with its customers, because that’s how you get out of the garage and begin to build your initial stores.

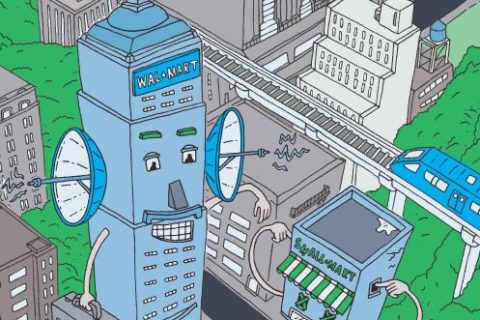

When Sam Walton started his first dime store, it took him seven years, but he had tremendous engagement with his customers. It was just a single dime store, but that’s how he then could have two dime stores, and then seven dime stores, and then ten – it was very direct and very tactile. But what he really wanted to do was to make sure not to lose that connection as the company grew, so he would listen and ask the same questions as when the company was small.

If you start overreaching and growing too fast, doing big acquisitions, you can find yourself starting to head off on adventures but lose the really simple things, like ‘How did we originally connect with our customers in the first place? Why did they love us, can we really understand that?’ And then the customers start giving you warning signs – which loyal customers will – often because they like you and don’t want you to fail.

The information may be there, but the question is will you choose to deny it or not?

What you’re saying is that listening to customers but also listening all around you is a key component of greatness.

I’m really struck by in the very best leaders that we studied is how many questions they ask; they have a very high question to statement ratio. It’s questions like, ‘Why would all those people up in Manchester all of a sudden be doing X, what’s that about?’, ‘What’s going on or why is this working, why is that not working?’ They had a genuine sort of relentless curiosity, never ever assuming that they were anything other than students.

There is a huge distinction between people having their say and people being heard. And what our Good to Great leaders did such a marvellous job of was making sure that people were heard as opposed to, ‘Well I’m going to let them have their say and then do what I want’.

When you look at the decisions in great companies that we studied – they were rarely taken at a point of consensus, they were taken at a point of disagreement followed by executive decision, and unification behind that decision. This works because in the genuine debate about what to do, the real arguments are heard. You’re really listening because you’re trying to get the right answer and because the issue is real, once the decision is taken, people will say, ‘I might have agreed or disagreed at this point but now that’s irrelevant and my job is to put my shoulder behind the flywheel and push’. Disagreement and unity is a very different question.

You just described what every researcher believes is what they’re good at, but it often seems that market research and intelligence or insight is relegated to a tactical role. Do you believe that it should be a strategic function from what you’ve seen in the companies you’ve studied?

I believe that evidence-based dialogue, debate and argument, leading to good decisions is the essence of strategy. It ultimately leads to good decisions that reflect a very deep empirical understanding of what will work and why. To me it’s impossible to imagine a strategic evolution happening without this input.

They are just so intertwined, and it’s the very definition of what effective strategy is all about; processing of good data and information, followed by discussion and argument about what it means, leading to some sensible decisions implemented brilliantly – and you can explain why they work or why they don’t. Over a long period of time, adding up enough good decisions like that, you’ll end up with a very good result.

So, to me, the question is hard to answer because it’s not so much that it is strategic, because it is, but it’s not an add-on, it’s woven into the decision-making fabric of the company.

The research industry itself has been consolidating for about the last 15 years, with a huge spate of acquisitions. In How the Mighty Fall you’re not much in favour of acquisitions. Tell us why that’s a bad thing, in your view.

Research has led us to a point where, properly used, it can be an enormously important contributor to the development of good strategies. Acquisitions are not so much something that I see as good or bad, but rather a question of why and when. Picture a ‘Good to Great’ curve which is going flat for a while and then there’s a pivot point and it rises at about 45 degrees so you get a ‘Good to Great’ transition. When you look at the companies that did that, and the companies that didn’t, but were in the same situations, what’s the role of acquisitions?

None of the ‘Good to Great’ companies did a major acquisition as a way to create that inflection; they never considered, ‘we’re only good and if we buy another company or do a big acquisition we’ll be great’. So you can’t make yourself great with an acquisition, at least not based on our evidence. Furthermore, a number of comparison companies, the ones that failed to make the leap, tried to do exactly that and didn’t make it – not surprisingly.

Now let’s look at the post-inflection point. You’re rising, being successful and on the upwards slope. We found that about half of our ‘Good to Great’ companies, and probably by now it’s much more than half of them in their best years, used one or a few key strategic acquisitions. What’s happening? They’ve got a model that works and can explain why it works; they’re in the process of replicating it and are already great. Then they see an acquisition that fits with what they already know works, and that acquisition becomes an accelerator of a model that is already working.

So it’s not ‘Acquisitions are good or bad’, it’s that doing an acquisition as a hope that it will turn you from good to great doesn’t work. Doing an acquisition can be very helpful where you’ve already made the inflection, because you’ve built the culture, the strategy and the system, and you can see how the acquisition will help you take it even further and why..

Given the increasing need for companies to receive timely, high-quality insights and evidence, particularly from consumers, what would be your key advice to the market research industry today?

Number one would be to accept the fact of being woven into the tapestry of great strategic process, as opposed to being an add-on, which means you bear a tremendous responsibility to be useful.

You need to help those around you understand that the pivot-pointed companies, on the way down or on the way up, that inflection downward in How the Mighty Fall, or the inflection upward in Good to Great, happens right at the ‘Confront the Brutal Fact’ stage or the ‘denial of risk and peril’ stage. People in this role are right on the pulse of the most important brutal fact for companies, which is ‘how are you connecting to the market, to what’s really happening and, how are conditions changing?’

Peter Drucker had a wonderful perspective, which was that the most important thing isn’t to try to predict the future, it’s to go and look out the window and see the future that has already happened. As you look, you can see that the changes are underway and that is exactly why market researchers have a great contribution. In a sense, it’s like looking out the window but with tools which are very powerful telescopes and binoculars.

I feel that your readers are a great group to reach. I’m not doing that many interviews these days but there are categories of professionals that you don’t always see, but who are in really influential roles, and that’s the way I see this group.

Listen to the full audiocast here.

Jim Collins is a teacher and author of Built to Last, Good to Great : Why Some Companies Make the Leap… And Others Don’t, and How the Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In.