The great and lamented U.S. Democratic politician, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, once famously said, “everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts.” Would that the current generation of politicians around the world would pay heed!

But in the world of commerce, research and analytics, it’s not always so simple. What might look like a fact from one set of data can easily be contradicted by another. Finding the true story to tell can often be difficult and frustrating.

In trying to solve this conundrum, the analyst needs to understand that we have to move from a world of “analysis” to one of “synthesis”. The two are not the same. In analysis, we deconstruct a singular data set to find the story. In synthesis, we construct the story out of multiple data sets, searching for patterns, congruencies or even contradictions.

This movement from one type of data treatment to the other is not easy for the died-in-the-wool researcher or analyst. Very often in the past, analysis would be undertaken by one person sitting in their office or cube, torturing the data until a story emerged. In synthesis, we have to emerge into the open and share the task. This is not just a process shift, it is a cultural one. We have to move from the culture of one to that of many.

One to many

What do we mean by this? Consider: we are moving from one data set (that of the project or the study) to many (surveys, CRM, sales, financial, social media, web analytics – you name it); we need to move from one person to many; and we move very often from one point of view to many.

Most of us intuitively understand that we are now dealing with multiple data sets. Many corporations are drowning in data and many are trying hard to make use of those data beforethey ever consider the need for primary research. But why many people? Firstly, because of the sheer volume of data and the number of data sets involved. It’s just not efficient or, in some cases, feasible for one person alone to manage all of this. But, secondly and more importantly, synthesis requires different sets of eyes and different types of brains to spot different patterns and hypotheses.

According to Root (2000)[1], there are no fewer than 13 approaches to thinking. In synthesis, we need to deploy as many of these to the task as possible if we are to spot the various patterns and hypotheses that the data may contain. This is why the key to successful synthesis is collaboration. Rather than poring over data on our own, we need to bring in as many disparate people as possible to cast their eyes and brains over the assembled data. Some of these people need not even be relevant to the assignment itself – for example, bring in people from Finance or Human Resources. You’ll be surprised at what they see that you don’t.

Connects or disconnects?

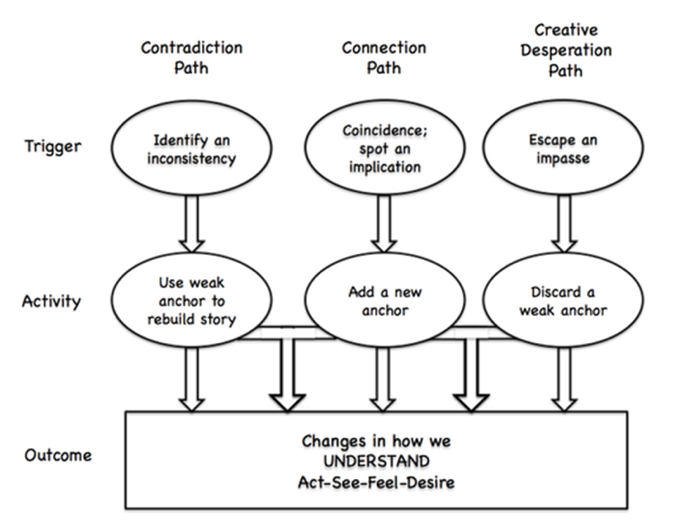

Another aspect of synthesis that sometimes seems counter-intuitive to the analyst is that we are not always looking for readily understandable patterns. As analysts, we are always on the lookout for ways to “connect the dots” (as if we were kids doing a picture puzzle). But sometimes, it’s not the connections that we should be looking for but the disconnects. Gary Klein[2]summarised this a few years ago when he published his Triple Path to Insights.

In this, he talks about the Contradiction Path where the trigger is a piece of data that just does not seem right. Assuming all methodological reasons are accounted for, this piece of trigger data can then become an anchor for further investigation.

An example of this was when a client of mine, analysing usage and attitudes towards a food category in which his client came dead last in every measure, came across one measure where it wasn’t last. In fact, it was first. That attribute was “liking”. How could that be? Further investigation found that the one group who really, really liked the product was Millenials. This set the team off on a journey for what other things Millennials liked, their values and what was important to them. Using this combined set of data, the agency was able to craft a strategy whereby the brand was cast as Millennial and absorbed their values. It was Number One in its category a year later. All because of one errant, discordant piece of data.

[Klein’s third path, by the way – Desperation – is the method used most by Sherlock Holmes in solving his mysteries].

Finally in our journey from one to many, we need to realize that there is no longer just one type of data (if there ever was). Data refers not just to numbers but also to imagery, video, text, observation. It is not just knowledge that is explicit but implicit or tacit – stuff that, in our experience, we know deep down inside us and that we can bring to bear. It can also be intuition – that feeling in your gut that tells you to follow a contradictory, outlying piece of data.

For all these reasons, synthesis is not something instantaneous or necessarily rapid. It is sometime a longer journey than analysis, requiring not only human eyes and brains but also intuition and gut feel. In a world of shortening deadlines and the need for instantaneous “insight”, it sometimes can feel out of kilter. Truth be told, we need to make the time for synthesis – and to do that, we need to automate and speed up the routine and standard processes that lead to the production of data. If automation can do that, it will be our friend in an era of much richer insight.

[1]M. Root. Spark of Genius: The Thirteen Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People

[2]G. Klein. Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights

1 comment

Simon

Excellent observation and perspective for today’s world of information.

Integration and synthesis is not new but increasingly important.