Sara Sheridan

A transitional point of media consumption – from ‘we’ to ‘me’ media: The need for research to understand change

The challenge in media research

As an industry, we face a challenge to meaningfully ‘measure’ audiences in the content they consume as they continue to move further from traditional linear TV into a world of digital content which can be consumed across a range of platforms, places and times.

As brands continue to scramble to ‘own’ this relationship across platforms, qualitative research is looked to, to offer direction as part of the race to understand how brands should innovate in a way that delivers to audiences’ current and future needs .

Recent history illustrates that much innovation intended to improve the way TV content is consumed has not yet succeeded. In 2010 examples of failed uptake were seen in Apple TV (second generation) and Boxee and, most notably in 2011 Google TV, Blackberry Playbook and Google Books failed to successfully engage audiences (though the launch of the new Google Play platform may yet succeed). As well as issues surrounding usability and cost, it seems likely to base at least some of this failure on the reality that new ideas were based on what people said they wanted. In my experience of media research, it seems that basing innovation only on what audience’s say they want is, at times, like buying a puppy for a child who has promised to love it forever and always look after it. The intention may be there, but the decision to buy a puppy based on intention ignores the reality of the child’s actual behaviour. If the parent had taken into account the child’s blatant hatred for simple necessaries such as waking up in the morning, walking and the rain, they probably could have saved themselves a dog’s lifetime of responsibility, as the reality for the child of waking up at 6am on a dark, wet Monday morning before school with a badly behaved slobbery (and now fully grown) golden retriever overshadows their initial promise. This is because it lacked depth and perspective, pointing to a foolish presumption that what we say we want is what we want, irrelevant to our current behaviour.

Individuals tend to wilfully overestimate the nature of their own media consumption – seeking to sound more tech-savvy and ahead of the adoption curve than they actually are, just like children overestimate their promise to take sole responsibility for a new puppy.

When it comes to media research, it seems there is a cocktail of reasons why traditional approaches are not perfect:

- Memory is flawed– we need to understand what people do, what they think they do, and what they think of what they do – audience diaries or recalled memory are not able to achieve this. We need to observe audiences’ lives in their own environment; from the TV they watch, to the content they stream, to the websites they browse across platforms, times and locations.

- Media ethnography is imperfect – an ethnographic approach does not facilitate real media behaviour observation. Firstly because observing media habits requires both a ‘close up’ and ‘wide’ lens which can capture media lives both in and out of the home. Secondly, because of the commercial restraint which struggles to support ‘true’ ethnography it requires sufficient time for an observer to embed in an individuals’ life. Linked to this comes the third challenge, which relates to the amount of judgement specifically tied into media choices, the ‘guilty pleasures’ which many might wish to hide in an attempt to protect their ‘identity’.

- BARB is no longer the solus answer to measurement in the UK – BARB is no longer fit to measure the way audiences consume content, as time shifting and non-broadcast platforms proliferate.

The need for research now

When it comes to the subject of behaviour change within media consumption, there seems to be no single accepted ‘truth’, but a constant conversation, with authors sitting on both sides of the fence as to whether change is occurring.

My confidence in the truth that our behaviour is changing is through my experience as a researcher, as well as (inescapably) an audience member. Proliferation of technology designed to offer greater access to content means that audiences are ever more in control. Where once personal activity may have been scheduled around particular TV moments, TV can now be scheduled around the individual – accessibility via mobile devices and time shifting, and now with technology such as Sky Remote Record this control is not beholden to personal location.

With this increase in control comes a significantly raised expectation – an attitudinal change, where once elements of media engagement were wants, they’ve now become needs. For example, factors such as the ability for all content to be available On Demand, are no longer ‘swing factors’ but hygiene factors for consumers at point of media package purchase.

The reason why it seems research must be applied now is that it seems we are at a transitional phase from ‘we’ to ‘me’ media. If we look at major developments (see Model 1) which have shaped media consumption over the past 20 years, it’s possible to broadly decipher 5 media ‘generations’:

From this we can see that generations four and five have experienced massive change in a relatively short space of time. This is driven by the growth in mobile ‘me’ screens, where traditional TV content can increasingly be consumed solo rather than with others, increasingly on a handheld non-TV screen.

This generation holds a fascinating relationship to TV, as they are in a potentially contradictory state. On the one hand, due to innovation, they have access to total control of content as a super-mobile solo experience. However, at the same time, it is possible to argue that the inherent driver to traditional TV may still hold, as a social experience. Innovation is therefore challenging what TV is at its essence; a social medium which offers individuals stimulus to come together and experience as a community, and social currency to take out into further social situations.

It seems therefore that the most valuable question to ask is not what is occurring broadly, but what is happening to generations four and five. They are at the tipping point with greatest potential for ‘me’ over ‘we’ consumption. This is not to say that generations one to three are irrelevant, but if media companies want to understand, and indeed potentially predict the change in media consumption, they must look to the people who have experienced the most impactful media innovation.

How can we use research to meaningfully understand change?

To return to the puppy metaphor, it seems that the key to understanding media change lies in not just the questions we ask but the ways in which we ask them. In order to explore the potential here, in April last year, I began attempting to innovate a new methodology to overcome the challenges of traditional media research.

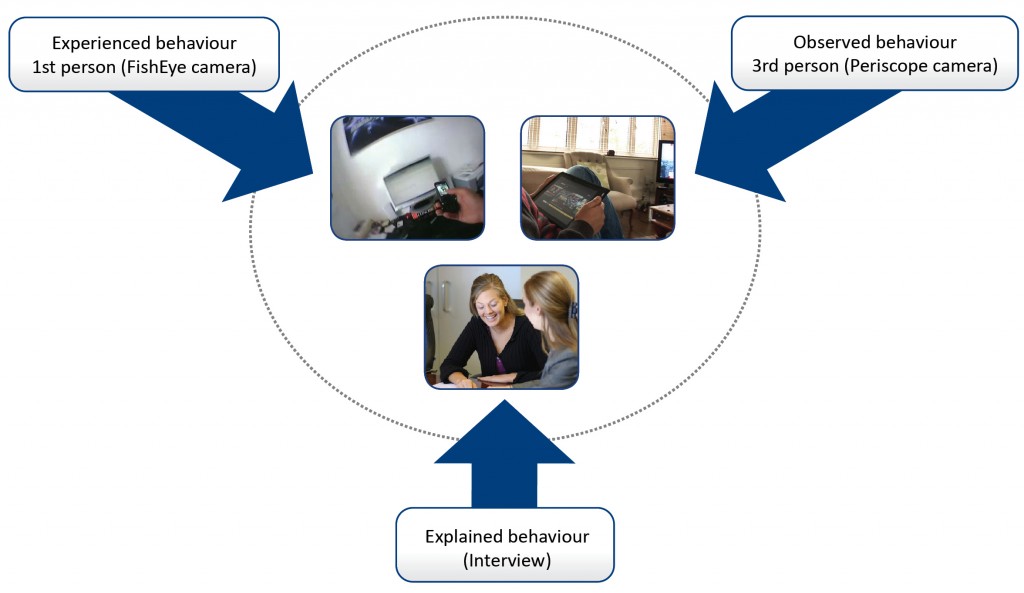

The result of this work was ‘Switched On’, offering a 360˚ model for media consumption research (see Model 2).

In undertaking this process, it is possible to gather a dynamic version of the ‘truth’ (see model 4) which can be leveraged by media companies and broadcasters in different ways.

Model 3

This internally funded project demonstrated, even with a minimal sample, that qualitative research could be used to meaningfully explore audience’s media consumption. In using Switched On we would identify insights which traditional methods (paper diaries, group discussions, BARB) could not, as illustrated below.

Case study: a Londoner’s Sunday using Switched On

Observational truth

Through observing footage from a Fisheye and Periscope camera, I saw Respondent K spend the majority of Sunday with her boyfriend, moving between the TV, PC, magazines, iPhone and iPad. There were only two brief points in the day where the couple watched TV together without multitasking. Between these, the iPad was used as a ‘floating screen’ so that whilst the TV was on, both could browse the internet. It was striking to see how much time was spent with both people in the same room, engaged in separate content.

Post rationalised, recalled truth

In a depth discussion, before showing any footage or sharing hypotheses with Respondent K, I asked her what she had done on the Sunday in question. In terms of behaviour, she recalled watching a lot of TV and ‘hanging out’ on the sofa, with difficulty recalling exactly what she watched, how she watched it or why she decided to do so. Emotionally she felt she’d spent the day with her boyfriend, a shared experience through watching the same things together in the same room.

A 360˚ understanding

In using this approach, we could isolate the disconnect between what people do, what they think they do and what they think of what they do. As an observer, we would see that Respondent K had spent barely any time engaged in the same activity as her boyfriend, yet as a moderator, we could understand that she felt she had. If we had posed the same question (what media do you use on a Sunday?) using traditional approaches, what would we have gained based on this case study? BARB would have told us that TV had been watched for 8 hours (even though it was actually engaged with once, as other platforms took priority). In group discussions, we would have gathered the flawed post-recall response as above. In a paper diary, I doubt we would have captured the times at which 3 screens were being used as well as traditional print, or the number of times the tablet was picked up for under a few minutes, and discarded once again. The act of self recording activity would have certainly inhibited the data captured.

Switched On showed us the changing role of the tablet, in this case used as a means to retain the emotional benefit of ‘sharing’ content, whilst also achieving an individual’s desire to consume the content they want to watch. An example of the new way generations four and five are using ‘me’ screens within a ‘we’ screen context. This insight, along with the case study more broadly could provide invaluable to for Schedulers in understanding how to optimise and deliver the right content accessible on the right platforms according to the type of social/solo experience audience’s want to have on the weekend. It could help to inform technology brands how to innovate against how tablets are being used in the domestic sphere.

This glimpse of insight only helps to highlight the flaws of traditional media research and the reasons as to why a new approach must be invested in now, due to the transitional phase in which it seems we’re in. As a research industry there is clearly an ever-proliferating number of questions to explore and answer, which I hope we can do so meaningfully via embracing innovation in order to become a greater part of a dynamic media world. If we continue to base innovation solely on what people say they want, we will continue to be metaphorically left having to look after our child’s now fully grown, slobbering golden retriever. N.B No golden retrievers have been harmed in the writing of this article. In fact, getting a puppy is still no. 1 on my Birthday/Easter/Christmas wish list.

Sara Sheridan is Associate Director at Firefish

3 comments

engagement and interactions are the important things to consider here and what brands and marketers will be interested in rather than just exposure.

Measuring this is firmly in the hands on, labour intensive qualitative sphere at the moment, but this will change as image recognition algorithms allow process to be meaningfully mechanised. tThis shift is atrting to happen already and will ultimately be what the media industries will see value in, buy and use in a post BARB world

As an industry, I don’t think we’ve yet developed the answer. Robust numbers are of course necessary to challenge the flawed systems such as BARB in the UK, and technology we’re currently exploring includes software which can detect what devices are on and for how long. We need to continue exploring technology options which can helps us gather more data on all devices within and outside of the home. Switched On is also part of finding this answer from a qualitative perspective. It’s necessary to understand the nature of engagement with content and devices – without this, we may just be replacing one set of numbers with another, ignoring the need for us to research the changing way in which individuals engage.

To your question: But what should we count? What is “watching”? How should we be measuring?

1. We should be ‘counting’ what devices are being used, where and for how long.

2. ‘Watching’ is a poor term to measure against, we should be exploring the nature of engagement which is not on/off but on a spectrum depending on environment.

3. We should be measuring both quantitatively and qualitatively to answer point one and two respectively.

The article currently highlights the challenges of contemporary media research. The opportunities to consume media on multiple platforms has made measurement very difficult. Unfortunately, the author does not offer insight as to how to improve measurement. She correctly explains that traditional measurement efforts are flawed. Recording additional footage of her respondents demonstrated that very well. But what should we count? What is “watching”? How should we be measuring?

In this vein, the PPM approach may offer some advice. The PPM picks up exposure to encoded channels, which would not solve the iPad challenge, but by setting the edit rules to capture exposure the PPM does not say that one was “watching.” The PPM just records that the participant was exposed to the content.