Nigel Hollis

First published in Research World July/August 2009

Culture is all-encompassing – global brands need to understand its impact if they want to succeed.

For people living in North America or Europe, the word ‘culture’ may summon up pictures of exotic places, festivals, and outdoor markets. But those of us in the West have our own cultures. Sahar S. Gabriel, a Christian Iraqi translator for The New York Times who recently moved to the US from Iraq, offers her perceptions of Western culture on the blog Baghdad Bureau: Iraq From The Inside. For Westerners shocked by the chaotic traffic in Delhi, Sao Paulo or Jakarta, she offers this counterpoint based on her experience of living in Detroit.

“They call it a traffic jam if there’s like 15 vehicles in the street. Huh? They obviously could use a trip to the entrance of Sadr City, where cars and vehicles stretch as far as the eye can see at all hours of the day. Weirder is that people wait for the light to go green even if there’s no one else in the street and no police officer in sight.”

Running a red light is not unheard of in the US, but it is not common. Adherence to traffic laws is the norm that shapes our habits. In the same way, the culture in which we live shapes our tastes, perceptions of humour, and aesthetic preferences.

The influence of culture has massive ramifications for brands. For example, in some parts of the US, people think nothing of chugging down a Coke or Pepsi to give them their first caffeine hit of the day. Where people do that, colas are in direct competition with coffee, while in other regions, the competition might be tea or some other caffeinated beverage.

In Brazil, for instance, Coca-Cola’s main competition comes from a local beverage, made from the caffeine-rich guaraná fruit, which was originally used by indigenous cultures to make a form of tea. Today, soft drinks are made from the fruit, and the total sales of these drinks in Brazil exceed those of colas.

The Guaraná Antarctica brand dominates the guaraná segment of the soft drinks market. Produced by the Companhia Antarctica Paulista, the brand exploits two aspects of Brazilian national culture (guaraná and soccer) to great effect. An official sponsor of the Brazilian National Soccer Team, Guaraná Antarctica has also devoted resources to other sponsorships within the sport.

Likewise, Guaraná Antarctica has exploited the combination of soccer, guaraná, and national pride effectively in advertising. A 2006 spot featured the Argentinean football star Maradona, suited up for Brazil and singing Brazil’s national anthem. The implied message is that guaraná captures the Brazilian spirit so well it can even infect a foreign rival.

The fact that Coca-Cola successfully competes head-to-head with Guaraná Antarctica is no mean feat. A 2008 Millward Brown survey conducted as part of research for my book The Global Brand explored the role of culture in driving brand success. This research confirmed that, all other things being equal, brands that are identified with local culture will perform better than others. But Coca-Cola’s reputation as a global brand may actually strengthen its position in Brazil.

Different degrees of globalisation

According to the Pew Global Attitudes Project, Brazilians hold their own culture in high esteem, but also have a positive view of global trade and foreign businesses. Therefore, they tend to hold positive attitudes toward foreign brands, provided they contribute to the local economy. In The Global Brand survey, we found that BRIC consumers were less likely than their peers in the US, UK or Germany to care whether brands were owned by foreign companies. Foreign brands are still regarded by many in developing economies as better quality than their local counterparts and are used as signals of personal status. For instance, in Malawi, where doing the laundry is a communal activity, those who can afford to wash their clothes with Surf instead of a bar of laundry soap are considered to be well-off.

A couple of other factors also contribute to Coca-Cola’s strong position in Brazil. The first is the care Coke has taken in adapting both its product and its communication. As a standard practice, Coca-Cola modifies its product to meet local tastes and invests heavily in locally inspired communication to complement its global positioning. Looking across countries, we also observed a strong correlation between the number of years in market and the proportion of people perceiving Coca-Cola to be part of local culture. The longer a brand has been in market, the more likely people are to have grown up with it and accept it as part of the local scene.

Food, food retail, beverages, household cleaning and personal care products are highly subject to the influence of culture because they are rooted in local taste, traditions, and needs. While it is very difficult for marketers to overcome these differences, there is no real imperative to do so. It doesn’t matter if a food brand has different incarnations in different countries; the vast majority of consumers will be completely oblivious.

High-tech consumer goods are less susceptible to the impact of culture. There are at least two reasons for this. One is that such cutting-edge products are new to everyone. Another is that these items often serve as tools, not ends in themselves (eg, the mobile phone for talking to friends and family). Items designed with ease of use in mind will readily travel across countries. The biggest barrier to brands in categories like these is often the presence of a local incumbent brand, particularly in a developed economy.

Riding the wave

Nokia is one of the most valuable brands in the world, ranking number 13 in Millward Brown’s 2009 Most Valuable Global Brand Ranking. To achieve this success, Nokia steers a fine line between the two worlds of technology-led innovation and consumer-led innovation. The company has produced a string of technology firsts: the first mobile phone to feature text messaging, the first to access internet-based information services, and the first to include an integrated camera. Nokia has also evolved its offer to meet changing consumer desires. In order to anticipate the next big thing, the company focused on leading-edge consumers in cultural ‘hotspots’. Naqi Jaffery, a wireless industry analyst for Dataquest, said: “Nokia’s advantage is that it has been involved with all of these technologies from the beginning. It is all over the world; it learns what’s good in every culture it works in, and combines it all.”

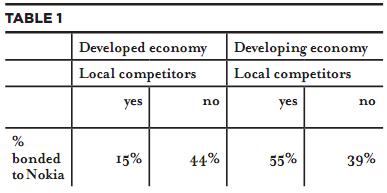

But Nokia is not preeminent everywhere. Analysis of Millward Brown’s BrandZ database finds that Nokia creates a far stronger emotional connection with consumers in developing economies than developed ones. The average Bonding score in developing economies is 55%, compared to 27% in developed ones. That difference is in part driven by the strength of local competition. In countries that have well-established local manufacturers of mobile phones (including the US, Japan, and South Korea), Nokia’s average Bonding score is only 15% (see Table 1). In developed economies where no local rivals exist, Nokia competes on a level playing field. The result is an average Bonding score in these countries of 44%, comparable to that achieved in developing economies.

Nokia benefited from riding the wave of technological innovation at a time when globalisation was riding high but it cannot afford to rest on its laurels. The Canadian brand BlackBerry has rocketed up to the 16th position in the BrandZ ranking. Apple, propelled by the success of the iPhone, ranks number six. And in China and India, brands like Lenovo, Bird, and Spice are beginning to challenge the technical superiority of global brands like Nokia, Samsung, and Sony Ericsson.

The rapidity with which brands can now establish a global footprint, leveraging the global economy to ensure cheap production and find a ready market, can distract marketers from the vast differences that still exist between countries and cultures. As globalisation continues, one might expect the challenge posed by local culture to diminish. If people consume the same brands, see the same advertising and surf the same internet, isn’t it inevitable that their preferences will become more similar? But the influence of globalisation, while far-reaching, is working against a similarly powerful force: local culture. And culture may prove to be far more durable than many marketers might expect.

Local culture

If history is to be our guide, the developing BRIC economies are likely to follow the examples of Japan and Korea in retaining a strong degree of cultural identity. One only has to contrast the US, Germany, and Japan to realise that comparable levels of economic prosperity do not necessarily promote cultural homogeneity. Since its rise as a global powerhouse, Japan has shown little sign of losing its unique culture. Global marketers still face a significant challenge in developing brands and marketing communication that will succeed in that country.

There are a number of reasons why cultural values are far more resilient than we might otherwise imagine.

- Local culture is inherited as well as taught. Today’s cultural differences can be traced back to the personal traits, physical capabilities, and societal organisation that best suited people for survival in their specific environment. From the moment we are born, those inherent traits are reinforced by what we experience in the world around us.

- Rising standards of living around the world may promote cultural diversity, not homogenisation. In her ESOMAR paper “Mapping Cultural Values for Global Marketing and Advertising,” Marieke de Mooij demonstrates the ways in which the values of national culture identified by Geert Hofstede impact product purchasing and media consumption behaviour. She concludes: “Countries may be converging with respect to income levels but they are not converging with respect to values of national culture.” An examination of recent data from Global TGI finds that economic status has little impact on cultural values. Similar values exist between rich and poor within a country, but there are big differences between people with a relatively high standard of living across countries.

- In the past, if you moved to a new country, you had to learn the local language and adapt to the local cultural norms. But today, communities of Hispanics in Los Angeles, Hindus and Sheiks in England, and North Africans in Paris find it far easier to retain their cultural identities. Global commerce brings familiar food and brands from home. Technology allows newspapers, movies and music to be downloaded in their original languages. Far from creating one global village, the internet may actually be creating millions of local ones. Brands like Google, Facebook, and YouTube have enjoyed stellar growth in part because they offer local language sites. When people can view or read whatever they want, in their chosen language, they are able to maintain their own cultural habits, wherever they reside.

Therefore, global commerce and mere exposure to foreign brands in stores are unlikely to undermine the cultural norms of the local population. Rather, as economies modernise and standards of living improve, people will celebrate both similarities and differences.

Our analysis suggests that the people who are most likely to adopt global brands are those that are exposed to foreign cultures through travel. But this cosmopolitan elite is a small minority in developing economies such as the BRICs, and this group still has far more in common with their stay-at-home peers than they do their foreign friends or business colleagues.

Common ground

The key to global brand success is to win at the local level while realising the advantages offered by global scale. Speaking of the complexity of this task in an interview for The Global Brand, Peter Brabeck, chairman & CEO of Nestlé S.A. said: “The real challenge is to combine an understanding of the complexity of the situation with operational efficiency.” In other words, a global brand should aspire to be as consistent as possible within the constraints of local market conditions and culture.

Brands that have successfully extended their equity on a global basis tend to be those built on a brand idea that appeals to some universal human need or desire. Today, concerns such as domestic violence, cancer and global warming are shared by people everywhere. Other issues are prominent in developing economies: the need for clean drinking water, deforestation and sustainable development. By embracing societal issues like these, global brands can build strong connections with consumers irrespective of local culture.

But even though an idea has universal relevance, it may not be possible to express it the same way around the world. Unilever’s “Dirt Is Good” campaign originated in the UK and has been successfully transported around the world. But the executions were adapted to recognise different views relating to dirt and cleanliness. In some countries, particularly in Asia, cleanliness is akin to a moral concern, and in some developing countries, lack of cleanliness is a real threat to public health. As a result, Unilever faced a substantial challenge in making “Dirt is Good” a global campaign. Not only did consumer sensitivities have to be dealt with, but all the members of Unilever’s far-flung marketing teams had to be brought on board.

A recent examination of Millward Brown’s Link database demonstrated that few ads can transcend cultural boundaries. We looked at ads that tested exceptionally well in one country and found that just over one in ten did equally well in another country. Moreover, one in ten of those exceptional ads actually performed below average when tested in another country. So while using the same ad campaign across borders may offer cost efficiencies, the savings may not outweigh the benefit offered by local engagement.

The role of market research

In the future, we may find that cultural diversity is less confined by national borders than it is today. Market research will play a critical role as marketers seek to identify the right point of balance between local needs and global consistency. However, that research must be used appropriately. Researchers are traditionally taught to look for differences across demographic groups, across countries, and across time, and apply statistical tests to help identify these differences.

But the most valuable insights from research will lie in the observation of commonalities as well as differences. Involvement of local researchers in each market will provide insight and guidance as to which differences are important and which are simply superficial and can safely be ignored. Local knowledge is critical to ensuring a proper understanding of context and relevance.

Where differences do exist across cultures, the question should not be “are these differences statistically significant?” but rather “are these important?” To successfully answer that question, researchers will be challenged to draw on their understanding of both product categories and cultures to unravel a tangled web of social and cultural connections that defy national borders.

Nigel Hollis is chief global analyst at Millward Brown and author of The Global Brand, published by Palgrave Macmillan.