In Part 1 I asserted that the insight industry is peddling attractive yet half-baked truths that bear little resemblance to the real world. This is underpinned by:

- Our failure to apply evidence-based thinking

- Misconceptions around the contribution of ordinary people to marketing

- Excessive focus on individuals, decision-making and the brain

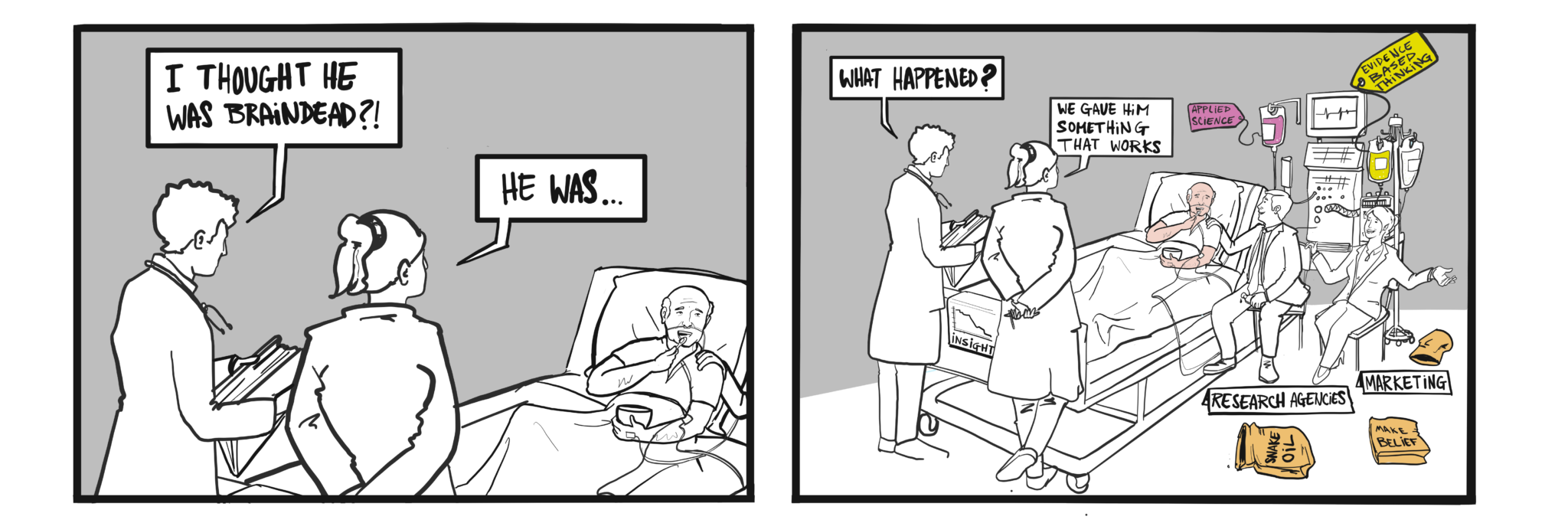

Consequently, the insights business is failing its promise of providing meaningful insight – we are only alive because we supply marketers with validation, political ammunition and outsourced responsibility.

So where to look for solutions?

- Be more scientific

Insight will probably never be a true science. Yet Lawrence Gibson asserts that it’s currently merely a pseudo-science:

“Despite its enormous growth research has made little progress as an applied science. It hasn’t eliminated the waste in marketing; it hasn’t insured success for research users; it hasn’t elevated the stature of marketing or revolutionized the practice; and it hasn’t developed a body of validated marketing theory”

Gibson goes on to argue that, unlike real science, insight’s core proposition of explaining behaviour on the basis of observed empirical data (as opposed to experimentation) is flawed because it doesn’t do justice to the complexity and fickleness of the real world, and separating cause from effect using observational data is like studying tea leaves.

Instead insight should become an applied science, applying scientific principles to marketing challenges.

These should be applied as early as the problem definition stage, which is where much of the current rot resides. This comes down to:

- Thorough problem definition before insight is called in to help

- Developing hypotheses how to fix problems before projects are initiated

- Ideally, specifying which theories will be used for analysis before data is collected

- Acknowledging the pros and cons of these theories

Currently, too often research is commissioned without clear hypotheses, let alone acknowledgment of the theories that underpin them. We’d do ourselves a favor if we’d move away from practicing a bad version of Grounded Theory – going in cold and figuring out how something works along the way − to better grounding our practices in theory. This is what real science does.

- Use people as sounding boards, not knowledge banks

Ordinary people are our lifeblood. However, we all know they have serious limitations:

- They rationalize choices

- They can’t explain their own behavior

- They don’t have stable opinions about most products and brands

- They’re influenced by fictional entities and stories (e.g. culture) without realizing it

Most of us don’t apply these well-known insights, or we don’t use them properly. As an industry that believes that ‘easy does it’, we’re simply unable to accommodate the often counter intuitive principles of behavioral economics and neuroscience. Yet given what we’ve learned about people we should stop using them as knowledge banks and minimize direct questioning[1]. We can’t just say ‘let’s go and ask customers what they think’. Instead we should use people as sounding boards for testing our hypotheses. This means focusing on people’s reactions to predeveloped ideas and concepts rather than collecting so-called opinions.

- Treat people as social beings

People are highly influenced by what others think and they’re better at predicting other people’s behaviour than their own. For example, if you want to know which political party will win an election you’re better off asking people to predict what others will vote. The wisdom of crowds beats individuals’ forecasts hands down.

Again, we know this, so let’s stop putting individuals’ views on a pedestal and incorporate the social perspective in our instruments.

- Less psychology, more culture

No matter what we are exploring, we should always ask what high-level dynamics are at play that influence behavior and include this as a standard piece of any insight puzzle. Call it cultural insight if you will.

Cultural insight is a blend of marketing intelligence and investigative journalism. For this purpose there’s no place for ordinary people. Instead we should conduct stakeholder and expert interviews, read industry and trend reports, academic journals and plain old newspapers. Whatever you do, cast your net as wide as possible and don’t be in a hurry – cultural insight demands slow, lateral thinking, coupled with a healthy dose of imagination and foresight.

- More context please

What we do, think and feel is highly context-dependent. Yet we pull people out of their natural habitats and interrogate them when they are not influenced by other people, when mindsets are cold instead of hot and when the behaviors we are studying don’t occur. Clearly there is a bewildering and continuing lack of context in our methods.

Other than acknowledging this, what could we do to make insight more context-sensitive?

- Ethnographic methods are an option; however, they are time consuming and expensive

- Fortunately context can also come from behavioral or Big Data, which is increasingly available; if analyzed properly this introduces an element of reality alongside primary research

Finally, let’s not forget that insight exists by the grace of marketing, which has its own problems around short-termism and perceived ineffectiveness. Sadly we are unable to drag marketing out of its malaise with our pseudo-scientific trickery. Yet the road out of Lalaland can only be traversed if our marketing colleagues are on board. It takes two to tango.