by Laura R. Oswald, Ph.D.

Behavioural economists agree that market value is based not only on the vicissitudes of financial markets, but is rooted in a system of symbolic exchange that trades on the meanings consumers attach to goods. If we agree that value creation is entwined with meaning production, then managing brand equity is tantamount to managing brand semiotics (Oswald 2012, 2015). In this article I discuss the advantages of semiotic research methods for decoding consumer experiences and translating them into marketing strategy.

I focus specifically on the innovative research techniques we used to decode the meaning of chronic pain for patients, one of the most elusive areas of consumer behaviour. Pain research poses unique research challenges because patients have trouble verbalizing what they actually feel. The case illustrates the advantages of semiotic ethnography and metaphor elicitation to decode the non-verbal discourses consumers use to describe their pain experiences. Findings led to a new understanding of chronic pain, based not so much on its effects on the body, as on consumers’ lifestyles and goals.

What is Semiotic Ethnography?

Semiotic ethnography accounts for tensions between the codes that structure cultural norms and the messy, unpredictable nature of human behaviour. On the one hand, semiotics brings a degree of objectivity and science to ethnographic research inasmuch as it is rooted in linguistic science and the theory of codes. It draws from Levi-Strauss’s ([1963] 1974) famous structural approach to culture, which exposes the underlying code system structuring the meaning of goods and consumer experiences in field sites. Semiotic ethnography accounts for the multiple code systems at play in the ethnographic situation, including consumer speech as well as non-verbal signs such as designs, consumer rituals, social interactions, and the disposition of goods in the lived environment. Since semiotic ethnography seizes consumer behaviour in action, and it also exposes the unique ways that consumers perform these codes in everyday practice.

Research Design

Two-hour ethnographic interviews were conducted in the homes of twenty-four men and women, ranging in age from 35 to 65 spread over three U.S. markets. All respondents had been suffering from chronic pain for one to ten years and were looking for alternatives to the pharmaceuticals and over-the counter pain medications they were currently using to manage pain.

Semiotic ethnography was used because it provides access to an array of non-verbal codes in the home environment that reflect consumers’ lifestyles, mood states, and social life. We also introduced an unorthodox methodology to the ethnographic tool kit by using projective tasks that invited consumers to associate their experiences of pain with non-verbal symbols. The two-pronged methodology exposed parallels between consumers’ psychological projections and the semiotic analysis of their domestic space.

The Semiotics of Pain

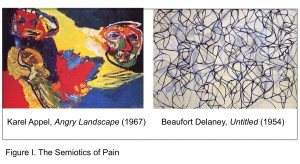

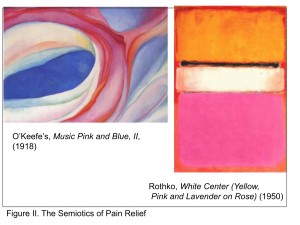

Early in the interview, respondents were exposed to projective exercises that prompted them to associate visual symbols and designs with their experiences of pain and pain relief. The visual stimuli consisted of two-dozen abstract paintings by modern artists such as Appel, O’Keefe, Picasso, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Pollack, and Delaney, where the emphasis is on form and emotion rather than the characters, stories, and landscapes of figurative painting. Respondents chose the top two images that best represented pain and pain relief in terms of visual elements, such as color or shape. Though none of the respondents met each other, and though they were chosen from the phone book rather than a database, there was a high degree of consensus in their image choices. In fact the symbolism they associated with pain developed into a kind of shared code system.

Over the course of each interview, respondents learned to associate a certain sensation of pain with specific colours and designs in the images. Over the course of twenty-four interviews, there emerged a high degree of agreement about the association of pain sensations with specific symbols and colours in the images. For example, blue stands for the self, red stands for intensity, jagged lines represent the jabbing, pulsing sensations of pain, and squiggly lines stand for chaos. Pain relief softened the red to pink, smoothed out the jagged lines, and brought order to one’s life. Respondents eventually stopped using words like “pain” or “heat” and used symbols from the pain lexicon instead. Over time a kind of “pain lexicon” emerged that enabled researchers and respondents to communicate about pain sensations by means of these non-verbal symbols.

Respondents most frequently associated two paintings with pain: Appel’s Angry Landscape (1967) and Delaney’s Untitled (1954) [Figure 1]. A semiotic analysis of the two images suggests that pain’s effects on the patient’s spirit and lifestyle outweigh its physical sensation. Respondents chose Angry Landscape (1967) because the jagged lines and haphazard movement of red, yellow, and orange against the black background resemble the chaos and disorder that that pain has introduced into their lives. The eerie figures suggest the threatening, dark mood brought about by pain; the streak of yellow moving on a diagonal from top to bottom of the frame represent pain’s heat and intensity. Respondents associated blue with the cooling, stabilizing state of the Self without pain. The patch of blue down right in the Appel painting suggests a reduced Self that is subordinated to the overall violence and chaos produced by pain. Respondents chose the Delaney picture because the irregular squiggly lines communicate the chaos and lack of control caused by pain. The blue shadow behind the lines represents the diminished self, overwhelmed by the chaos of pain.

Pain Relief

Respondents most frequently associated two paintings with pain relief: Georgia O’Keefe’s Music Pink and Blue, II, (1918) and Mark Rothko’s White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose) (1950). Respondents reported that treatments never fully eliminate pain. They associate pain relief with visuals that soften the intensity and heat of the colours, smooth out the jagged lines, and bring harmony to chaos. They also said that the colour blue, a symbol for the Self in the pain lexicon, gets bigger, suggesting that pain relief represents an enhanced sense of control and personal integrity. [Figure 2]

The Semiotics of Domestic Space

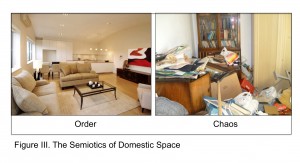

A shared consumer discourse emerged from the picture sort exercise that emphasized the effects of chronic pain on consumers’ emotions, social lives and life projects. This message was also reiterated in the semiotics of consumers’ lived environments, because life with chronic pain dramatically alters consumers’ ability to keep house, complete projects, organize their possessions, and manage their pain treatments.

A dwelling is a kind of text that is organized by cultural codes for decorating and furnishing the home. Codes articulate the domestic space into binaries such as sacred and profane and public and private domains. Social norms shame us into keeping house and organizing our possessions in tidy cabinets and closets, with adages such as “cleanliness is next to godliness.” Though each individual interprets these codes according to personal tastes and lifestyles, cultural norms account for the fairly consistent arrangement of spaces, possessions, and traffic flow within the home. For chronic pain sufferers, the home reflects the gradual decline of personal control over one’s life as the pain endures. Hoarding discarded goods is the most obvious manifestation of their inner chaos.

In the early stages of chronic pain, consumers contain the chaos by storing discarded goods in closets or extra bedrooms. In the advanced stages of pain, discarded clothing, junk, and boxes gradually extend from the private areas of the home to the public spaces. The mess fills up hallways and bedrooms and crowds the living room. Even the kitchen is piled high with dirty dishes, pans, and refuse. [Figure 3]

At one home, the respondent told researchers to enter by the back door because piles of discarded newspapers and Christmas decorations blocked the front door entrance. In these kinds of households, researchers had to remove junk from chairs and sofas in order to find space to sit down for the interview. Even respondents’ beds were piled high with clothing and papers, leaving only a small space for the individual to sleep. The goods in these homes seemed to possess the people rather than the other way around. As the chaos takes over their homes, consumers increasingly dissociate themselves from their surroundings, frozen in a state of mental denial about the dysfunctional state of their environments. In one household, a young teenager arrived home from school and dodged stacks of hoarded goods as he went upstairs as if habit had desensitized him to the environment. Patients and family members alike seemed frozen in a state of mental denial about their dysfunctional homes.

Consumers living with long-term chronic pain also collapse boundaries between sacred and profane areas of the home that traditionally define where one stores prescription drugs. Rather than storing their medications in special cupboards and cabinets in the private areas of the home, patients would leave them in public areas such as the living room and kitchen, on coffee tables, kitchen counters, and book cases. Pain treatment consumed their daily lives. Over time, patients often lost control of their medication use, leading some of them to addictive behaviours such as taking double and triple the recommended dose of over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen.

The Paradigmatic Dimensions of Pain

Projective tasks are designed to elicit information about consumers’ deep emotional and mental states, whereas ethnography traditionally focuses on the social and cultural factors associated with consumer behaviour. By embedding the picture sort exercise within the ethnographic interview and observation of patients in their homes, the study exposed the paradigmatic implication of the physical, emotional, and lifestyle effects of pain on consumers’ lives.

The two-pronged approach illustrates the reliability and objectivity of semiotics-based research. Rather than rely upon the researchers’ subjective interpretations, semiotics methods draw inferences about consumers based upon the iterability of findings on more than one level of consumer experience. From one the psychological projections to the semiotics of the lived environment, consumers reiterated – non-verbally – that the most troubling effect of pain was the chaos and lack of control it introduced into their mental states, their lifestyles, and their environment. Researchers discovered that “what chronic pain patients want” is a restored sense of order and purpose in their lives.

The multi-dimensional design of the research also bridged the gap between consumer insights, marketing strategy and advertising. Findings inspired ideas for new pain treatment products and pharmaceutical brand positioning. Furthermore, by linking the experience of pain to visual symbolism, the picture sort exercise provided insights for developing marketing communication strategies.

Laura Oswald, Ph.D. is Founding Director of Marketing Semiotics in Chicago. She can be reached at loswald@marketingsemiotics.com.

3 comments

[…] this article Laura S. Oswald discusses the advantages of semiotic research methods for decoding consumer experiences and translating them into marketing […]

Now I know what I want to be when I grow up. A semiotic ethnographer. Way cool.

I’ve been involved with semiotics since the 1980’s…and by coincidence I am reading this brilliant paper a few days before a round of x-rays and medical consults for pain.

This is my favorite piece to date from Dr, Oswald. Great work!

Steve