An occasional series by Simon Chadwick on the post-crisis future of our industry

I recently read a very thought-provoking article by Susan Fader (FaderFocus) on the need to incorporate Narrative Economics into market research. My (likely very poor) rendering of her key message is that neither traditional primary research nor behavioral sciences will necessarily work in terms of understanding motivations unless the narrative context of a person’s life is also taken into account.

But what do we mean by narrative context? Take, as an example, two families living in identical circumstances who look demographically the same: a poor white family with two kids living in rented accommodation in a town that has just lost its last factory. One might imagine that their views on things such as social security, education and drug use would be very similar. But unless we understand their narrative contexts, that is an assumption we cannot make. One family may have circles of friends who believe that greedy corporations caused their downfall, while the other may move in circles that have a narrative of distrust of government. Who to blame? Who to vote for? The outcomes may be very different.

Narrative context has become intensely relevant in today’s world. Human beings naturally need to belong (as do many other species). As such, we tend to cluster together in groups who see and talk about the world in similar terms. With social media massively emphasizing this tendency – using algorithms to ensure that we only hear from people who think like us – it becomes very easy for memes and beliefs to grow that may bear no relationship to the ‘real’ world whatsoever. Take, for example, the politicization of mask-wearing in the U.S. The scientific rationale for wearing a mask is not that difficult to understand. But if the narrative context surrounding it for some people is rooted in a belief that being made to wear a mask is an infringement of constitutional rights (and is downright emasculating, to boot), then no amount of logical reasoning is going to change people’s minds.

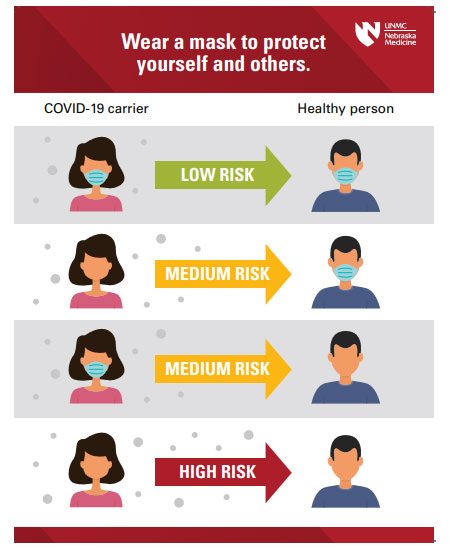

Indeed, it may actually cause people to embellish the narrative. This infographic, for example, tells the story of mask wearing pretty well. But one senior politician I am aware of didn’t like it. His base narrative was ‘infringement of rights’ but, to counter this logical message, he embellished his position by saying outright “masks don’t work for viruses”.

Now let’s take a leap forward – to the time when a vaccine against COVID-19 becomes widely available. In many parts of the world an anti-vaccine movement was already growing pre-crisis. This narrative started when a man called Andrew Wakefield fraudulently claimed in a scientific paper that vaccines were linked to colitis and autism in children. Although retracted in 2010, the narrative had already entered the mainstream and was not only embellished by conspiracy theorists but adopted by parents of autistic children and, a little later, by parents determined not to “expose” their children to the danger of autism. This led to a significant drop in vaccinations of all types and the ‘rebirth’ of diseases long thought to be conquered in the developed world.

We are told by WHO and equivalent national bodies that, in order to be effective, a COVID vaccine would need to be administered to at least 80% of a given population. If the anti-vaccine narrative prevents that level from being achieved, the consequences could be severe. So, how do we overcome these narratives in order to allow the vaccine to do its work? Behavioral economists might advocate behavior ‘nudging’ but, if the narrative context is already suspicious of such things, nudges may not succeed. Do we resort to outright mandates and make it a criminal offense not to get vaccinated? That might work in some countries but, as we have already seen on the issue of masks, some governments may shy away from such mandates for fear of alienating their bases.

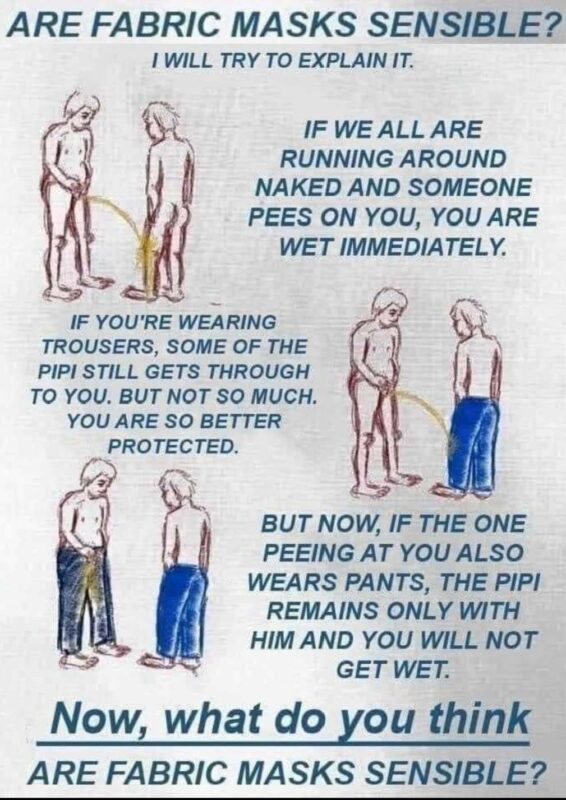

The answer seems to lie first and foremost in understanding the narrative contexts themselves and then in changing the narrative. This may involve co-opting an opposing narrative – for example, in the United States, one such ‘coopted narrative’ is that it is actually patriotic to wear a mask. Messaging could be injected into social media bubbles, although that seems more to be a tactic of Vladimir Putin and so may not be a popular approach outside Russia. Or we can create alternative narratives to put social pressure on vaccine resisters. Reverting to the mask issue, the infographic on the left is a narrative now circulating through social media to do just that – exert social pressure.

One thing is clear: if we are to change the narrative around the COVID vaccine, work to do so needs to start now. Anti-vaccine memes and conspiracy theories are already circulating around the Internet and, virus-like, will spread unless countered. But how and who?

Many people would say that this is a prime responsibility of government. But that does not work in places where trust in government is low. Where masks have been concerned, the narrative in the U.S. and elsewhere has been changed not by government alone, but by government and brands. Certain brands belong more in some narrative circles than they do in others. When those brands themselves come out on the side of something that is socially desirable (masks, a vaccine), the narrative tends to change more quickly and permanently.

But first we need to understand much more comprehensively how various narrative contexts and brands interact. And that’s where research comes in. Rather than merely study current behavior in relation to the virus and the actions needed to beat it, research needs to concentrate on decoding narratives and understanding how brands fit into their contexts. Only then will the brands be able to interject themselves for the common good into the conversation.