The answer to the layman’s question about the difference between qualitative and quantitative research will typically be something along the lines of:

- Quantitative asks “how many?”

- Qualitative asks “why?”

However, what we know about human thinking processes has led qualitative researchers to largely avoid ‘why?’ questions.

There are several reasons for why questions intrinsically (whether it is ‘why?’ or some other question) are not the best approach to gaining an understanding of how people feel, what influences their decision making, how they form opinions, and why they behave the way they do. Yet, these are the topics upon which qualitative research is often asked to shed light.

So, why not ‘why’?

The short answer is that for the most part, people don’t know why they do things or feel things. For example, a credible body of evidence shows that much of what we see and hear is processed unconsciously, so we are affected by ads that we have been in the presence of even though we don’t remember seeing them. So how can we hope to know ‘why’ we feel a particular way about a brand?

And, it is not just the intangibles like feelings that we cannot explain. We also can’t tell you why we take specific actions. Our decisions are determined by powerful mental shortcuts (also called heuristics or cognitive biases).

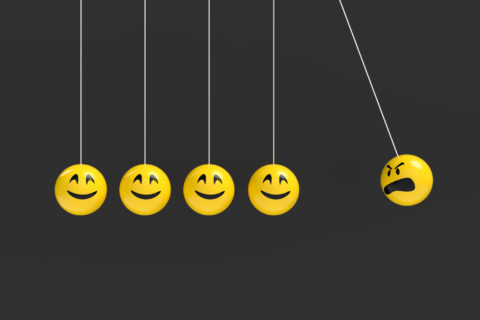

We also know the extent to which other people’s words and actions influence other people. Social desirability bias is a well-recognized heuristic, and we have all seen the effect of ‘group’ thinking, both within and outside of the research context.

So, if direct questions are fraught with danger, how can we get an accurate qualitative view?

Immersive experiences are a good tool to consider because they give the researcher the opportunity to use observation, to set and control the context, and to allow social influences to play their natural part in how people feel and form thoughts/opinions. It takes the emphasis away from direct questioning, and instead people respond in a natural and undirected way to the cues around them.

Immersive experiences … give the researcher the opportunity to use observation, to set and control the context, and to allow social influences to play their natural part in how people feel and form thoughts/opinions.

An example of using this technique is a project for an organisation that was reviewing its dress code requirements for exiting staff and new recruits. Things that were being considered included gender-neutral uniforms, personal grooming (make up, hairstyles and colour), and adornments such as jewelry or cultural symbols and tattoos.

We could have simply asked people what they felt about various options – either individually or in a group environment. We could have asked them how various options would affect their decisions or behaviour and what impression the options would leave about the brand. Instead, we set up an exhibition style immersion room with a large number of images that included staff performing various tasks, print/poster advertising, TV stills, social media posts, as well as other customer-facing print material, signs etc.

Merged in the material were examples of various dress code options – the joy of Photoshop! – with no particular attention drawn to them.

People were asked to take their time wandering round the displays – they had a few thought starters on cards: ‘I wonder if…’, ‘This makes me feel…’, ‘I think …’, ‘I noticed…’, ‘I wish…”. They were also asked to talk to the other people and given a few conversation starters: ‘What’s standing out for you?’, ‘What are your thoughts on all of this?’.

Mingling with the respondents, listening and observing gave us access to people’s natural responses to the dress code options – both in regard to their opinions, and also to how noticeable and salient they were. For example, only a very small number of people commented on the dress code variants. Whereas everyone commented on people’s facial expressions, body language and actions, noting how friendly, warm and helpful these seemed.

When we pointed out some dress code variants, we received a mixture of “I hadn’t noticed that” through to “Yes, I saw that but just thought ‘Oh that’s new’ and didn’t think much more about it”. In some instances people talked to others when they noticed dress code variants and said they had done so to see what others thought about it: “I mentioned it because I knew some people might not like it so I was keen to see what people were thinking”.

By comparison, people who hadn’t gone through the immersion process were asked for their opinion when shown the dress code variants. There was strong resistance to change and entrenched ‘positions’ on topics such as make up, jewelry and tattoos, leading people to reject these out of hand. In answer to ‘why’, people poured out socially recognised narratives about business practices. Things like ‘people should be made to follow strict dress codes’ or ‘dress codes should be very neutral so as not to offend anyone’. This was a very different response from the one we got from the immersion work.

The immersion work provided a better understanding of how the variants were likely to be received in the real world, if they were adopted. The discussions that took place among respondents during the immersion session were more like the natural, self-organized discussions that might take place in a work place or the local pub. They required very little input from the qualitative researchers and notably almost no direct questions. And, it left our client with a high degree of confidence about the likely impact of the changes.