Barriers to experimenting with innovation in CI and big data/customer analytics

Someone coming to their first insights conference or expo, or reading for the first time #mrx blogs, articles and LinkedIn posts, could be easily forgiven for thinking that market research – and the insights industry in general – was undergoing a tumultuous revolution. They would gain the impression that time-honored research techniques and methodologies were being thrown on the trash heap of time to be supplanted by new technology-driven ways of doing thing faster, better and cheaper. Go to any ESOMAR, Insights Association, MRS or IIeX conference and inevitably the focus is on the new and the future.

In many ways, this is entirely appropriate. There are indeed huge changes (some of them real advances) being made in the both our business model and the way in which we execute on our mission of understanding human beings and their decision-making, whether for social, political or marketing purposes. It is healthy to look to the future, to innovate and to search for improvement. If we did not challenge ourselves (or respond to new external challenges), we would be doing a singular disservice to ourselves, those that we work for and society as a whole. And it has been amazing to watch the venture capitalists and private equity firms come to view what previously had been a sleepy backwater of commerce with such enthusiasm and involvement – culminating in billions being invested in insights over the past decade.

Where innovation does happen

And yet there is also a counter-narrative that we hear often – that the research industry is slow to innovate and that its core is dying as a result. Indeed, I myself have been guilty in the past of wondering in print about this. Time after time in the industry studies that Cambiar put out, clients were claiming to be innovating at a faster rate than their suppliers. Time after time, the GRIT Report would notice the same phenomenon. When I talked to research company CEOs about this, they had two responses:

“Yeah, clients say that and they talk a good talk, but they don’t walk the walk”.

“If I invested in offering everything clients said they were doing, I would go bankrupt tomorrow.”

It turns out that these CEOs probably had a better finger on the market than we pundits did. A couple of years ago, when Cambiar teamed up with BCG and Yale to study the management of insights in large organizations, we decided to delve in to this seeming conundrum.

What we found was interesting, to say the least. Superficially, it was indeed true that clients were innovating, but the vast majority of that innovation was where there was low-hanging fruit in terms of cost and speed. Faster, cheaper yes – but not so much the better. And so we saw wide-spread adoption of DIY platforms (there’s a reason why Qualtrics grew as it did), the removal of tactical and rearview mirror research to automated solutions (think Medallia and Zappi) and relatively rapid adoption of digital qualitative. What we did not find was investment in more fundamental improvements in the way in which research could be used better to understand the human and consumer condition. That was left to the realm of behavioral and transaction data analytics – and even then that was driven more by the ubiquity of data, advances in analytic technology and the cost of data reducing to near zero than by any feeling that this improved real understanding.

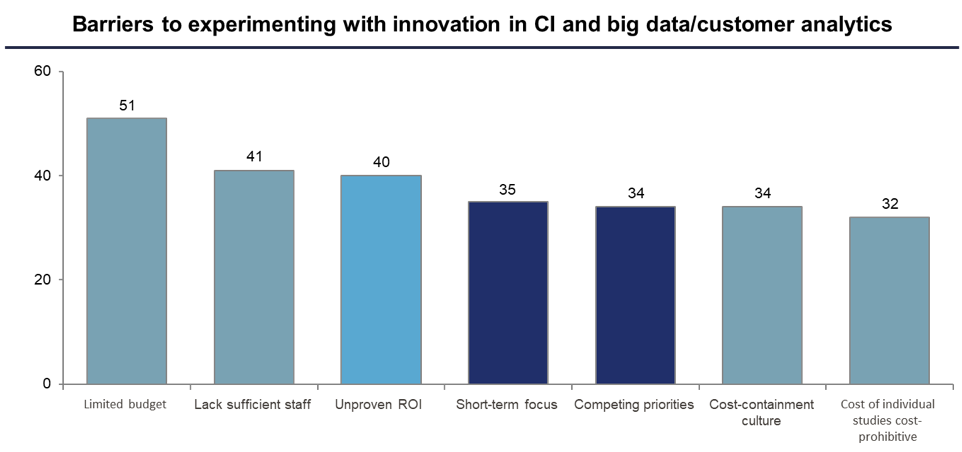

When we delved further, we found out that there were two major reasons behind this state of affairs: (i) lack of innovation or strategic budget; and (ii) inertia.

Respondents (who were senior users and practitioners of insights) reported an over-emphasis on the short-term and the tactical and a lack of prioritisation for innovation per se.

This is not to say that there is no innovation or that this situation will last forever. Indeed, we work with plenty of corporate insights functions that are doing outstanding work of an innovative nature and I suspect that these will be the ones who eventually will provide a much greater return for their enterprises.

Inertia vs progress

Just as often, however, I come across really surprising inertia in the face of incontrovertible evidence of a methodology or technology really improving what we do. Take sample quality, for example. In the face of long-standing complaints about the quality of panel sample, there are two companies that have separately introduced a new way of sampling (both offline and online) that would take us back to our probabilistic roots, significantly improving data accuracy at no extra cost. The methodology, at its base, could be called redirected inbound sampling. It has been tremendously successful among foundations, NGOs, academia and government – but has received zero interest in the commercial world. Why not? Because of inertia. When I quiz clients about this, they all agree that online sample quality is a major problem but not for them. “We’ve worked it out”, is what they say. “Yeah, sure” is what I think but am far too polite to say.

Similarly,

Behavioral Economics. This science has allowed us to make enormous strides in

understanding how human beings, ever irrational and driven by their emotional

brains, make decisions. And yet it is still an infant in the world of research

despite offering practical and pragmatic ways of improving the way in which we

interact with research participants and analysze

their responses. Again, the reason seems to be inertia – why mess with the way

in which we have always done things, especially if it will cause changes in the

data?

These two examples (and there are many others) are both poster children for how the new can indeed be integrated with, and improve, the old ways of doing things. And yet they are struggling, while the cheaper and faster technology-oriented approaches are taking off, arguably in some instances at the cost of quality. I remain confident, however, that many of these improvements will indeed seep into established methodologies, proving that there is life in the old dog yet and that all the glistens is not gold.