David Soulsby

What keeps an innovation director awake at night? A quick trawl through a selection of company reports would suggest: How to get more successful innovations to market faster

Getting ideas to market faster requires prioritisation of the ‘winners’, so identifying those ideas most likely to succeed early in the innovation process is vital.

We recently conducted an analysis of around 3,500 consumer goods launches, which shows just how few of these product innovations really add value when you look at the whole portfolio.

Our study covered all new product introductions in the UK from 2007-2011 across four categories: laundry detergent, savoury snacks, soft drinks and skin care. It found that three in five launches (60 percent) resulted in a zombie or a cannibal brand: failing to deliver long term growth, or actively eating into the market share of sister brands within the portfolio, respectively.

Market research companies claim to be able to predict innovation success, yet these figures show how often manufacturers are missing the mark. The problem is that the research industry is still using an outdated premise of innovation success, and metrics that are not fit for identifying the real stars of the future.

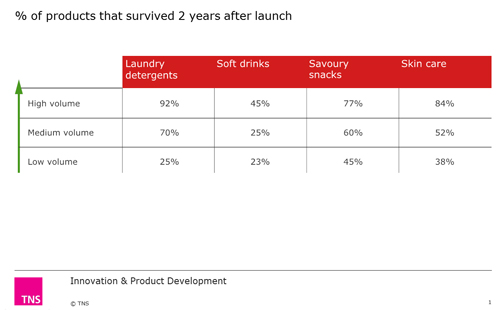

The common definition of innovation success in the research industry is survival: is the product still in distribution after two years? This definition, born over 30 years ago, is a remnant from a time of limited choice and a much simpler marketing environment.

However, our approach is based on the belief that only innovation which drives business growth (either top- or bottom-line) should be termed a true success.

Classification of ‘success’

So how did we go about determining this? To classify success we looked beyond survival to consider what impact the new product had on the business/parent brand sales relative to the average growth in the category.

Based on business impact, we subdivided the ‘survivors’ into:

- Expansion innovation: the business/parent brand grew 10% or more above what would have been expected (by natural category growth)

- Standard innovation: the business/parent brand grew in line or marginally ahead of expectation

- Cannibal: the business/parent brand contracted relative to expectation

And those that ‘died’ within 2 years of launch we classified as Zombies.

Success drivers

To explore the metrics which predict true innovation success we looked at:

- Total sales volume for the new product – classified as high, medium and low based on a percentile analysis of all launches.

- The percentage of new product sales which were incremental to the existing business.

We then analysed household panel data at an individual level to determine whether the purchases of the new product were cannibalised from the parent brand, or whether they were incremental.

Each new product was then classified as high or low incrementally on a simple percentile basis.

Results

Traditional view: Success = survival

This table clearly shows higher volume correlates with the historic measure of success, i.e. survival, but does it correlate with successful growth?

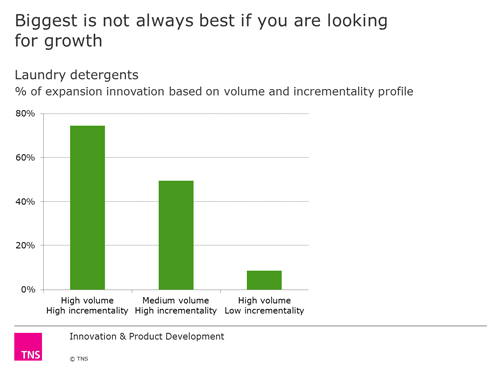

Revised view: Success = growth

When we apply a more stringent measure of success – whether the business/parent brand has grown substantially beyond what would be expected – the interpretation is very different.

Overall, only 15% of products launched provided significant growth and could be termed expansion innovation.

The chart below illustrates for the laundry market the proportion of launches classified as expansion innovation based on three specific profiles:

- High volume with high incrementality

- Medium volume but high incrementality

- High volume but low incrementality

75% of high volume high incrementality launches grew the franchise, contrasting starkly against only 9% of high volume low incrementality launches. This pattern applied across all the categories and shows true innovation success is most dependent on high incrementality, rather than high sales volume per se.

Biggest is not always best if you are looking for growth. Indeed, a new product with moderate volume potential but high incrementality is a much better bet when you are looking for growth than a high volume cannibal.

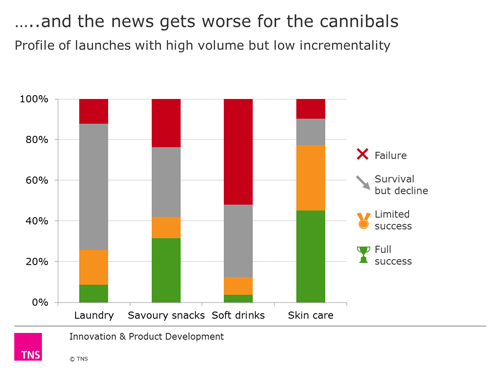

Innovation that shrinks brands

But the real worry is revealed by the profile of the launches with high volume but low incrementality. A large proportion of these types of launches actually led to shrinkage of the overall business despite the high sales volume for the new product – in 3 of the 4 categories more than 50% of the launches were either cannibals or zombies.

How could this happen? Because launch factors can impact existing brand sales:

- With non-elastic shelf space, retailers often apply a ‘one in, one out’ policy to accommodate the listing of the new product, resulting in lost sales of an existing variant.

- The marketing funds to launch the new product are often ‘stolen’ from the parent brand budget

If the new introduction is not providing significant incremental volume, the decline in existing product sales will often outweigh the new product impact.

This illustrates the danger of the focus on big ideas perpetuated by traditional thinking. Yet traditional research continues to promote the concepts with the highest purchase interest, the greatest appeal or the strongest concept potential without taking consideration of how incremental the idea is.

Why? Because predicting where the new product will source its volume from isn’t easy. Traditional aggregate models do not carry the same accuracy claims for source of volume as for total volume forecasts. In fact they often don’t make any accuracy claims around source of volume which can give permission to the innovator to ignore the cannibalisation estimate if it doesn’t ‘fit’ the business plan. And source of volume is usually considered too late in the innovation process. After millions of dollars have been spent on development and testing, making the call to discontinue the launch is extremely difficult.

To raise the accuracy and profile of source of volume analysis requires a more granular approach to forecasting. Individual modelling gives extra weight to those consumers with higher probabilities of purchase and higher frequency buyers. The result: validations show double the accuracy for source of volume generated from individual modelling versus a traditional aggregate approach.

Conclusion

In today’s fragmented marketing environment, the research industry cannot rely on metrics based on predicting survival. Survival is not good enough for businesses looking for growth from innovation.

Our results show definitively that the old ‘biggest is best’ premise is seriously flawed and outdated. It may help innovation consultants predict whether a new product will survive, but it doesn’t guarantee true success or growth.

A minimum level of volume is a pre-requisite to launch, so total sales volume is still important, but our analysis shows the key driver of successful growth is incrementality. So far we are the only company to incorporate incrementality as a key metric throughout the innovation process and to use individual modelling to increase the accuracy of this measure. However, until this is standard practice, businesses will fail to make money on more than half of the ideas they take to market.

Timing is also crucial. Currently, source of volume tends to be evaluated towards the end of the innovation process, but this is too late. At a minimum, it has to be added to the KPIs for the opportunity identification and concept screening process – because once an idea has been given the green light for development it is difficult to stop the launch.

So whilst cannibals and zombies are the stuff of nightmares for innovation directors, it is possible to keep these profit-guzzling menaces at bay. However, it requires shedding some of the most basic assumptions on which the innovation process is based, and recognising the damage that can be done by prioritising a product purely for being a ‘big idea’.

David Soulsby is Global Director, Innovation and Product Development, TNS