Author Jonah Lehrer talks to Jo Bowman about neuroscience, creative genius, and watching people mop their kitchens.

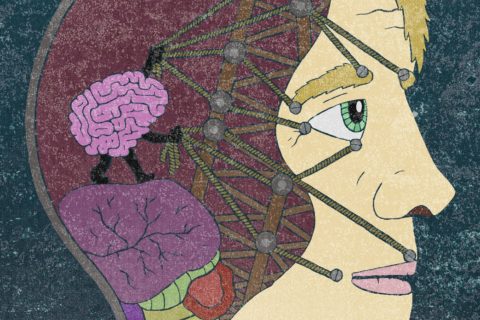

It’s not that long ago that the workings of the human brain were a near-complete mystery to the non-medics among us. But advances in ‘brain reading’ technology that allow us to see how the mind moves – from choosing a jar of jam to solving crosswords or even falling in love – have recently delivered a slew of neuro terms to the public lexicon.

Jonah Lehrer has studied the way people make up their minds; the information we use, the parts of our brain that ‘light up’ in response to different stimuli, and how the decision-making process differs depending on what we’re doing or buying.

“This is the brain – the computer we all have inside our heads,” he says. “It drives all our insights, from whether we buy Coke or Pepsi, to who we decide to marry … going forward, it has huge applicability,” he says.

The potential value of neuroscience to brand marketers is cause for considerable excitement, Lehrer says, but it’s not the Holy Grail. “In the past couple of years, there’ve been some sexy new tools like FMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), and the public really ‘gets it’ when you can see pictures of the brain at work. It’s like breaking open the black box … but the challenge is to come up with better tools to understand it. There’s a good debate to be had about what these pictures are showing.”

What brain scans are not showing, Lehrer says, is the way all market research will be done in future. Like other techniques, it’s very good at some things, and not so good at others. FMRI can clearly identify when the brain has a breakthrough moment – a sudden flash of insight that apparently comes from nowhere – but its power is more limited, Lehrer says, when it comes to monitoring complex operations in the brain that involve activity in multiple areas simultaneously.

The rapid development of neuromarketing does not, then, start the clock ticking on the future of more traditional research methodologies. “It’s absolutely not ‘either or’,” Lehrer says. “What makes human nature so interesting is that we need to look at multiple levels of what’s going on … that’s the only way to understand what’s happening inside the head of the consumer – not just put them in a brain scanner but put that information in a larger context.”

Ping-pong epiphany

Lehrer has been using neuroscience to come to a deeper understanding about creativity in the brain and the way we solve – or struggle to solve – problems. The moment that a solution suddenly dawns on a person comes down to a flurry of activity in the anterior superior temporal gyrus. This part of the brain brings together words or ideas that are remotely associated, and it works best at times of relaxation and being in a good mood.

“If you give most people a hard problem, they’ll drink another coffee, take some Ritalin and try very hard to work it out,” Lehrer says. “That’s the exact wrong thing to do. When you focus, you make it hard for your brain to make those remote associations.” It’s when you go for a walk or soak in a hot bath that you relax enough to be able to hear this part of the brain that has plucked the right answer seemingly from thin air, and voila, you have a eureka moment.

The now-famous ping-pong table at Google’s headquarters is clearly not there solely out of employer benevolence. “They know that if you give people really complex problems, it’s good to not have them stare at their computer screens all day,” Lehrer says. “Let your mind wander or play ping-pong, because chances are it’s when you’re playing ping-pong that the answer will come to you.”

However, not all problems can be solved in this way. The relax-and-let-it-come-to-you strategy only works when the answer to a problem takes an ‘aha’ moment. But some problems take doggedness rather than a flash of brilliance to solve them.

In these cases, and this applies particularly to business problems, it’s vital that those doing the solving have their mind focused on the right problem – something Lehrer says isn’t nearly as simple as it sounds. “The assumption is it’s easy to know what the problem is. In a lab, it is, but in the real world, it’s much more difficult to know we’re attacking the right mystery.”

When Procter & Gamble recruited a research company to videotape householders mopping their floors, they were hoping it would help lead them to developing a new kind of floor-cleaning product. What researchers found was that 65% of the time people spent washing their floors was actually spent cleaning the mop, and this area was where P&G could make a big difference to the consumer. Cue the Swiffer, the cloth-based floor-cleaning system that does away with the need for traditional mops.

The genius of strangers

The fact that a set of eyes from outside the client company was able to spot this is no accident, Lehrer says. Most people are better at making a breakthrough if the problem they’re working on is some distance away from them, whether that be in a slightly different discipline to the one they’re usually working in, or there’s actual, physical distance between them. Lehrer says scientists have been found to be quicker at solving a problem when they think the people they’re solving it for are in another country rather than in the lab next door. The web site innocentive.com, where businesses offer rewards for solutions to complex industrial problems, has shown that the best chance of a solution comes when a specialist from a field not directly related to the issue is involved. When a diverse group of specialists from outside are on board, the chances are even better.

“One of the reasons impossible problems seem impossible is because the people trying to solve them are locked into a particular way of thinking,” he says. Outsiders are not bound by these intellectual shackles, says Lehrer. “Sometimes all it takes is a good question to allow an insider to think about something in a new way.”

This doesn’t sound like it bodes well for research and development departments. “Make sure you’ve got a diverse team,” is Lehrer’s advice on R&D. “People are very good at slipping into the outsider’s perspective.” Researchers are also very good, Lehrer says, at finding ways to exclude data samples that simply sound wrong or buck the trend being shown by other research. These apparent anomalies should be more closely examined; they might just contain the keys to a breakthrough.

If diversity is an asset, and outsiders can often see what people close to a problem cannot, then what does this mean for the drawing of research panels? Lehrer isn’t sure, though he does believe it underlines the value of a well-run and – crucially – well-analysed focus group. He points to a group session run by MTV to illustrate where market researchers might miss the forest for the trees. Participants in the MTV study were given a dial to turn up or down while they watched a programme to indicate their level of enjoyment as the show progressed, but at the climax of the show, enjoyment appeared to fall off a cliff. The researchers found that it was not that viewers didn’t like what they were watching; in fact, they were so absorbed by it, they forgot all about turning their dials.

“In the same way as the secret of decision-making is to think about thinking, to understand a focus group and get inside their head, don’t just take the results at face value. Focus groups are an important source of information; it’s not the word of god.”

Jonah Lehrer is the author of Proust Was a Neuroscientist and the bestseller How We Decide.