How should brands adapt to consumers’ complex and contradictory sustainability behaviour?

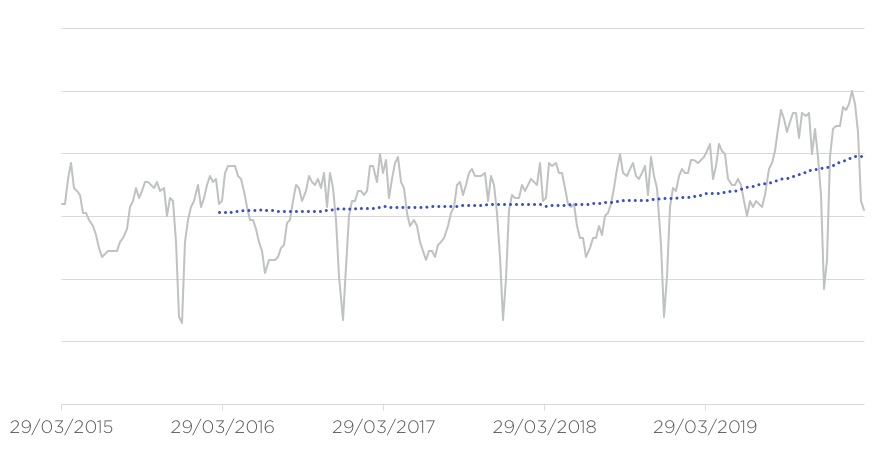

Climate and sustainability are increasingly important to a growing share of the population. We read daily about protests, activism, innovation. Greta clashes with Donald at summits. Our children strike for their futures.

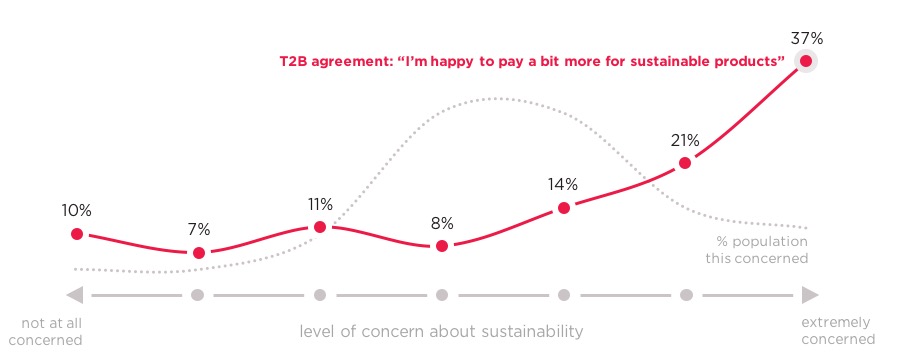

Four out of five of us are concerned about sustainability. And consumption habits are changing: the rising use of reusable cups and water bottles, the declining use of plastic straws, growing interest in meat alternatives.

But these are matched by countless counterexamples of our unsustainable ways. We still buy fast-fashion and take more flights than ever; 80%2 of passenger miles are travelled by car – while home deliveries and returns add millions of commercial miles. Willingness – or ability – to make sustainable changes is not universal.

So why are behaviours changing in some areas, but not others? In most purchase decision moments, sustainability considerations are not the foremost consideration. Purchases in the age of sustainability are driven by the same factors as always – convenience, utility, desirability, social pressure, cost. However, sustainability has changed the meanings of and dynamics between these factors.

How can brands pre-empt these shifts – and avoid missing the boat?

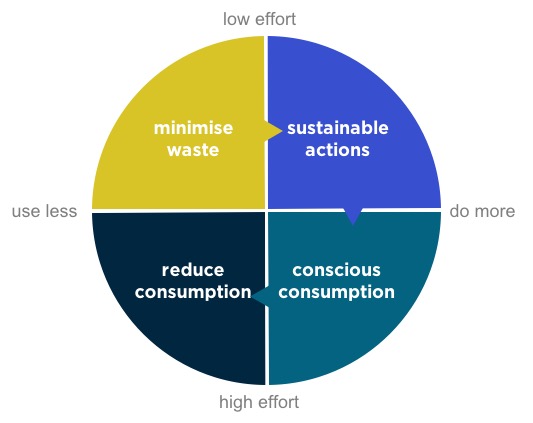

1. It’s more rewarding to do more for sustainability, than to use less

The rational, obvious solution to sustainable consumption is simply to consume less. Buy fewer clothes, packaged foods, luxuries. Use less everything. But that isn’t how consumers are responding to the sustainability challenge.

It’s easier instead to adopt sustainable behaviours that people can add to their usual habits. There’s less deprivation in taking a KeepCup than in not getting a coffee. It’s easier to switch to a green energy provider than ration the use of appliances.

However, in adopting these simple, discrete behaviours that slot neatly into their lifestyle, consumers often find that their engagement with the topic deepens. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle of cognitive consonance – a small behaviour change to align with your beliefs, which in turn validates and reinforces them. Dabbling with Meat-Free Mondays or Veganuary can be the gateway to full-blown Veganism (or at least long-term meat reduction).

So, brands looking to burnish their sustainability credentials should create sustainable brand actions that people can introduce into their life without great sacrifice and consider implications and next steps if these are to drive greater engagement.

2. Consumers adopt new behaviours when they are more sustainable and better than the alternative

When we look at what new sustainable behaviours consumers are adopting and examine why, sustainability is never the whole answer. In fact, it’s rarely even the most important reason.

Eating less meat is healthy – and it’s also more sustainable. Public transport is faster and more convenient for a planned trip. Solar panels and smart thermostats save money. Who Gives A Crap makes toilet paper ‘cool’ and delivers to my door – oh and there’s no plastic packaging.

Established sustainable behaviours all have something in common: sustainability is not their only or even their main benefit. They have clear, inherent advantages unrelated to sustainability. The sustainability angle may be the talking point, or a sweetener that seals the deal, but it’s not the whole story.

For brands looking to respond to sustainability with new propositions or offerings, the message is clear: make sustainability a secondary benefit. Focus on what makes your product better for the consumer first, and for the planet second.

3. New solutions can drive sustainability thinking into blind spot categories

Numerous areas remain where sustainable alternatives are too expensive, too complicated, or unavailable. Here even the most sustainability-conscious consumers turn a blind eye:

“Those TePe brushes must be an ecological disaster – but what am I supposed to do? Not look after my teeth?”1

Aviation, personal hygiene and pet care are prime examples where the alternatives require too much compromise, or offer too little benefit, so most consumers simply ignore them.

But while there may be a sustainability blind spot in a category today, brands can’t be complacent. These blind spots only exist due to a lack of better alternatives. Disruptive sustainability innovations can suddenly change the rules of a category. When some newspapers began using degradable bioplastic wraps for their supplements, other newspapers suddenly looked irresponsible. No one hesitated over 6-pack rings until Carlsberg introduced the Snap Pack.

Some categories will be revolutionised by environmental issues, and others will be largely unaffected. A solid understanding of how consumers behave and of how sustainability interacts with other category dynamics increases brands’ ability to predict its impact, adapt and survive the sustainability battleground: by creating sustainability actions that consumers can participate in; by designing sustainable alternatives where sustainability is secondary to some other benefit; and by being alert to blind spots and innovating sustainability into them.

1 Basis Research – The Sustainability Playbook, 2019

2 Department for transport – Transport Statistics Great Britain, 2019