A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, perky young men and women in Silicon Valley and its overseas dependencies (Shoreditch, Stockholm and Berlin etc) would proudly display their technophilia and faith in all things digital on their chests – “tech will save us” went the strikingly positivist slogan. “Tech” – technique, technology and process methodology – would always be the answer. Better tech, better answers. Better tech, better solutions, better lives, better everything. How very Dan Dare!

Still today we find ourselves as a culture looking for shiny new things: better “treatments” for medical conditions (ideally based on something atomic, genetic or smart). Rather than embrace the human side of the equation, we leap on the promise of a super smart algorithm to make decisions for us. Rather than work harder in understanding how our organisation’s communications might work, we’ve bought the whole “advertising is over” spiel and are left wondering what happened to sales growth. Rather than deal with the real deficiencies in our service to customers, let’s automate the feedback channels (and really annoy them while we’re at it!). And as researchers, rather than think just a little harder about what it is we’re trying to measure, we default to Big Data, biometrics and Machine Learning to save us.

This is a mistake. A culturally shaped mistake, for sure, (there’s a very strong mechanistic positivist strand in our culture) but a mistake nonetheless: smarter thinking can lead to better questions and thus to answers, using less data can help us find better answers and fixing the stuff we know is broken (because our customers have long told us about it) will always beat a slightly more precise measure of Brand Equity (whatever we think that is).

It’s not that technology – technique, method, process – won’t help; it’s just that its value always depends on people and how we use it. Technology is all too often a displacement activity.

Tech won’t save us from the future

Nowhere is this most prevalent than in business’ thinking about the future.

Right now, the future is hot, (who needs to think about how we got here or where we are so long as we can focus on what is yet to come). More data, more feedback loops, more oversight, more at risk and more fear of becoming one of those case studies of The Boy/Girl Who Didn’t See It Coming: all of these makes it feel harder than ever before.

It’s always been hard. The English playwright, Tom Stoppard puts it very well in ‘Arcadia’: “it’s all very noisy out there. Very hard to spot the tune. Like a piano in the next room, it’s playing your song but unfortunately it’s out of whack, some of the strings are missing, and the pianist is tone deaf and drunk – I mean the noise! Impossible”.

Which is why every human culture prizes those who can see through the fog of the present into the light – those who read the meaning in the flight of birds, in the entrails of animal sacrifice or the pattern in the tealeaves; those who hang about outside nightclubs or Fashion College Degree Shows to hunt cool kids and cool looks; those who wade their way through unsigned bands and artists to pick out Coldplay or Stormzy from the hopefuls.

[As it happens, it seems you just have to be right once to attain Madam Arcati status as all-seeing crystal ball cuddler. Just as most of the fashion journalist’s “10 pieces that are essential for your Spring/Summer wardrobe” will be on the remainder rail by the end of May, so most gurus’ predictions about consumers are as painfully misguided as they are pleasantly plausible (we all want the Faith Popcorns of Marketing to be right – after all we pay them for their visions more than handsomely and they are so convincing).]

For many in our world of market research, The Future is now the killer app – our clients no longer hang on our every word in other subjects but the Future…boy! And if you’re struggling to justify the investment in all that AI analytics power, what better subject to throw it at than the Future?

Rethinking the future 1-2-3

Let’s be straight: the future is generally hard to predict with any confidence, primarily because of the way we think about it, not because of the tools we use (although they can help when you sort your thinking out).

I’ve identified three related kinds of problem that really hold back thinking about what lies beyond the mist.

Each of these presents a significant and real hindrance but together they distort our best efforts at embracing the future.

First, it’s not just good enough to predict the future as precisely as we can and all will be well: all organisations and all individuals are prone to cognitive biases which shapes what they hear and the decisions they make. The excellent 2017 report by HMG’s Behavioural Insights Team demonstrated that the same kinds of biases observed in individual consumers are just as prevalent among those at the top of (policy) organisations – if not more so. Optimism bias (we are unrealistically positive about our own and our organisation’s abilities); Confirmation bias (seeing and hearing only what you want to); Loss Aversion and so on. When thinking about the future, all organisations are going to ignore what they don’t want to hear, they will be gung-ho when caution is required and cautious when change is needed. Whatever the technology you might use to deliver your prediction.

Second, we have to go beyond describing the future with ever more precision and instead – following Marx’s comment on philosophers – to start change it. Too much thinking about the future is action-lite: it describes the world as we think it might be (“in the future, we’ll all be eating insects/driving jetcars etc”) but not what the organisation needs to do about it.

Organisations are often described as Supertankers and with good reason: they are big, heavy and slow to turn around. The more successful they are, the harder it is to re-direct them. They are easily outmanoeuvred by smaller more agile competitors. If we Futurists want our work to impact on these organisations we have to get them to think through action, not by providing information.

And finally, straight line thinking makes The Future a singular thing: a yes, no, right, wrong thing. When we think about the future (or the past) we tend to describe it in terms of a single causal line projected from now into the future (or a single causal line which leads from the past inevitably into the present).

This is another cognitive limitation to the way we think about the future – a limitation that is probably part-psychological (the product of our inherited physical mental abilities) and part-cultural (many other cultures are happy embracing alternative stories about the past and the future; indeed, many have a much less rigidly linear view of Past-Present-Future than we do. Hindu beliefs in reincarnation are one example of this; Australian First People’s continuous time is another). Useful future thinking needs to find a way to embrace multiples, probabilities and change over time.

Do or not do?

How might an approach that embraces these three problems work?

First, we don’t tell people what the future will be like: we create games that

i. help organisations explore multiple new scenarios based on our work and theirs,

ii. to assess the challenge to existing practices, ecosystems and business models and

iii. to identify the key actions the organisation needs to take to start to respond.

Like De Geus and his Scenario Planning but on steroids: we do this fast and at scale: in half a day a team of 20 executives can create 20-30 scenarios from a judiciously selected and curated set of prompts (yes, a card-deck) and provide the initial response and evaluation for all of them.

By exploring and mapping such a large number of scenarios, our participants are able to see commonalities – those critical issues that cross scenarios that the organisation needs to act on immediately (but might otherwise be able to ignore, discounting and deprioritizing what it doesn’t want to hear).

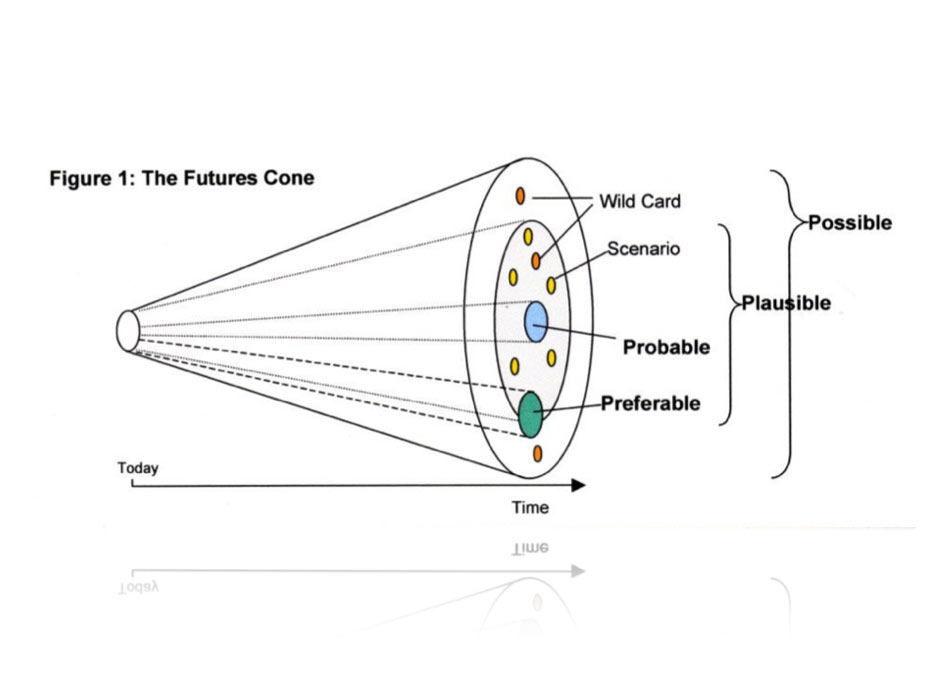

After this session we/they can check the estimated probabilities of each scenario and the precise risk it represents. Indeed, we encourage clients to use the classic probability cone (Fig 1) to monitor over time how the identified scenarios come closer and drift further out in probability. This is the place for those fancy AI tools to help and not before.

However, it is the work by the team together on multiple scenarios and the actions the organisation needs to take which makes the real difference. As the 20th Century British painter, Paul Nash put it, “if you want to understand a landscape, you need to put something in it”. We help teams understand many different landscapes by putting things in them.

In effect, the Future comes closer to the organisation and its executives; it becomes more real and more than a single place; it’s not some hit or miss theoretical thing; it’s not accessed by magic or intuition or Machine Learning. It’s something all of us can think about and act on. The Future is ours – yours and mine.

1 comment

Nice article mr e