COVID-19 has hit the world like a baseball bat to the face. Yet some countries are faring far better than others. Why?

On February 12, 2020, Professor Geert Hofstede drew his last breath and shuffled off this mortal coil.

A Social Psychologist and Professor Emeritus of Organizational Anthropology and International Management at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, Hofstede was best known for his pioneering research on cross-cultural groups and organizations.

A generation of researchers in fields ranging from marketing and cultural anthropology, to social psychology and political science, owe an extraordinary debt of gratitude to the insights Hofstede imparted through the Cultural Dimensions Theory that he developed.

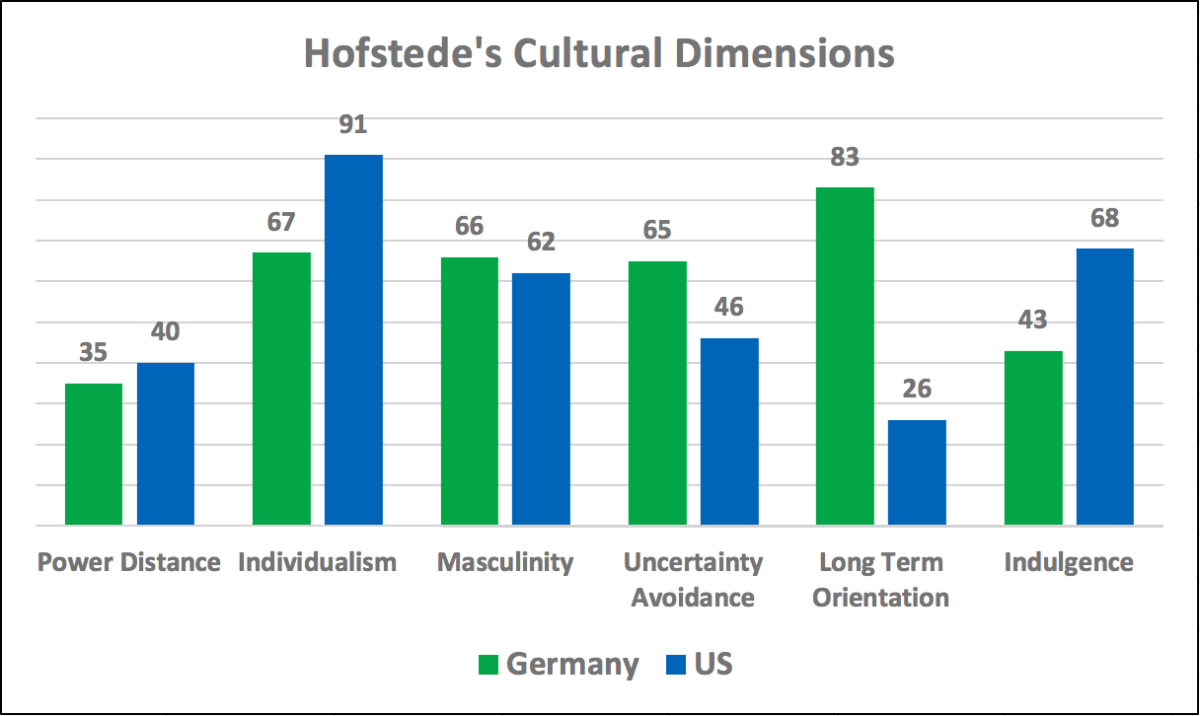

Hofstede conceptualized national cultures as manifesting along six dimensions: Power Distance, Individualism, Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculinity, Long Term Orientation, and Indulgence vs. Restraint.

Four of those dimensions – Individualism, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long Term Orientation, and Indulgence – are proving prescient in providing insights into the differences between countries that have been differently impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

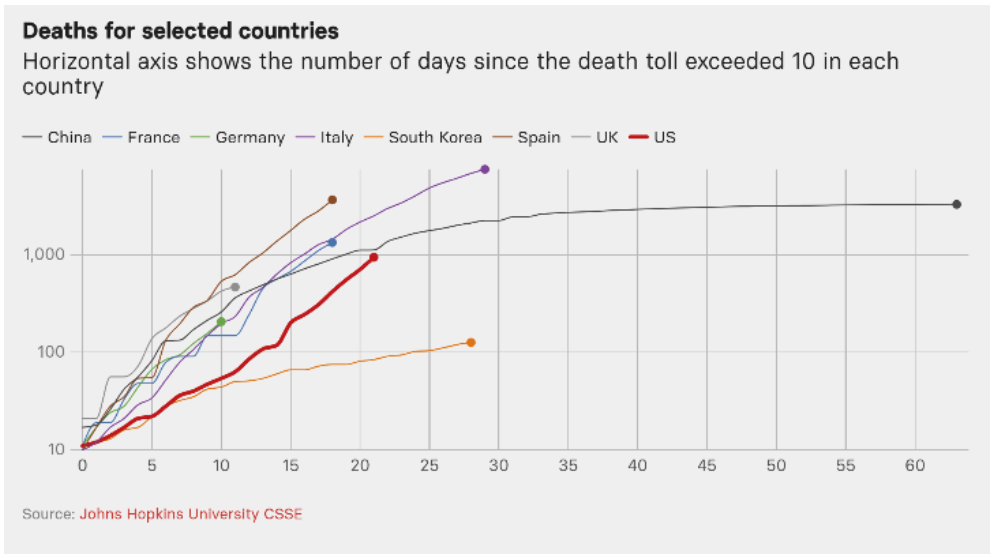

Consider the case of the United States as contrasted with Germany on these cultural dimensions – and the correspondent impact of COVID-19. As of this writing, more than 4.5% of patients worldwide – 22,327 of the 499,952 cases of coronavirus – have already died. In the US, the death rate is presently just 1.5%. But in Germany, the mortality rate from coronavirus is 0.4%; nearly one quarter that of the US. Could this be, at least in part, a vestige of who we are and how we respond culturally? Those of you who make a living from opinion research know that what, and how, people think can have a profound impact on how they act.

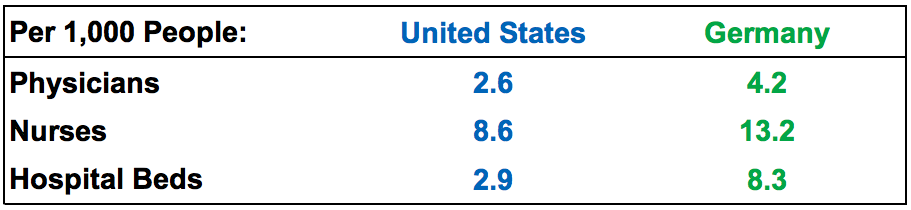

Another aspect of German culture seems to be manifest in their attitude toward healthcare, which is decidedly less driven by economic considerations than ensuring their citizens have sufficient access to resources:

Given the focus on ensuring their citizens have optimal access to care, it came as little surprise when Germany started testing even those showing relatively mild symptoms early on. Having a better handle on how many cases there were, and who was and was not infected, provided officials with a more accurate picture of the virus’s spread, allowing them to get ahead of – and flatten – the curve.

“’You cannot fight a fire blindfolded.” – WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

On March 22nd, Chancellor Angela Merkel banned gatherings of more than two people throughout all of Germany for two weeks and all non-essential businesses in the country to be closed. People are now also required to stay 1.5 meters away from each other in public. While Merkel has not yet called for a total lockdown, she has made clear that it is a card she will play if citizens fail to respect the new rules.

When viewed through this lens, the biggest differences between Germany and the US appear to be catalyzed by culture and leadership; the differences in the attitudes and actions of Angela Merkel and Donald Trump could not be more starkly clear.

It is, of course, too soon to tell if Germany will succeed as the US continues to struggle – but for now, at least, the German people – led by Angela Merkel – seem to be beating the odds.

How can researchers lend to the fight?

The entirety of the Researcher Toolkit can fit on just five shelves; four of those shelves are occupied by the collective sets of tools and techniques we use to disclose, detect, dissect, and analyze Patterns, Projections, Anomalies, and Connections.

That fifth shelf? That holds the most underappreciated, yet paradoxically perhaps the most valuable (and certainly the oldest) set of tools in the researcher’s arsenal: Story. The ability to narrate, frame, communicate, and convey through prose, pictures, and various media the insights researchers feel compelled to impart.

One of the fundamental axioms of psychology is that “perception is more important than reality.” In times of crisis, chaos, and change we look beyond formal authority to those with informational authority to help us navigate the turbulent tides. That is why, in these tempestuous times, people have gravitated toward leaders who provide demonstrably true data that helps people better weather the storm. That is why formal and informal leaders – from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, to immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci – have been so heartily embraced by the public.

Therein lies the rub – and the role researchers can, and must, play. During these times when the audiences and clients you serve are desperately seeking insights that can help them help their organizations to survive – perhaps even thrive – in the wake of COVID-19, the insights you can provide and recommendations you can make are essential.

“Insight without application is like giving a starving person a menu” – Sigmund Freud

A first step in this direction is to construct dashboards and other mechanisms that are capable of providing executives and those charged with making decisions integrated insights from a wide-range of perspectives they can act on; factual and perceptual, financial and focused on intangibles. The next step? To step up, offer guidance and advice – and make sure your expertise is being heard. Vox populi, vox dei.

1 comment

Nice