Simon Chadwick

It’s an even-numbered year, which can only mean one thing: it’s time for the ESOMAR Global Prices Study! In one of their most singular contributions to the industry, every two years ESOMAR mounts a huge exercise to collect and analyse MR prices across a range of project types from around the world. The data collection alone is an exercise of Herculean proportions: this year, 736 “bids” (i.e. priced responses to project specifications) were collected from no fewer than 119 countries. But it’s not just the scale of the data collection that fascinates, it’s the almost forensic way in which the authors of the study dig deep into the data to uncover trends and issues that otherwise may not be that obvious and which range from the interesting to the downright disturbing. This year is no different.

First, the headlines: The USA, Switzerland, France, the UK and Germany are the most expensive places to do research today. No surprises there, then. But Japan is now relatively less expensive than it once was, ranking 12th (down from 5th in 2010). Now that is a surprise, but more of that later. Prices are relatively stable, with only CATI showing consistent, but relatively mild, increases over the last four years. So far, nothing to bring us off our seats. But underneath this comparatively sanguine set of results lie some fundamental truths and issues that may indeed surprise you.

The duck may seem serene, but under the waterline it is paddling furiously. Worldwide research expenditures (new definitions of “research” notwithstanding) are either stable or gently increasing, after a few difficult years post-Great Recession. But the share taken by online research is constantly growing. According to ESOMAR’s Global Market Research Report, online methods accounted for 27% of data collection in 2012, up 5 percentage points from a year earlier. And yet the Global Prices Study reveals that Online is about 70% of the cost of CATI, which in turn is about 80% the cost of Face-to-Face. So, if Online is taking greater share and global expenditures are stable to growing, this means that the volume of research being done is growing far faster than we may be imagining. The market as measured by volume is far more robust than that measured by money.

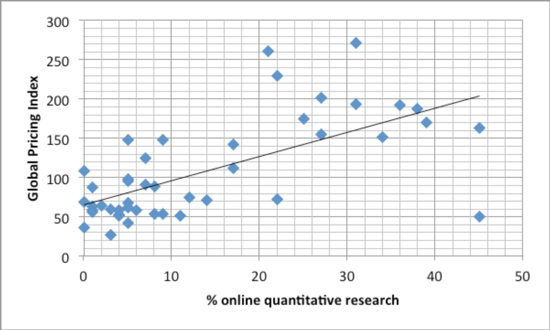

Costs may drive innovation more than we may think. In what ESOMAR calls the “Key Markets” (the top 5 in terms of size, accounting for 69% of worldwide MR expenditure), we have seen over the last few decades the relentless application of Christensen’s theory of Disruptive Technology. First CATI started to eat into Face-to-Face (F2F), then Online came along and ate into CATI. In each case, it is arguable that the new technology was not as robust as its predecessor, but it came at such a discount and was sufficiently “good enough” that it was able to succeed. We have tended to look at this as a technological phenomenon (especially where Online was concerned). But as one looks into the pricing structure of the most expensive countries in this study, it would appear that the more expensive a market becomes, the more there is an incentive for clients to look for less expensive options. As a rough and ready test of this hypothesis, I mapped countries by (a) the percentage of quantitative research carried out online and (b) their composite Global Pricing Index score as measured by this study.

The resulting picture yields an R2 of 0.425 – not stunning, but suggestive of a link. Obviously, there are a host of other factors at play here, not least Internet penetration, the overall economic well-being of any particular country as well as geographical and demographic variables. However, I would posit that it is also possible to conclude that, in markets that become inherently expensive, MR budgets are not necessarily going to increase beyond a certain point; and, when that point is reached, the incentive to look for and apply cheaper methodologies becomes that much more intense.

The greater the share of online methods, the more costly offline methods become. It would appear from the study that offline methodologies are more costly in countries where online is a predominant force. While this would seem just to be a logical continuation of the argument above (i.e. costly offline methods spur adoption of online), the interesting thing here is that these offline methods are becoming more costly in these countries. CATI in particular is an example of this, with costs rising in countries where online has established itself as a worthy competitor. Could this be a result of diminished supply of these offline methods? Certainly in the USA we have seen wholesale closure of CATI facilities and massive shrinkage in CLT capacity, leaving those still in a position to supply such services perhaps in a stronger position to firm up their prices.

Don’t be fooled by apparent price stability. A first look at the results of the 2014 study leads one to conclude that median prices for research are holding steady and indeed have been remarkably stable for the last four years. However, there are a few factors that lead one to question this: (1) the number of countries participating in the study has increased, and those that have newly “joined” are almost invariably less expensive, newer, emerging markets; (2) prices for the standardized projects on which agencies were asked to bid tend towards the mean because of structural factors in the markets being surveyed. So, for example, in the U&A study that the study ‘put out for bid’, more expensive countries in which offline methods had already largely been abandoned put in bids that were for an online execution; while cheaper countries where online had not established itself could put in bids using (relatively cheap) offline methods. Thus, any tendency to price inflation in this instance, at least, is masked by choice of methodology to overcome inherent price and structural issues in the market; (3) the number of companies providing bids for online methodologies in this study was up 75% on 2012, which means there is an inherent bias towards cheaper pricing in this study than before.

Anomalies may tell future stories. Three anomalies jumped out of the study, each of which may tell a story:

- In the US, online B2B research is more expensive than CATI. True! Yet, when you dig underneath the numbers, it appears that companies who bid only for online for this B2B project put in prices that were almost double those bid by companies who offered both options (online and CATI). Does this mean that these online-only suppliers are in a universe of their own and that, absent methodological competition, they think they can jack their prices up? Or maybe it could be symptomatic of the constrained supply of online B2B sample in the States. Time will tell.

- Online prices in Japan are absurdly low. Given the absolute dominance of online in Japan (45% of all quantitative research), does this mean that prices collapse when everybody is offering it? Or something else? Again, time will tell.

- The US is the cheapest country in the world for long-term MROCS. What? Is this because they have been doing MROCS longer than most or is there some secret we don’t yet know?

Finally, a couple of interesting tidbits that emerge from some of the questions asked in the survey – and one downright scary one. The first relates to mobile and its place in our ecosystem. For the first time, companies were asked to submit a bid for a mobile customer satisfaction study. 23 countries produced three or more bids each, amongst which were both highly developed MR nations and those which are very much in emergent mode. Of these, four were from sub-Saharan Africa. Secondly, there was ample evidence, especially in the Key Markets, that respondents are the ones who will be driving this industry to mobile, with 20% of online surveys being accessed on mobile devices and 70% of CATI calls being answered on such devices, according to the more mobile-equipped research companies responding.

And the scary finding? A frightening number of research companies do not know, or cannot define, what “nationally representative sample” means. You will want to read the full report to understand the full import of this, but all I can say is “Caveat Emptor”.

Simon Chadwick is Managing Partner at Cambiar.