Surinder Siama

First published in Research World October 2009

Noted inventor and futurologist Ray Kurzweil has a unique approach to future-gazing. And factoring in the exponential pace of technology, he can see right through to 2045.

Two movies. One book. A new university. These are just some of the things that Ray Kurzweil has been up to this year. Not to mention being a popular speaker and entrepreneur. He’s a busy man. And a man for whom life is too short.

Kurzweil speaks with a marked sense of destiny and purpose. Those movies, book and university are all part of his plan to reach where he wants to get to as safely as possible: the year 2045.

Born to invent

It all started at the age of five. That’s when Kurzweil says he caught the inventing bug. He remembers his parents giving him sets where he could build gadgets. “I can remember this feeling I had that if you could put things together in the right way, you could create a transcendent effect (although I didn’t have that vocabulary at the time!).”

A couple of years later, he built a mechanical puppet theatre where controlling the characters with strings sparked a fascination with recreating reality and human intelligence within machines.

At the age of 12 he started writing computer programmes. It’s not uncommon for teenagers to develop computer applications these days, but 50 years ago there were hardly any computers and programming languages were far less user-friendly. But, keen to try the technology, he would visit one of the “dozen computers in New York City” and use them overnight, in much the same way that Bill Gates would do eight years later. Kurzweil’s creations included a programme that analysed melodies to “find patterns in them and write melodies in the same style.” Clearly, he wasn’t your typical 12-year-old.

Several years later, he experimented with artificial intelligence (AI) programming and it was at this stage that his achievements started to gain national attention. “I got to meet President Johnson and to go on the television show I’ve Got a Secret.”

His first major invention was a reading machine for the blind and this led to other inventions. “In the course of developing that, I created the first flat-bed scanner, the first omni-font character recognition, and the first text-to-speech synthesis.” In fact, Kurzweil says that the popular speech recognition program Dragon Naturally Speaking uses his technology.

Trendspotting

Predicting the future, says Kurzweil, was a natural outgrowth from inventing. “I did start out as an inventor (and that’s principally how I see myself). I got into futurology, predicting technology trends, because of my interest in being an inventor, realising that timing was critical to being successful as an inventor. Most inventors fail not because they can’t get their gadgets to work, but because their timing is wrong.” So, for the past three decades, he has amassed and analysed copious amounts of data to model technology trends.

He discovered that you can in fact predict the future. “If you measure the underlying information properties of a technology, like the price-performance of computing, or the number of bits being moved around on the internet, or the cost of sequencing a base pair of DNA, these things are remarkably predictable.”

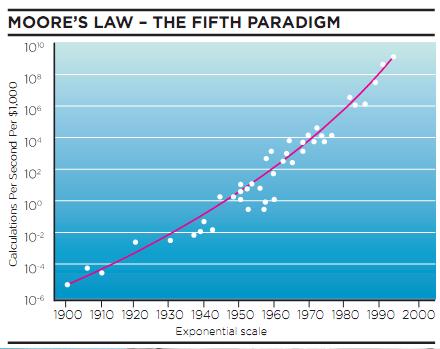

What’s more, he spotted that growth is predictably exponential. For example, Moore’s Law, named after the founder of chipmaker Intel, notes that the price-performance of computing doubles every year. Price-performance, notes Kurzweil, “is now a billion times greater than when I was an undergraduate at MIT.”

He is quick to clarify that you can’t easily predict a specific product’s likelihood of success, but you can predict the power of the underlying technologies. “Products take off when all the enabling factors for its success are in place.”

An early use of the methodology was to successfully predict the emergence of the internet. Back in the 1980s, he noticed how the ARPANET, the predecessor to the internet, was doubling in size. So he predicted that by the mid-to-late 1990s, the worldwide web would emerge as a network that connected hundreds of millions of people to each other and to vast amounts of knowledge. With hindsight, the prediction might sound obvious, but he was heavily criticised for the outlandish forecast at a time when the entire US defence budget could only afford to connect a few thousand scientists.

He seems to take this criticism in his stride. He doesn’t blame non-believers because “exponential growth is very surprising, it’s not intuitive.” And yet there are countless examples that prove it.

A recent example shows just how dramatic the pace of technology development can be. It comes from the project to decode DNA. The first genome cost around US $500 million to sequence. A Stanford University engineer has recently created technology that reduces the cost of decoding a genome by 80%, from US $250,000 to US $50,000. And the engineer predicts that it could come down to US $1,000 within a couple of years. These represent dramatic price drops/performance improvements over just a few years. According to The New York Times, “(US $1,000) is the cost, experts have long predicted, at which genome sequencing could start to become a routine part of medical practice.”

Relentless growth

What is perhaps remarkable is that the exponential pace of technology, at the root of the methodology, remains consistent over time. In fact, when he gives talks, Kurzweil shows a wonderful chart that summarises key technological developments since the late 19th century. His start point is the mechanical calculating devices used in the 1890 US Census. Plotted on a logarithmic scale, performance growth follows a straight line through to the present day.

Not even significant world events such as the World Wars or the Great Depression have dented “this very smooth, inexorable, predictable, exponential progression of computation.”

Moreover, Kurzweil says that it mirrors what is seen in biological evolution. The evolution of DNA took a billion years, and then biological evolution completely adopted it. “Then the next stage, the Cambrian explosion…went a hundred times faster.”

But there are natural limits to Moore’s Law since we cannot endlessly make chips smaller and more powerful. In fact, Kurzweil and others have predicted that Moore’s Law is unlikely to extend much beyond 2020. So, will the rate of growth finally slow? Not likely, he says, because Moore’s Law is the fifth paradigm since 1890. And each paradigm has given birth to a new one before it expires: “Every time one paradigm ran out of steam, it created research pressure to create the next.”

So what will Moore’s Law give birth to? Computing in three dimensions; “That was considered controversial when I first wrote about it in my 1999 book, The Age of Spiritual Machines. It’s now very much a mainstream notion.” Intel is already public about having prototype chips ready within a few years. The relentless growth looks set to continue.

Art of predicting

Kurzweil is used to making long-range predictions. So I ask what organisations can do to make more accurate short-term forecasts. His response is a little disappointing. “The pace of change is so fast now that predicting two to three years out is not a safe harbour anymore…that was perhaps okay, say, 15 years ago.”

But, there is some good news. As more aspects of life become what he refers to as ‘information technologies’, they start to follow the exponential growth paradigm. Take, for example, health and medicine. These never used to be information technologies. But they are becoming so as the genome is decoded. “We have software running in our bodies, that’s what these genes are, that’s tens of thousands and in some cases, millions of years old…we’ve collected the software that life runs on, the genome. We have a means of actually changing it.”

Still at an early stage, Kurzweil says that this is how drugs will increasingly be developed – on computers – when enough human code is digitised. “These technologies will be literally a million times more powerful in 20 years because they are going to double in power every year.”

With all this focus on accurate predictions, I wonder whether Kurzweil has had any flops. Adoption, he says, has sometimes taken longer than anticipated. For example, he imagined there would be many more people using speech-to-text on a PC by now. Yet people seem to be happy with using their humble keyboard for data entry. Mobile phones, however, would seem to make a more enticing platform for the technology given the inadequacy of the keyboard. The barrier is that mobiles are not yet powerful enough to run the software (mobiles, he says, are typically four-to-five years behind the PC).

The key message, says Kurzweil, is to use a little imagination when trying to predict the future. “You really need to plan your projects not for the world that you see outside your window, but for the world that will exist when you finish your project. And that will be a very different world, because the world is changing faster and faster.” After all, the printing press took 200 years to reach mass adoption, while wikis, social networks and blogs have only taken several years. “We can, and I do, make accurate predictions, at least about the underlying power of these technologies and then you need to use your imagination on what to apply these to.”

Ethical issues

2029 is the year that, Kurzweil predicts, “we will have completed the reverse engineering of the human brain.”

This is where things start to get spooky and a bit controversial. Given the ethical issues, why do it besides the fact that it can be done? Technology, he says, already makes us smarter. “We ultimately will put them in our bodies and brains to keep ourselves healthier, to integrate with our biological intelligence and make ourselves smarter, to put our brains on the internet, be able to think out in the cloud of computing.” Kurzweil is well known for wanting to significantly extend his own life, and believes that technology will develop fast enough for him to be able to accomplish this within his lifetime.

But, as researchers and marketers, wouldn’t we welcome the ability to fully understand the brain? Possibly. But 2029 will not signal the end of the researcher’s quest. Kurzweil says that while we will understand the brain by then, we will not understand every person. “It’s not only the case that our brain creates our thoughts, but our thoughts create our brain.” Everyone is different.

‘The Singularity’ is a term Kurzweil has used to refer to a point in 2045 “where we will have multiplied the intelligence of our human-machine civilisation a billion-fold by merging this non-biological version of our intelligence.” The term is used as a metaphor from physics where it is difficult to see beyond that event horizon. A time that even Kurzweil can’t predict beyond.

BT’s futurologist, Lesley Gavin, recently referred to cyborgs living among us, saying: “We are becoming more used to cyborgs in our lives. There’s already over three million in the world today, and there are probably some in the audience. People with pacemakers, for example.” We already have driverless cars at Heathrow Airport’s new terminal and the future could see robots performing surgery or fighting wars (autonomous killing machines).

These developments, which some regard with dismay as the sign of a dystopian future, throw up a host of ethical and legal issues. As such, earlier this year a group of researchers met at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in California to discuss the implications and decide on whether to impose limits on research. Limits are strongly opposed by Kurzweil as being unworkable, as it would push dangerous developments underground. He also believes they would be unjust, by denying life-saving or life-enhancing treatment to those who are suffering. Nevertheless, he does acknowledge the potential dangers inherent in these advances and has said as much in his cautionary tale, The Singularity Is Near.

This is a complex and emerging area and space does not permit a proper discussion here. However, we feature more in the accompanying podcast, including a chat with Kurzweil about Singularity University, which he co-founded with backing from Google and Nasa, and which is designed to help society cope with these changes.

Ray Kurzweil, Inventor and futurologist, he is CEO and owner of Kurzweil Technologies and author of The Singularity is Near.

Ray Kurzweil, Inventor and futurologist, he is CEO and owner of Kurzweil Technologies and author of The Singularity is Near.