This article is extracted from the 2020 Global Market Research report, where you can find detailed information on the insights industry for the world’s countries. Considered a must-have in the professional’s toolbox, this year’s edition of the Global Market Research report explores a more complete picture of the insights industry beyond the established market research and includes the tech-enabled side of data and analytics. Get the full report here (free to ESOMAR members)

The evolution and transformation of the industry has proven difficult to integrate over the years, to the point of generating an identity crisis for many seasoned professionals of the insights sector. When looked at more closely, however, these profound changes need not seem alien, nor should they appear threatening. Rather, let us see how the entire industry is sensibly interwoven, how its transformation not only supports, but even advances the profession, and why it is important to assimilate the new players and techniques created along the way.

Not just a matter of lexicon

The transformation of the insights industry has been a constantly accelerating feature for the last couple of decades. Where once upon a time you could only find a handful of companies dedicated to gathering, processing and interpreting data using established scientific protocols, nowadays the array is so wide that it has diffused its boundaries and, with them, its meaning. Even the initial designation of market research has given way to the more inclusive, yet less specific term: insights; but the truth is, that is exactly what this industry ultimately enables: the extraction of insights.

To allow insights to emerge as a final product, the industry utilises a constant, ever-evolving and ever-increasing stream of fuel, that has expanded dramatically in recent years. This fuel, data, can now be obtained from a plethora of sources and platforms, either created by or refined by, advances and refinements in technology. Often a mere by-product of a company’s main processes, data is now increasingly seen as a potentially significant revenue stream and is coveted by other companies, organisations and governments alike.

What the market research industry (and by extension, its ambassador and protector ESOMAR), realised a long time ago, was the inadequacy of simply extending the original term – “market research” – to a new set of industries whose main goal was not that of processing or interpreting data. In these cases, the label research would not apply to them. Insights, could.

By expanding the definition to include these companies in the industry’s fold, ESOMAR’s goal was to, ultimately, make them conscious of the same opportunities and derogations our sector enjoys, and entice them to make the same commitments our sector has for decades. Without data protection the industry would suffer in its credibility; without an ethics code the sector could not sustain public trust; without proper practices the reliability of the data and insights could not be guaranteed; without a community, the industry could not defend its interests and without a consistently strong element of self-regulation, our sector would no longer be able to defend the derogations it has long benefited from.

The very distinctive, tech-based nature of these companies initially made them separate players in a parallel arena. Over time, however, the line has blurred as the industry has expanded. Yet, until now, there has not been a definitive term to refer to the practices that emerged with these players while at the same time honouring the most veteran of research companies. This is a separate categorisation that we would like to offer for consideration.

This article would therefore like to propose an alternative three-way classification of the market for review and debate.

The lattice of research

So why – in this evolving world of technology-enabled data production and collection – is the categorisation of this new sector so challenging, perhaps leading to their reported reticence to adopt some of our sectoral commitments?

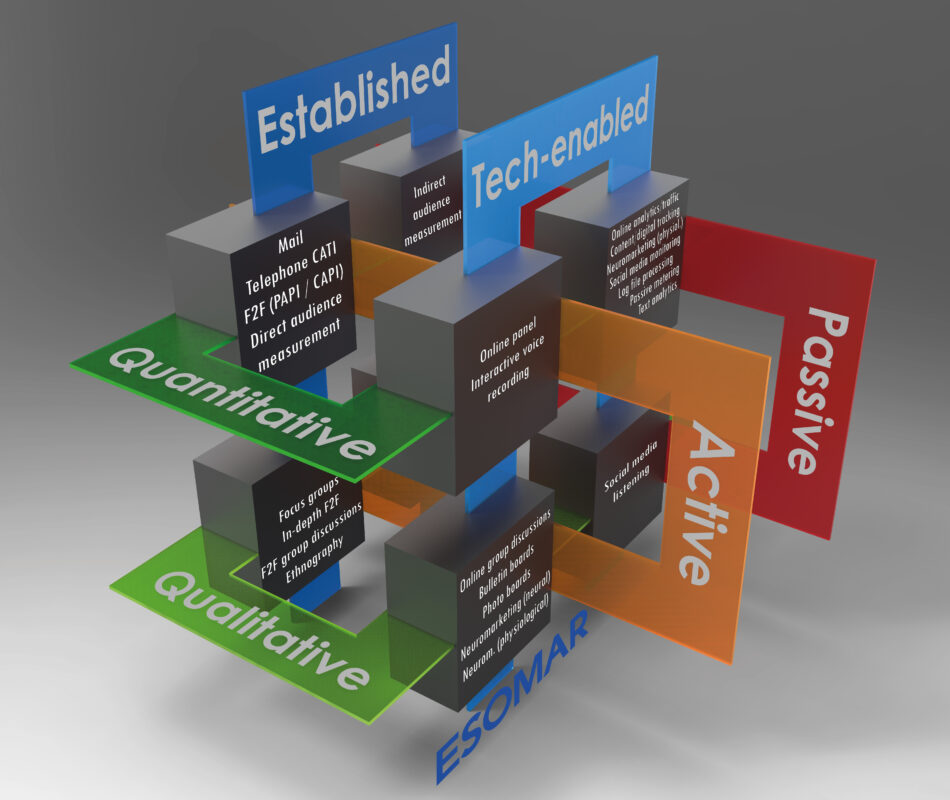

As mentioned earlier, up until quite recently the researcher had two choices; either ask as many people as possible in the shortest period of time to build a numerical dataset – quantitative research – or ask fewer people in more detail to build a clear picture of behavioural motivation or attitudinal drivers – qualitative research.

As new ways to gather data emerged which do not require a ‘real-time’, one-to-one personal interaction between researcher and respondent, methodologies have increasingly moved from being an “active” process or collection to a passive, less intrusive, less conscious (and in some people’s view, a more accurate) recording of behaviour and generation of information. Hence the differentiation between active and passive methods of research.

The most recent iteration has resulted from a wider application of technology in the industry, which has given rise to a set of methodologies that would have been impossible to apply (or conceive of) otherwise. Some of them further facilitate the unconscious monitoring of behaviour (discrete video cameras for ethnography, or cookies that track people’s computer time and surfing history), while others allow for more direct methods of measuring sub-conscious activity such as neuromarketing or eye- and face-tracking. The industry, thus, could make use of either established methods of research – long used, with a proven track record and thoroughly refined over time –, or technology-enabled (or tech-enabled) methods of research – methods that could not have existed without the advent of technology.

This three-way categorisation could aid professionals to understand the main properties inherent in each of the methods of gathering data, as well as to effectively recognise them, and the companies that offer them – both established as well as technology-enabled – as belonging to the same pool, to the same industry.

The picture coming together

This way, one could say that telephone CATI is an established quantitative active method while social media listening could be described as a tech-enabled qualitative passive one. The image below shows the three-way partition of most methods for data gathering.

The result of this more refined measure which enables us to now categorise the market according to data gathering as well as for reporting. As a result, we can now understand the different elements that constitute this US$ 90 billion industry, and track from now on the evolution of the established industry – valued in 2019 at US$ 43bn –, and the tech-enabled one – valued at US$ 47bn. The impact of having this more colourful and extended landscape can perhaps be more clearly appreciated in ESOMAR’s Global Top-50 companies of the insights industry, which includes the segments they belong to.

This more detailed definition of the industry, therefore, allows for an easier understanding of its components, helps track the methodologies that make it up – and as such, the companies specialised in them – and will allow for the easier inclusion of future changes within the profession. Perhaps more importantly, these proposed changes will help guide and frame the discussions on and around the future developments the industry is bound to experience.

ESOMAR recognises that not all elements may fully fit in their selected tri-segmentation and celebrates the evolution and complexity of the industry while it vows to continue to reassess its nature.

Source: ESOMAR’s 2020 Global Market Research report

The impact of an explicit definition

By understanding how the tech-enabled sector should be interwoven in the fabric of the insights industry, we can continue to lay the necessary foundations to accommodate it in a sensible and convincing manner, in a way that will help them recognise their own, rightful place within the insights profession, in a way that will underscore the traditional quality strengths of the sector and in a way that, ultimately, will allow us to explain the necessity of a structure and community that encourages self-regulation and corporate responsibility.

The industry should be able to properly identify all the companies which are fighting for available budgets in this rapidly changing arena. Failing to recognise all the players that present themselves as suitors to these budgets has a two-fold negative effect. Firstly, it impoverishes the industry by making its established players feel that the pie is shrinking without a possible alternative, all without realising the error of this perspective; and secondly, it ignores the myriad of companies that are moving the industry forward through unprecedented innovation, by treating them as an external threat rather than an internal strength or feature.

Let us all continue this open conversation to guide the future of the profession. A lot of work remains to be done.