Until recently, the make-up of a corporate insights team was a relatively simple affair. The large majority of staff would be trained, professional market researchers. For these people, pretty much everything revolved around the process of market research, from design to data collection to analysis and writing a (voluminous) report. Some, more senior, researchers might be possessed of a certain expertise (e.g. brand research, pricing, product testing, conjoint analysis) while others became serious category experts (pharma or automotive, for example). If you were very good and a little more ambitious than most, you might even be made a manager, responsible for a group of researchers and project managers.

In many companies, validation was the primary type of work undertaken, with 70% or more of the annual budget reserved for “rear view mirror” work – brand tracking, CSat, advertising effectiveness and so on. Even copy and product tests were mainly around validation, not innovation. And, to a large extent, this is what was being taught in business schools and MSMR programmes – indeed, scarily, it still is in some quarters.

The bottom line was that we considered ourselves professional researchers and were proud of the scientific theory underpinning the quality of our work. Nearly everything was project-based and our job was to produce data out of discrete, singular pieces of research.

Change

About 10 to 15 years ago, it started to dawn on some of us that all of this was about to change – dramatically. Initially, the change was attributed to the onslaught of technology that was beginning to enable things to be done in research that had been difficult to do before. The biggest of these at that time was the advent of the online panel, allowing for much greater volumes of research to be conducted at a much lower cost than previously. But, as we began to dig deeper below the surface, some of us also realised that change was actually beginning at the client level and that technology was more of an enabler than a force in its own right.

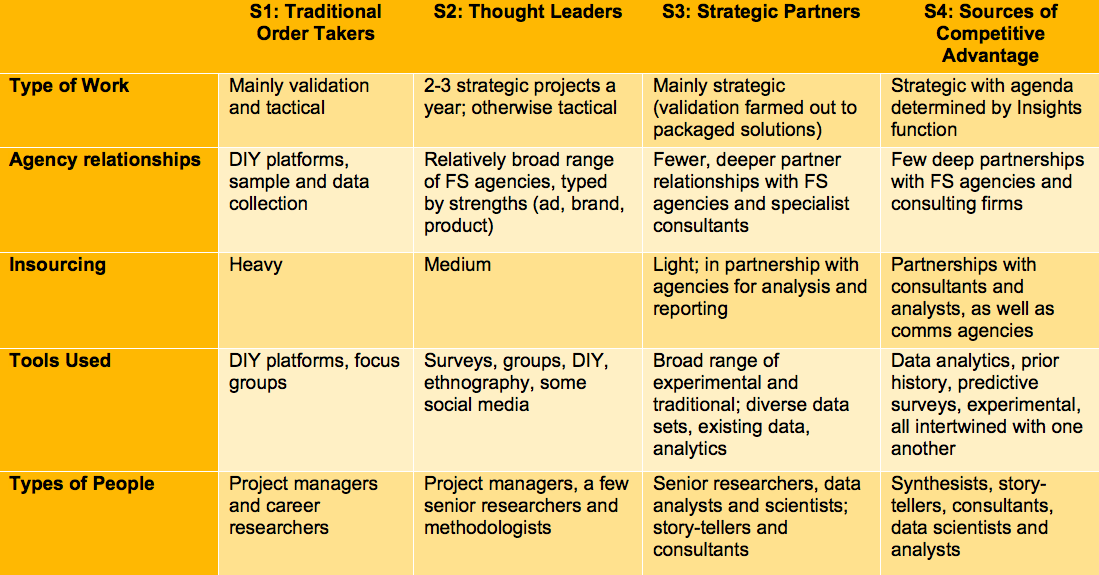

In 2006, I suggested that corporate insights functions were segmenting into six types, depending on their strategic value to the organisation and their emphasis on integrating diverse sets of data as opposed to relying on single projects. (This was later refined by BCG into their four-stage typology).

Back then, I suggested that both the existing culture and the ambitions of varying types of insights function would have major consequences for their behavior and structure. These could include:

- The types of work they chose to do

- Their relationship with full-service (FS) and other agencies

- The degree to which they insourced

- The tools they used to collect and process data

- The types of people they employed and encouraged.

Over time, these patterns did indeed emerge and became more and more dominant. Using BCG’s typology, the resulting picture today is clear:

The four types of corporate insights functions

New roles

In 2012, Ian Lewis and I hypothesised that the insights department of the future would be made up less of broad spectrum researchers and project managers and more of specialists, creative synthesists (whom we later named ‘polymaths’) and consultant story tellers who could take the story to the C-Suite with the intent of engendering action.

Specialists are needed not only because of the explosion of new tools and data sources but also because of the different sciences being applied to those data – not just statistics, but neuroscience and biometrics, behavioral economics, psychology, political science, social media and (today) artificial intelligence and machine learning. Polymaths need to be able to connect the dots, synthesising the data from divergent sources and the theories and findings of the various specialists. At the same time, departments either need to train or import compelling story-telling skills, consulting capabilities and detailed knowledge of the business to be able to influence decision-makers to take action.

Path to the future

So, seven years on, how does the landscape look now? The easiest, and most complete, answer is that all of this has been borne out, only on steroids. The trends are clear and fall into three distinct, yet overlapping, buckets:

- Talents and Skills – Many Insights functions (especially those striving to get from Stage 2 to Stage 3) are having seriously to rethink the talent make-up of their divisions. Often, this comes as a result of the organisation having declared itself to be “customer-centric” and/or “data-led”. C-Suites are demanding more and more in terms of insights leadership, especially stories and recommendations based on the analysis and synthesis of multiple data sets. As a result, there is less room for pure project management and more demand for analytics and data science skills, the ability to synthesise, and consulting skills. In a number of companies for which we have worked, this has resulted in perhaps 35% of existing staff (project managers and dyed in the wool researchers) being let go and replaced with data scientists, methodological specialists, polymaths and consultants.

- (Re)Training – It’s not enough, however, to turn over your staff and sometimes that can be dangerous. Research (even when dealing with new areas such as social media or analytics algorithms) still needs to retain deep knowledge of the basic principles – you can’t shepherd all researchers out the door. But maybe you can train them in the softer skills of the role – how to be a consultant, how to influence people, how to communicate and tell compelling stories. An entire new industry has been born to try and instill these skills into existing Insights departments.

- Remapping – In the intervening years, technology has progressed at a rate that no-one back then could have predicted. As a result, we are now able to process quantities of data far exceeding our then imaginings; manipulate it to a greater extent in terms of its predictive powers; and do all of this no matter in what format or where it exists. This has led some managements to believe more in the power of existing data than in that of new primary data, accelerating the move to analytics and data scientists and, in some companies, throwing into confusion the role of market research entirely.

To be the head of insights in a major corporation today is therefore both a daunting and yet exhilarating challenge. The demands in terms of your effect on the business combined with major disruption to your business model (and indeed your primacy as generator and curator of insights) means that you are constantly having to rethink the talent that you have vs. the talent that you need, how and what you train them for, and how you interact with everyone else who claims to be a source of “insight”.

Truly, heads of consumer insights in today’s corporations are this generation’s unsung heroes.