Loss aversion is a cognitive bias which describes the way in which we feel the pain of a loss more than the pleasure of an equal gain. This means that we value more highly what we already have than that which we stand to gain.

But why do people do this…

To agree to a gamble with a 50-50 chance of winning or losing, generally speaking, previous research has suggested that most people would need to gain twice as much as they stand to lose. For instance, most people would need to be offered at least £20 in order to gamble on a coin toss where they could lose £10.

Few are immune to this emotional response. Andre Agassi, the US tennis star once commented:

“A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad.”

“A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad.”

During a match or a race, athletes sometimes perform better when they are trying to avoid losing points or have been underperforming, than if their efforts will simply strengthen their lead. For example, golfers are often more focused when putting for par [this is the predetermined number of strokes that a top golfer should require to complete a hole] to avoid a loss. Research analysing 2.5 million putts in the PGA tour found that professional golfers make par putts (thus avoiding dropping a shot) more often than birdie putts (one shot better than hole par).

Here’s Tiger Woods on this:

“Any time you make big par putts, I think it’s more important to make those than birdie putts. You don’t ever want to drop a shot. The psychological difference between dropping a shot and making a birdie, I just think it’s bigger to make a par putt.” [1]

What might this mean for the top 20 professional golfers?

Well, their score would improve by more than one stroke per tournament and, on average they would earn 17.6% more, roughly an additional $640,000 more per year from PGA earnings. This does not include additional income from endorsements and commercial sponsorship.

While most of us are not top athletes, there are undoubtedly everyday occasions and activities where we might be missing out on significant benefits because of loss aversion! For example, we might be reluctant to sell our losing stocks and shares. It also helps to explain why it’s psychologically easier to pay for things on a card than it is using cash. We must physically part with cash whereas a card comes back to us intact and unrecognisably different.

We may also end up making poor decisions due to loss aversion. Consider these two scenarios:

Threatened by a superior enemy force, the general faces a dilemma. His soldiers will be caught in an ambush in which 600 of them will die unless he leads them to safety by one of two available routes. If he takes the first route, 200 soldiers will be saved. If he takes the second, there’s a one-third chance that 600 soldiers will be saved and a two-thirds chance that none will be saved. Which route should he take?

Most people think the general is better to take the first route, reasoning that it’s better to save the lives that can be saved. But what about this situation:

The general again has to choose between two escape routes. If he takes the first, 400 soldiers will die. If he takes the second, there’s a one-third chance that no soldiers will die, and a two-thirds chance that 600 soldiers will die. Which route should he take?

Most people choose the second route, yet the outcomes are identical. Our decisions differ simply because the potential loss is much more salient in the second scenario.

These were taken from a 1985 article in Discover magazine by Kevin McKean on Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s.

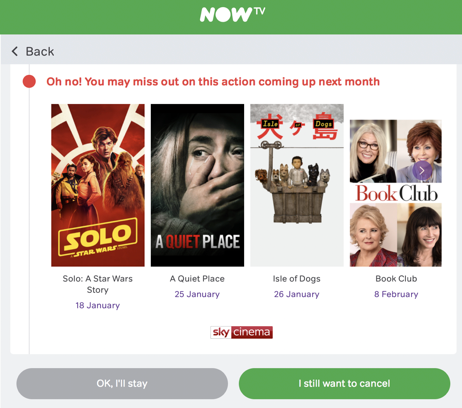

Loss aversion is used by many companies all around us both in marketing and research:

In research, we often use types of deprivation to trigger loss version and surface those deep subconscious brand values or associations. And if you look around you will see some great uses of loss aversion such as these two below:

So how we frame choices and decisions to people can end up having bigger effects on their consequent decisions and behaviour than we might think!

NEXT IN THE

SERIES: Every three weeks The Behavioural Architects will put

another cognitive bias or behavioural economics concept under the spotlight.

Our next article features the concept of reciprocity.

www.thebearchitects.com

@thebearchitects

PREVIOUS ARTICLES IN THE SERIES:

System 1 & 2

Heuristics

Optimism bias

Availability bias

Inattentional blindness

Change blindness

Anchoring

Framing

[1] Source: Pope, D.G., and Schweitzer, M.E. “Is Tiger Woods Loss averse? Persistent bias in the face of experience, competition, and high stakes AER 101 (Feb 2011): 129-157