By Crawford Hollingworth and Liz Barker

The Optimism Bias describes our tendency to predict the future with rose-tinted spectacles, in that we overestimate our likelihood of experiencing good life events and underestimate the likelihood of suffering negative events. More simply, people think they’ll be luckier than they are likely to be. Neuroscientists estimate that around 80% of us are affected by optimism bias to some degree.

But why are people so optimistic?

A clue to the underlying problem can be found in another study. This found that asking people either for their predictions based on realistic “best guess” scenarios; or for their hoped-for “best case” scenarios produced indistinguishable results! Our tendency to be optimistic however, is thought to help motivate us and protect our mental health. Unless we are extremely optimistic – when we may make dangerous choices – a little bit of optimism can help us to get through life.

This was illustrated cleverly in a recent collaboration between Prudential and Dan Gilbert, a Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. They conducted a fascinating experiment called ‘The Optimism Challenge’. People were asked to recall and rate how positive or negative events of great significance in their past were – and the same for anticipated future events.

This simple exercise revealed our tendency toward unrealistic optimism: whilst around 60% of events in people’s past tended to be positive, they believed the future would fare much better, with over 80% of events being positive (see image below). We might be lucky enough to experience a turn of good fortune, but it’s likely we’ll still get our fair share of bad things happening to us!

Source: Prudential

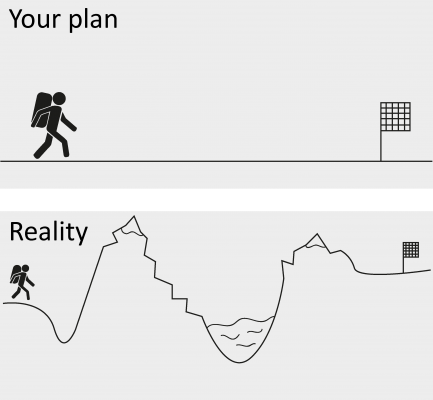

Related to optimism bias is the planning fallacy. This is a tendency for people and organisations to underestimate how long they will need to complete a task. Researchers investigating the fallacy found that when students were asked by what date they were 99% certain they would finish their project, only 45% actually finished by the date they had suggested.

And it’s not just students who are susceptible…..

- Denver’s new International Airportopened 16 months late, with a final cost of $4.9 billion, at a cost overrun of $2 billion (with some estimates as high as $3.1 billion over budget)

- The Eurofighter Typhoon, a joint defence project of several European countries, was delivered over four years late at a cost of £19 billion instead of £7 billion

- The Sydney Opera House may be the most legendary construction overrun of all time, originally estimated to be completed in 1963 for $7 million, and finally completed 10 years later in 1973 for $102 million.

However, there are strategies to minimise susceptibility to the planning fallacy…..

Knowing that hosting the Olympic games typically comes in way over budget, the UK Treasury insisted that the budget for the London 2012 games be revised to include a £2.8 billion contingency fund. They calculated this by a formula that recommended including contingencies for 60% of the original budget to adjust for unrealistic optimism. The result was that the final bill for the London Olympics totalled £8.92 billion, an impressive £377 million under the original estimated budget of £9.28 billion. This meant that there was some money left over at the end, making London 2012 the first Olympics ever to cost less than expected.

So what does this all mean?

Whilst we should always take optimism into account, especially when planning, remember that it does enhance our lives in many different ways – it feeds the fun of anticipation and motivates us to keep pursuing a goal because we believe we can achieve it. Without it, life would be quite miserable!

Next in the series..

In three weeks, The Behavioural Architects will put another cognitive bias or behavioural science concept under the spotlight. The next concept under the spotlight will be Availability Bias.

By Crawford Hollingworth and Liz Barker, The Behavioural Architects

Crawford Hollingworth is co-Founder of The Behavioural Architects – an award-winning global insight, research and consultancy business with behavioural science at its core, which he launched in 2011 with co-Founders Sian Davies and Sarah Davies.

Liz Barker is Global Head of BE Intelligence & Networks at The Behavioural Architects.

@thebearchitects

PREVIOUS ARTICLES IN THE SERIES: