We have a common tendency to adopt the opinions and follow the behaviours of the majority to feel safer, avoid conflict or simply to be more cognitively efficient in our decision-making.

But why do people do this?

To recap on our last Bias in the Spotlight column, social scientists have identified two types of social norms:

- Descriptive social norms – doing what everyone else is doing e.g. buying the latest iPhone that everyone seems to be getting

- Injunctive social norms – what others believe or what others approve of and therefore what we know we should be doing e.g. tipping a waiter is a cultural norm

In our previous article we looked at how injunctive and descriptive social norms nudged people to pay overdue taxes. Yet social norms can be used in multiple contexts, not just citizen compliance. So in this article, we look at another context; how both types of norms can encourage doctors to prescribe fewer inappropriate antibiotics.

Social Norms Illustrated

University of Southern California researchers tested several interventions on primary care physicians in 49 practices in Boston and L.A., based around socially motivated behaviours[i]. Two of these interventions were astoundingly successful. They reduced prescription rates by around 16 – 18 percentage points. The lead researcher on the study, Jason Doctor, says:

“It turns out doctors are humans too; just like others, they respond to the social cues that others do.”

The two successful interventions were:

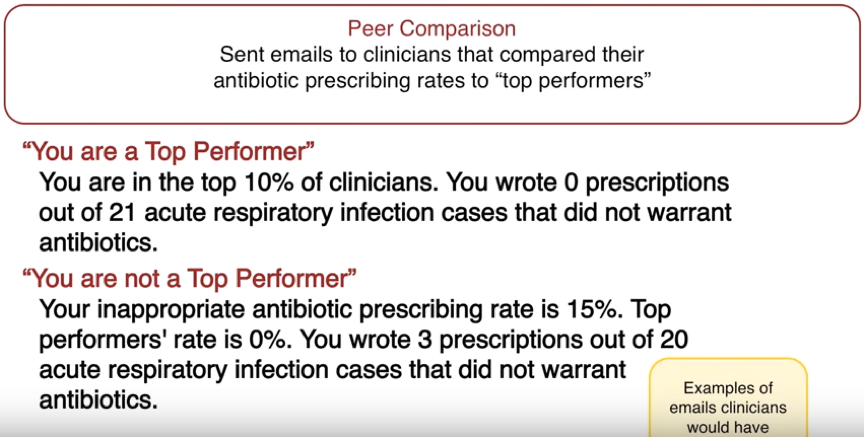

1. Peer comparison and descriptive social norms

Doctors in this intervention received an email informing them of their individual antibiotic prescription rate, and their ranking in the clinic from highest to lowest for inappropriate prescribing; their so-called ‘performance ranking’.

- Doctors with the lowest prescription rates were told they were a ‘top performer’ and received a ‘Congratulations’ message

- Doctors with poorer performance received an email with a count of their inappropriate antibiotic prescribing (see image)

This intervention made clever use of descriptive social norms – what other doctors are doing. This realigned doctors’ misperceptions of prescription rate norms and practices. There is also a strong element of ‘big brother’, making doctors fully aware their prescription patterns are being observed. It is important to note here that while the ‘big brother’ effect was successful in nudging doctors to reduce unnecessary prescriptions, it must be applied with care.

A ‘big brother’ effect can sometimes have negative influences on behaviour (e.g. reduced trust, feelings of insecurity and stress) and so the specific context and desired behaviour change must be considered before blindly utilising it.

This intervention led to a 16 percentage point reduction (from 20% down to 4%) in antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratoryinfections by these doctors.

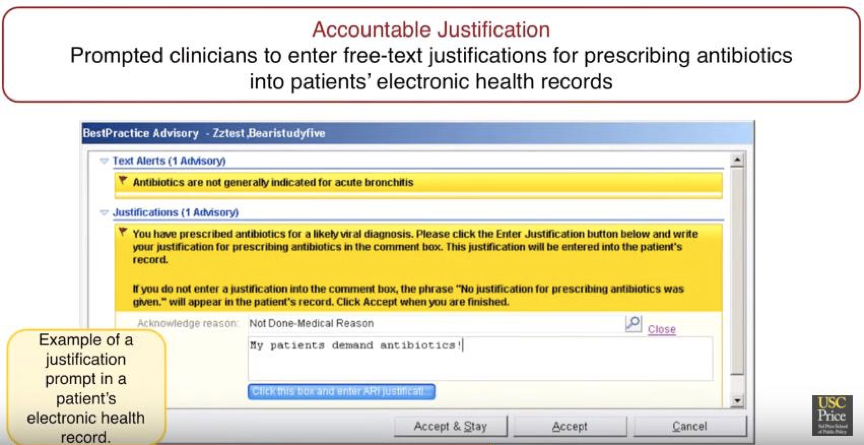

2. Accountable justification using injunctive social norms

In this intervention, if a doctor began to register an antibiotic prescription for a patient in their electronic file, an automatic prompt would appear on screen, asking the doctor to note down the reasons why antibiotics were justified in this case (see image).

This written note would then be recorded in the patient’s file, and would be accessible for other doctors and healthcare professionals to see. However, the doctor could also change their mind and cancel the prescription.

The prompt likely made injunctive social norms (practices doctors knew they should be doing), and professional conduct far more salient in a timely manner. This perhaps made it easier to resist pressure from their patient to be prescribed antibiotics. Such pressure is thought to be one of the main drivers of inappropriate prescribing due to patient ignorance of when antibiotics are, and are not, effective.

The prospect of a written record also likely enhanced this social effect, as doctors realised their justification (or lack of one) would be on their file for others to see and record.

This intervention led to an 18 percentage point reduction in antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections by doctors, from 23% to 5%.

So what does this all mean?

Knowing what others are doing or being reminded of what is approved of in society can be influential. When applying social norms messaging in communications though, subtle differences in the context can mean one message could be more effective than another.

Therefore, it can be useful to do two things:

- Conduct in-context consumer research to help find the angles that might increase the effectiveness of a message

- Test several variations to see what works best.

NEXT IN THE SERIES: Every three weeks The Behavioural Architects will put another cognitive bias or behavioural economics concept under the spotlight. Our next article features Commitment bias.

www.thebearchitects.com

@thebearchitects

PREVIOUS ARTICLES IN THE SERIES:

System 1 & 2

Heuristics

Optimism bias

Availability bias

Inattentional blindness

Change blindness

Anchoring

Confirmation Bias

Framing

Loss aversion

Reciprocity

Hot cold empathy gaps

Social norms part 1

[i] Persell, SD, Doctor, JN, Friedberg, MW, Meeker, D, Friesema, E, Cooper, A, Haryani, A, Gregory, DL, Fox, CR, Goldstein, NJ & Linder, JA 2016, ‘Behavioral interventions to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing: A randomized pilot trial’, BMC Infectious Diseases, vol. 16, no. 1, 373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1715-8