Wiemer is the editor of the book ‘Eat Your Greens’. The book is a collection of papers from marketing’s leading thinkers: Mark Ritson, Richard Shotton, Phil Barden and Byron Sharp to name a few. The scale of collaboration involved to amass contributions from some of marketing’s foremost – and one would assume busiest – practitioners, is an achievement in and of itself.

‘Eat your greens’ is an English idiom which encourages people to eat vegetables. Eating vegetables promotes long term health, growth and reduces the risk of illness. Here, Wiemer and his fellow contributors promote evidence-based thinking as a diet that grows brands and improves commercial performance.

A variety of marketing vegetables

Eat Your Greens is distinctive for its breadth of perspectives. Marketing is challenging and as Richard Shotton identifies in The Choice Factory, marketers are often overconfident which can restrict marketer’s desire and ability to educate themselves. Wiemer describes this more directly as: “people being too busy and lazy”.

He set an ambitious objective for Eat Your Greens: to present marketers with knowledge from fields outside of their own speciality. And the book delivers in 42 short chapters from 38 authors. Each has its own story, style and perspective – a structure which keeps your attention whilst helpfully making it easy to put down and easily pick it up later without feeling lost.

All the marketing vegetables in Eat Your Greens, are combined by one uniting quality: their use of evidence to debunk myths and misconceptions about consumers and how we influence them (or not). But also to offer perspectives on how marketing can better itself so we can effectively sell more, for more.

Greens for commercial performance

Wiemer’s hunger for evidence stems from realising that his earlier work in management consulting didn’t always support commercial results. He sees the role of evidence as the challenge to link what marketing does to profit and growth. Wiemer is quick to state that evidence-based marketing’s fundamentals were developed 60+ years ago. The measures of commercial results – sales and profit – haven’t changed in the last 60 years. Consequently, it’s reasonable to think that what drives these results is largely the same. Unfortunately, many current popular marketing practices are often tangential, abundant with spurious results and therefore often nothing more than an unhelpful distraction.

And then there’s the difference between facts and evidence, which isn’t just semantic. Wiemer summarises the difference:“You can measure the life out of anything. And that will certainly generate a lot of data. But without correct interpretation in context that data will be of little value. The value lies in facts which fit replicable patterns.”

Wiemer’s statement couldn’t be more pertinent. Marketers now operate in a time where more than ever, everything is measurable but this change is centred on the web where we measure lots of activity and connections but still aren’t very clear about the connection to business or communications performance. But what’s the point in measuring likes, shares, click-through-rates etc. if they can’t be linked to commercial performance? Measures that aren’t linked to commercial performance can be harmful for instance draining the attention of time-poor decision makers in irrelevant data to, at worst, giving inaccurate estimates regarding a brand’s growth.

A vegetable diet with a fruity core

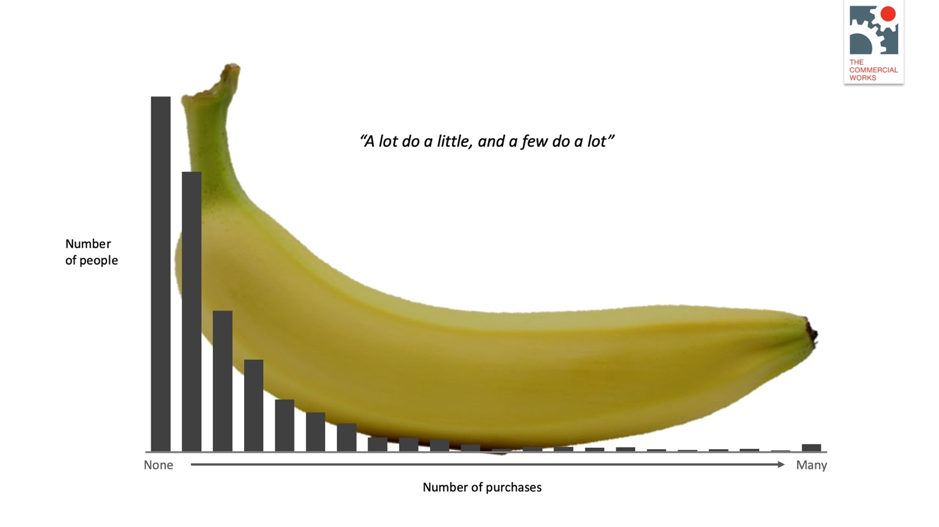

Although Eat Your Greens is an idiom based on vegetables, Wiemer uses a banana to start us thinking about how brands can improve commercial performance.

Let me explain.

The example below demonstrates that a brand’s customer base is mostly made up of light buyers. For instance, in many CPG categories most of a brand’s customers buy it only once per year, or even much less frequently. Conversely, brands have very few frequent buyers. For many brands, often may be once a month or less. The resultant banana-shaped distribution this creates is a Negative Binomial Distribution (NBD), so called for the inverse relationship between the number of buyers and their frequency or weight of purchase. This pattern is seen in high frequency categories like packaged food, beverages, household and personal care. In categories such as financial services or durables, where purchase cycles are longer, one needs to allow for more time to uncover this pattern. The NBD is one of the fundamentals of brand growth and was first identified by Andrew Ehrenberg in 1957 and found time and again everywhere. Wiemer simply uses the banana analogy to make that finding more memorable.

However, despite the evidence that NBD exists nearly everywhere, researchers and marketers are fixated with identifying and targeting unique, influential or highly loyal buyers because they were told to in their marketing text-books which are filled more with case studies than fact-based evidence. This is despite such buyer groups being a small proportion of a brand’s customer base. As Wiemer bluntly states: “It doesn’t make sense to put all your money and effort into targeting a group of people that will always remain a very small group of people.”

It doesn’t make sense to put all your money and effort into targeting a group of people that will always remain a very small group of people.

This is supported by recent research too. At Cannes in June 2019, WARC released a report entitled Anatomy of Effectiveness. This report supports Ehrenberg’s finding and Wiemer’s efforts to publicise it. WARC place reach as being at the heart of advertising effectiveness. This infers that the greater advertising’s reach, the more light buyers it can influence. The more light buyers advertising can influence, the greater volume of selling opportunities it can create.

Research – The vegetable hotpot

As WARC often demonstrate, research can – and should be – vital to evidence-based marketing. However, research can only be vital if 1) it measures the correct things and 2) looks at data in the correct context.

The ‘correct things’ to measure are metrics that are linked to buying behaviour and therefore, linked to commercial growth. Wiemer identifies three questions researchers should ask to ensure research measures are ‘correct’:

- Does this drive commercial results?

- Is there a pattern?

- Are our results normal?

To create context for looking at data, Wiemer strongly advocates using norms. Norms allow you to understand if what data is showing should be expected or not. We can therefore understand if data is truly delivering ‘new news’. Researchers and marketers’ obsession with ‘new news’ draws words of warning from Wiemer: “Everyone is obsessed with finding things that change or move. And as humans we like novelty and excitement. This means people often exaggerate the importance of small changes in metrics. However, when the little changes people see were tested against norms, we’d see many of these changes as being expected or within expectable sample variation. But because norms are under-used, people can draw the wrong conclusions.”

But businesses are impatient and largely manage to short horizons whereas consumer behaviour changes slowly or not at all, which is why brand tracking can often take several years to show changes in fundamentals of choice that affect the brand.

Peter Field provides a lovely analogy in Eat Your Greens when he discusses how the number of campaigns with short-term objectives are increasing at an industrial scale, and are killing effectiveness. Like fireworks, these campaigns produce a lot of fire and noise, but fail to leave a lasting impression. Wiemer adds: “And leaving a lasting impression is of course crucial for those who buy you (very) infrequently. But these people truly are marketing’s Forgotten Majority.”

Presenting relevantly and simply

The effective communication of research and evidence is essential for it to create value for a business. Central to this is placing research and evidence within a commercial context, which is what makes it relevant – or really matter. Wiemer encourages researchers to get clients to divulge their full commercial reality to them. Even if asking for this information is uncomfortable. Often, Wiemer believes, it’s the uncomfortable questions and answers that best drive progress. Simply having a client look at a report to ‘add’ commercial context isn’t enough. Research needs to be immersed in commercial context throughout.

Much like Wiemer advocates the laws of business fundamentals in gathering evidence, he suggests some basic rules to simplify communicating research and evidence:

- Get your audience to focus on a small number of simple things that the business needs to know

- Make it clear how everything you’re communicating links business results

- Communicate with simple language

In explaining this, Wiemer summarises the need for succinctness: “Deliver on the drivers”.

I’ve eaten my greens and can testify that they’re intellectually delicious. The thousands who have also picked up the book will likely concur. Now there’s evidence; it’s a worthwhile read. I suggest you pay the vegetable aisle a visit, you will surely benefit from it.