200 105 390 8.

Believe it or not, these four little numbers go a long way to explaining our industry’s trajectory today. The first two (measured in millions of Euros) are, respectively, the revenues and sale price of the four custom research divisions sold by GfK to Ipsos recently. The latter two, measured in US Dollars, represent the same for the sale of Qualtrics to SAP – except that the last digit represents billions. A classic MR business with revenues half of those of Qualtrics gets sold for a price that is 2.5% of that obtained for a MR/CX platform. What’s more, the GfK businesses were profitable and Qualtrics barely breaks even. Now SurveyMonkey has joined the fray by acquiring Usabilla, a UX/CX platform on a valuation that far exceeds the company’s actual performance.

What this, combined with the billions invested in the marketing analytics industry, the breathless commentary of a number of pundits, and the interminable discussion around AI and Machine Learning, all appears to say is that marketing and business insights going forward will be a technology-driven industry and that the human element of what makes us so valuable to businesses and other organisations will become increasingly unimportant.

In case you think I am indulging in an advanced age hissy fit of hysteria, let me quote two people who should know better. The first, an executive in the industry, opined recently that AI was a great thing for research as it would dramatically reduce room for error. He would have done well to speak with a client of mine who noticed the error rate in his data coming out of a panel company increase from 6% to 23%. The reason? They had switched to AI-powered sampling. The second, the Data Editor of The Economist, opined in the pages of Research World some time back that the era of correlation was dead and the era of causality had arrived. What tosh! Aim AI at any old data set and the odds of it coming back with a spurious correlation are actually quite high.

Three paths to insights

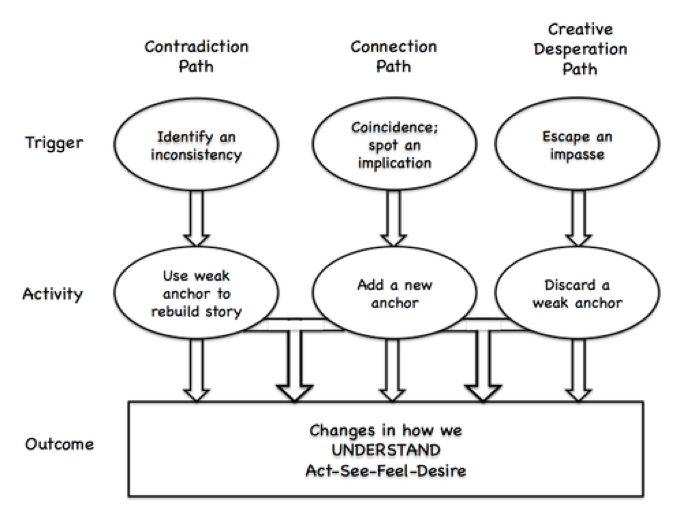

To bastardise a quote from Spiro Agnew, the “nattering nabobs” of causality completely miss the fact that the best tool for understanding the human being is the human brain. A blind faith in data and machines ignores the way in which we, as researchers, very often arrive at insights. One construct that is put forth by Gary Klein [1] posits three paths to insights: Connection (which is the path that most of us believe in), Creative Desperation (the Sherlock Holmes approach), and Contradiction.

This last is the most likely to confuse a machine and yet is one of the most valuable ways of arriving at insights. Take the example of another client of mine that had completed an A&U for a food manufacturer, the results of which pointed to unremitting doom for one of their brands. The analysts involved, however, spotted one complete contradiction in the data set. Having checked that the data were in fact OK, they started to ask themselves “where else can we look?” to explain this contradiction. And so they started down a path of looking for other data sets that could shed light on the values as well as the habits of the population that seemed to be behind the contradiction. Lo and behold, insights began to emerge that suggested an entirely different strategy for the client, a strategy that yielded a market leading position within one year. It took the human brain, human curiosity and the ability to be comfortable with contradictions to get to this point. I am not sure that a machine could (yet) do that.

True synthesis

Machine Learning enthusiasts point out that machines are a lot faster and more facile at synthesising diverse data sets than we are. In a strict sense that may be true – the ability to churn through enormous amounts of data and suggest outcomes is indeed one ML’s biggest advantages. But true synthesis – the ability to connect dots that do not at first look to be connectable – lies in the ability to bring different ways of thinking to solving a particular problem.

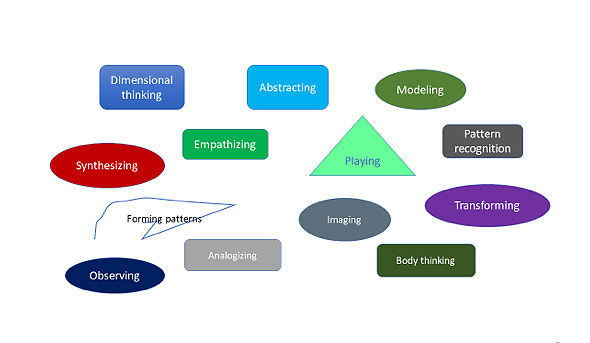

There are thirteen common patterns to thinking [2]. The most successful synthesis involves collaboration among people who bring as many of these thinking patterns to the party as is possible.

Successful insights generation (both in quality and quantity) therefore rests not only on the explicit data that we have in front of us but also on the ways in which we think about those data and how we form patterns with it. But, more than this, it also relies on implicit or tacit knowledge – the ability to recognize parallels, to draw from knowledge that we have internalised and yet find difficult to express or socialise. It’s the way doctors work as well as car mechanics, fire fighters, detectives and so many other professions.

For example, another client of mine who specialises in the food industry realised a few years ago (before it was really manifest in shopping behavior) that there was a set of values abroad that was growing around “cleanliness” of food labeling. Increasingly, people were looking at ingredients labels on foods in the search for those that had the fewest and most natural ingredients. He formed an online community to study people who were forming deep-set beliefs in this area. Projecting forward into parallel categories, he then realised that it was likely that Clean Label would spread into alcohol, juices, personal hygiene, cosmetics and even clothing. He was relying not only on direct evidence but his own tacit knowledge and his ability to project “outside the data”. Those clients that listened to him are reaping the benefits in terms of growth and financial performance that were unimaginable to them just five years ago.

Understanding changes in value systems and deep-set beliefs allow us as researchers to get out ahead of the trend based on our understanding of human nature, not just behavior as it is today. So let’s not get carried away by the flashing lights of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. They will both be incredibly useful and will help us enormously both operationally and in our ability to understand larger and larger data sets. But they will not replace the ability of the human brain, human collaboration, human curiosity and the capacity to accept ambiguity and contradiction as pointers to insight.

As a very wise boss once said to me, “Simon, never underestimate the power of ambiguity”.

[1] G. Klein. Seeing What Others Don’t: The Remarkable Ways We Gain Insights

[2] M. Root Bernstein, Spark of Genius: The Thirteen Thinking Tools of The World’s Most Creative People (2002)

1 comment

Nice article and wisely said, Simon: “The best tool for understanding the human being is the human brain.”